Anti-Asian Hate: It’s Time To Stop Playing “Chinatown, My Chinatown”

Three days after the July 4th mass shooting in Chicago I woke up to a piece of news on the homepage of the World Journal, the largest Chinese-language newspaper in the United States. An elderly Korean American man in Flushing, Queens, was approached and shoved at a gas station by a man he did not know, who shouted, “I hate Chinese!” When the attending police officer learned the man was not physically injured, he advised him to let it go. “You just had a bad day.” The old man replied, “Isn’t there a nationwide problem with hate against Asians? I don’t want this person to take to the streets and continue to hurt others.” The NYPD filed a case, but recorded it merely as a violation, noting that there was no injury. Only physical injuries fall under New York’s hate crime statute. Other abuses—punching, slapping, spitting—do not qualify.

Anti-Asian hate violence has been regular news in the World Journal over the past two years. Whether it be monstrous or minor, incurs physical harm, death or not, the frequency of such stories mirrors both the rampancy of Asian hate crimes in the United States and the high anxiety of the Asian American community. As the journalist Kristie-Valerie Hoang observes, “Anti-Asian violence is part of an epidemic of racism.” Many anti-Asian incidents, however, receive little notice or are simply under-reported. The Asian American Bar Association of New York reported that just 7 out of the 233 anti-Asian attacks during 2021 led to hate crime convictions. Though many anti-Asian attacks are far more serious than what this man endured in Flushing, his story got to me. It’s the banality, the normalcy, the everydayness of it. More often than not, anti-Asian crimes are invisible.

The invisibility of anti-Asian racism is a reflection of the historical invisibility of Asians themselves in the U.S. cultural imagination. In K-12 school curricula Asian American history has been largely absent until recently. At universities, researchers and courses on the subject of race in America often exclude Asian Americans as a topic of study. As the sociologist Jennifer Lee notes, “When we make the choice—and it is a choice—not to include Asian Americans in our research, we must ask ourselves what are we missing?” In colleges, this historical racial invisibilization is frequently perpetuated in textbooks, such as America’s Musical Life: A History (2001), and course offerings.

In order to understand and address the rampancy of anti-Asian racism and violence, it is necessary to understand and teach the difficult past of Asians in America and confront its historical invisibility.

Actress Cheet Sing Mui as a woman warrior, by May’s Photo Studio in San Francisco. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

American music has been fundamentally shaped by its transpacific history, and this history must be included in our curricula, research, concert programming, and discussions of race and American music. The transpacific history of American music began in the early 1850s, shortly after California acquired its statehood. Attracted by the discovery of gold, immigrants from the Pacific Rim region arrived in large numbers and partook in the nation-building of the United States and the development of its modernity, such as constructing the transcontinental railroad. Pacific-rim immigrants brought their skills and customs, as well as their musical practices. A full-fledged Chinese opera troupe staged its first performance in San Francisco in 1852, just a year after the city’s first full staging of a European opera. In 1869 in Marysville, a city bustling due to mining and railroad construction, an Italian opera troupe was turned away from the city’s only theater when a Chinese opera troupe engaged the venue for months, owing to their overwhelming popularity.

Actresses and actor in a Garden Scene, by May’s Photo Studio in San Francisco. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Throughout the gold rush era, the building of the continental railroad, the Reconstruction era, and the rest of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese opera theaters continued to thrive. Countless Chinese theaters opened across the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta area and Sierra Nevada foothills. By 1880, four Chinese theaters had been built in San Francisco, in sizes comparable to the city’s top theatrical venues, such as the Metropolitan Theater. Even as Chinese immigrants, soon after their first arrival, suffered from racial hostility and violence and faced anti-Chinese legislation from local to state and federal levels, Chinese theaters continued to prosper through the end of the nineteenth century, and had a second golden era in the 1920s with more than ten Chinese theaters in North America.

Just as we need to acknowledge and learn about the accomplishments of Chinese railroad workers in the nineteenth century and California’s indebtedness to Asian immigrants for its precipitous growth in that century, we need to subscribe to the transpacific history of American music as American music studies’ own subject matter. And, it constituted a significant part of the early Asian American experience.

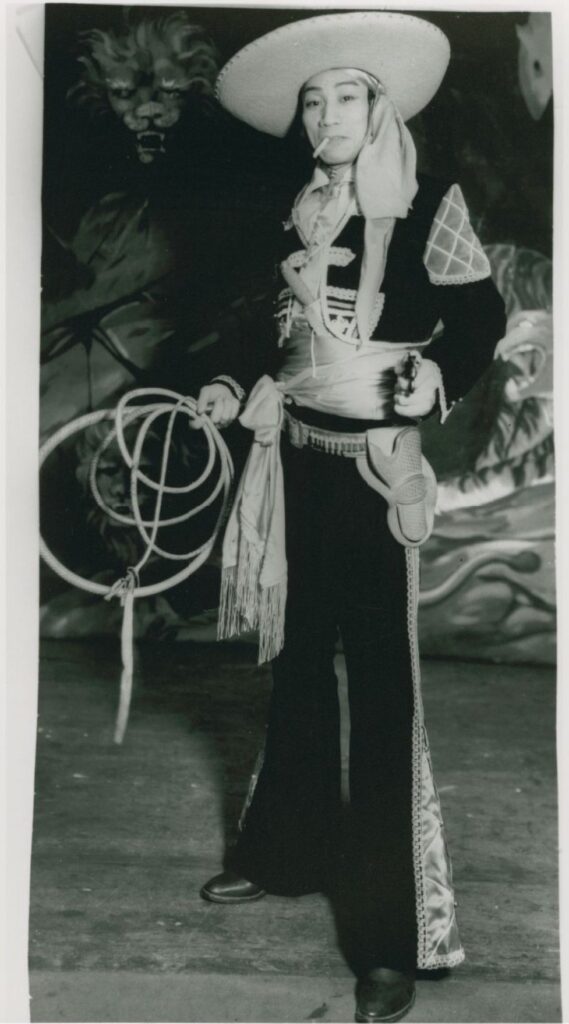

Actor Kwan Tak Hing in Zorro costume, by May’s Photo Studio in San Francisco. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

As a vibrant performance culture in nineteenth-century America, Chinese opera theater was but one early instance in the transpacific history of American music. Other scholars have also shown the robust musical lives of Asians in America. Their scholarship is an obvious resource for teaching American music: Deborah Wong’s Speak it Louder: Asian Americans Making Music and Louder and Faster: Pain, Joy, and the Body Politic in Asian American Taiko; Oliver Wong’s Legions of Boom: Filipino American Mobile Disc Jockey Crews in the San Francisco Bay Area; Su Zheng’s Claiming Diaspora: Music, Transnationalism, and Cultural Politics in Asian/Chinese America; Kevin Fellesz’s Listen But Don’t Ask Question: Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar Across the TransPacific, as well as the Music of Asia America Research Center, among others. However, in the musical landscape of North America, transpacific history remains almost entirely invisible.

In a forthcoming article in Kalfou, I suggest that this invisibility is the result of three forms of erasure. The first is the conceptual space to which Asian immigrants were relegated in American society. They were deemed inferior and therefore inconsequential and of no import to American life and history. Anti-Chinese hostility and violence, such as the Tacoma Method of 1885, drove Chinese immigrants out of towns, and massacres of Chinese were rampant in nineteenth-century America, including massacres in Los Angeles in 1871; Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 1885; and Oregon in 1887. In addition, obstacles to establishing a family—such as the 1875 Page Act—and restrictions on Chinese immigration—such as the Exclusion Act of 1882; Scott Act of 1888; and Geary Act of 1892—worked to minimize the presence and inclusion of Chinese people in the U.S.

“The laws were the official expression of years of anti-Chinese violence,” in the words of the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen. Conceptually, therefore, the sonic presence of Chinese theater was deemed alien and inconsequential, and thus the music of Chinese theater was excluded from mainstream accounts of the American musical landscape.

Chinese musicians. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The second kind of erasure pertains to listening practices, namely how race, class, gender, sexuality, and cultural background structure the way one listens to sound and music. Nineteenth-century American writers, reporters, and travelers created a large amount of writing in which they labeled the music of Chinese theater as noise. The vocal timbre of Chinese opera performers and the instrumental resonance of the accompaniment, by such instruments as gongs and cymbals, were frequently the subject of derision. Mockery of Chinese theater music was so ubiquitous and relentless that it became obligatory in reports by visitors to Chinese theater. The ridicule came to form a lasting impression and became the “truth” about Chinese theater. Chinese immigrants were blamed for creating music too foreign for the American ear. Yet, as the music scholar Nina Eidsheim reminds us, the listener is often “the originator of meaning.” When nineteenth-century writers, one after another, identified the music of Chinatown theaters as inhuman and barbaric, their practice of listening worked to create the “objective truth” about the music—but it also effectively erased the sound of Chinese theater.

The third type of erasure was imposed by legal sanction in turn enforced by police action. From the 1860s to the 1880s, San Francisco and towns in the interior of the state passed numerous criminal ordinances—relating to noise, nuisances, disturbing the peace, and so forth—to curb and silence the sound of Chinese theater. Chinese musicians and opera performers were arrested, jailed, and fined for performing and making music, while theaters were routinely raided for failing to comply with ordinances. Arresting musicians and taking punitive action against them criminalized the musical performance and the space. The criminalization of the theaters’ sonic characteristics figured prominently in popular perceptions of Chinese theaters and Chinatown.

Collectively, these forms of erasure had grave consequences. They made the transpacific history of American music in the nineteenth century illegible to American music history, and few now are aware that this music constituted an important part of the public culture of the American West. Among the stark consequences of these erasures, which are sustained by popular culture and textbooks, is that Asian Americans can also unconsciously internalize their own historical racial invisibility. But we can uncover the traces of this history. It requires a keen awareness of these erasures and the imaginative opening of our ears to hear the sonic presence in history.

Cantonese opera performers in different roles on stage, by May’s Photo Studio in San Francisco. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Clearly, then, to uncover the transpacific history of American music we not only need to reconceptualize and release these Chinatown theaters from their long silence and invisibility. We also need to divorce them from the myths that imprisoned Chinese immigrants through stereotypes and denigration. Here popular music is culpable, as in the enormously successful Tin Pan Alley song “Chinatown, My Chinatown” (1906) by William Jerome and Jean Schwartz. This famous song, as Charles Hiroshi Garrett wrote, “constructed Chinatown through music” and retains its racialized message “to a significant degree today.” With a meandering melody, the lyrics racialized Chinese people through an opium-laden context and pejorative slurs. It became a jazz standard and was omnipresent in negative portrayals of Chinese people in 1920s films. As the jazz guitarist Danny Barker recalled in his A Life in Jazz, it made the audience “all anti-Chinese” and wish for Chinese people to be killed. Indeed, the song’s demeaning and racist message was made grotesquely clear by caricature with hair queues, chopsticks, and gibberish in the film of the same name

Today, the song continues to be performed and recorded as a jazz standard. It has become a sonic marker and cultural symbol of Chinatown and Chineseness in video games, such as Mafia, and movie soundtracks. As the former Director of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, Franklin Odo, astutely noted, this song, bearing a significant legacy and lasting historical significance, portrays derogatory images of Chinese immigrants as weak, pitiable, and illegitimate.

Thus, I want to ask: Could there be a connection between this classic American song racializing Chinese people and America’s rampant anti-Asian violence, in which elderly Chinese people have been beaten, many to death? The enormous rage so many of those perpetrators felt toward the weakest contingent of Asian Americans, the elderly, surely has come from somewhere, and expresses a certain conviction about them as inferior and worthless. This week, while listening to the familiar melody of “Chinatown, My Chinatown” in several renditions, a few images from the news sprang to my mind. One was a young man running across the street to viciously jump-kick the face of an old Chinese man sitting on a walker and waiting for a bus, knocking him to the ground. The despicable, brutal act was caught on a surveillance camera in 2020 and went viral. Such images have become all too familiar. Recalling that one, I realized that “Chinatown, My Chinatown” is not simply a “cultural attitude toward a specific immigrant group” or “racial imagination,” it’s a justification for racial hatred and crime.

American music studies has a role to play in addressing anti-Asian violence. Thoughtfully including the transpacific history of American music in the research projects we conduct and in the courses we teach will do more than make Asian Americans visible and audible. It will help us, our colleagues, and our students to reimagine the racial terrain of America’s musical past. Teaching Asian Americans’ experiences, as Jennifer Lee notes, “will help assuage anti-Asian bias in our departments, our institutions, our disciplines, and will help disrupt the pernicious stereotypes that harm not only Asian Americans but also other people of color.” Expunging anti-Asian stereotypes is crucial to addressing anti-Asian hate and violence and to creating a more just society.

Music is vital in fighting anti-Asian racial crime.

A version of the essay is forthcoming in a special issue of American Music that will celebrate the journal’s fortieth anniversary.