If I Die, I Wanna Die in the Suburbs: Pop-Punk and the Crisis of Neoliberalism

The Wonder Years’s “We Could Die Like This,” the third track on their sardonically titled album The Greatest Generation (2013), describes a man returning to his desolate, suburban Rust Belt, town. As “the memories flood back” he is forced to reconcile his complex feelings toward his upbringing. As he goes through the “worn out” city, he remembers “the anniversaries of the bad things” and the faint smells of True Blue cigarettes and Coppertone sunscreen that still linger. The city is cold, recalling the brutal winters that “turn boys into men.” While the narrator thinks the daily life of the suburbs is mostly “drab with muted colors,” he ultimately realizes that antiquated notions of stability are really what he desires. He accepts that “If I die, I wanna die in the suburbs.” This line is then played against the idea of passing away from “a heart attack shoveling snow/all alone.” The spectacle of dying in a bitterly realist fantasy of the suburbs is, disturbingly, more comforting than the narrator’s actual life. Such themes resonate throughout the band’s catalog; in fact, the header image for this article is the cover to their album Suburbia, I’ve Given You All and I’m Nothing. The Wonder Years’s pessimism toward outdated conceptions of suburban comfort is hardly unique among pop-punk bands. Many pop-punk songs (and especially those written after the genre’s commercial boom in the early 2000s) mourn the loss of the way things “used to be.” In this essay, I argue that the song’s complex relation to suburbia should be contextualized within discourses of neoliberalism. By providing a close reading of the song, I hope to explain how some pop-punk songs channel millennial frustrations with the social tragedies that have emerged because of our recent economic zeitgeist.

Such a scholarly intervention is useful because the vast majority of academic discussions of emo and pop-punk (although different, for simplicity’s sake I will treat the genres as interchangeable) singularly focus on the genres’ complex, and often contradictory, performances of gender. As Matthew Carillo-Vincent puts it, emo and pop-punk allow us to “think about what a criticism of normativity looks like when it comes from the normative subject.” If screaming, for example, is the sign of an oppressed minority, then what does it mean when a straight, white, college-educated man screams? Since showing emotion and screaming are frequently considered feminine, but most pop-punk singers are men, scholars often analyze emo as symbolic of the privileges and contradictions of pluralistic approaches to masculinity in the 21st century. Indeed, one can’t talk about the genre without discussing how progressive tropes of masculine emotionality reproduce age-old tropes of misogyny. This scholarship is insightful and compels readers to critically conceptualize emo and pop-punk beyond what, at first, appear as rather shallow texts.

But to only focus on gender perhaps misses pop-punk’s explicit lyrical discontent over the decline of middle class dreams brought about by neoliberalism (e.g., Spanish Love Song’s “Brave Faces Everyone”). David Harvey defines neoliberalism as “an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.” By the early 2000s, at the same time that pop-punk experienced its own commercial boom, that free market narrative began to be told more frequently as a discouraging story about exchanging social welfare for profit. To me, there are resounding echoes between that changing narrative about economic profit and the solidification of pop-punk’s narratives of disaffection. A millennial born in 1981 who bought Green Day’s Dookie (1994)on their 13th birthday would have seen these massive shifts occur over the course of their life.

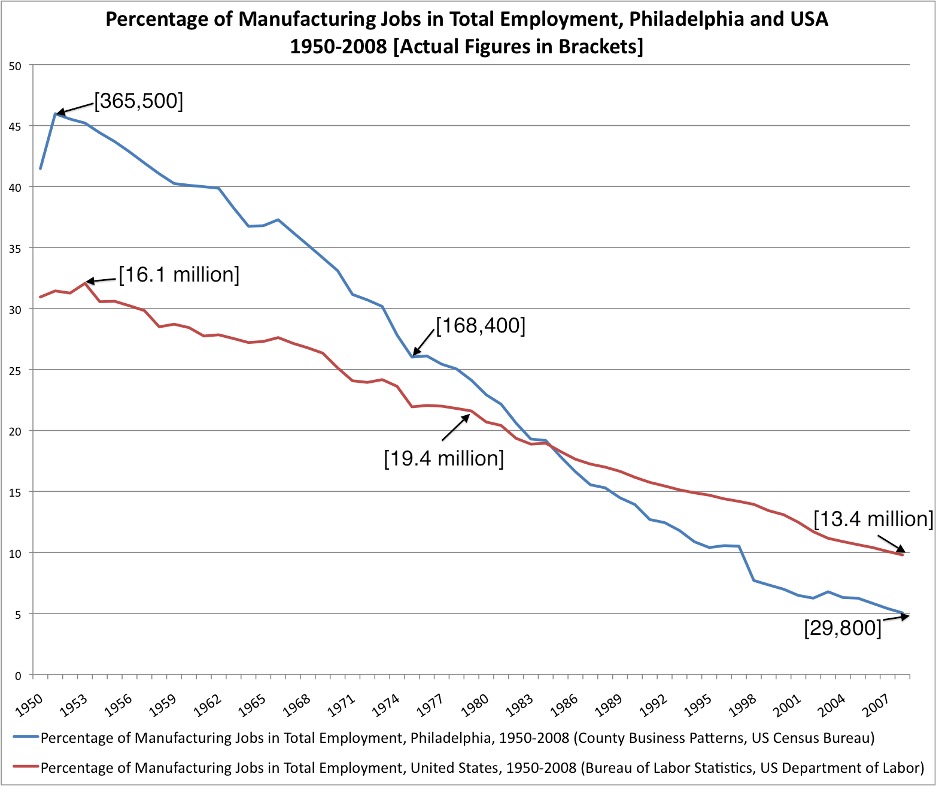

For most, the gilded promises of neoliberalism were a disaster. Industrial towns in the Midwest and Rust Belt (such as the industrial South Philly basements the Wonder Years “came out swinging” from) were decimated by mass layoffs, declines in unionization, and the destruction or privatization of any form of social welfare. Compounding these issues, banks were willing to give out high-risk loans that eventually led to the economic crisis of 2008. After the crash, housing prices skyrocketed while wages remained stagnant. Shortages in the housing market have made it so that millennials are much less likely to own their own home or accumulate wealth when compared to their parents. This created a generation of predominantly white men who were promised a specific suburban fantasy that never came to be because neoliberal policies shrunk the middle class. Changes in pop-punk mirror such economic shifts. After the housing market crashed, pop-punk went through an underground revival led by bands like The Wonder Years, Knuckle Puck, and Modern Baseball. Reviews of these artists’ works note that the sound and lyric content of the genre became “darker and more mature.” If pop-punk is a normative critique of normativity, then we should remember that class is a form of hegemonic normativity. The genre represents the casualties of neoliberalism’s inability to uphold the standards of middle-class life.

A chart that shows the decline in traditional manufacturing jobs in the US and Philadelphia, one of multiple indicators of the decline of the middle class in Philadelphia and the US (from https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/themes/workshop-of-the-world/)

Critics and The Wonder Years seem aware of the political undercurrents of the music that capture “a disaffected alienation” about “growing older but not necessarily moving forward.” Critic Luke Harlow, who similarly relates the album to the “aimlessness and loneliness of 21st-century American life,” says, “The Wonder Years seem to make the case that things have only become worse.” When discussing the 10-year anniversary of the album, lead singer Dan “Soupy” Campbell recounted, “When you’re young and you’re making art like this, you have this feeling somewhere in your gut about what’s wrong, and you want to write music about it, but the specifics of what it is aren’t available to you.” Campbell clarifies how his world view influenced the title of the album (The Greatest Generation). In contrast to the actual “Greatest Generation,” he argues that a truly great generation would be one that could build “an equitable future, a just future, a sustainable future,” as opposed to the collapsing economy that millennials inherited. Such a statement is similar to critic Mark Fisher’s claim that neoliberalism instills the belief that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

When read in this light, it is clear how a song like “We Could Die Like This” taps into a contemporary frustration with the current economic reality. In my reading, the song argues that the suburbs, while imperfect, used to symbolize the potential and hope for a better life. Now, they represent the hollowed-out shell of broken promises. The first lines of the chorus (“Operator take me home / I don’t know where else to go”) emphasize this reality: there isn’t anywhere else to go. The “city is just too worn out” with “no strength to pick our hearts off the ground” to allow people to move forward. All that is left is the fragmented remains of the dreams that once seemed nearly universal in this country. The conditional nature of the title (“We Could Die Like This”) emphasizes this point. We could structure the world to allow for these cities and individuals to flourish, but we, as a society, choose not to. The bittersweet realization of the song is not that the narrator doesn’t want to return to his hometown, but rather that he can’t. I find the contrasts in the song to be highly evocative of this inability to achieve comfort. The narrator reminisces about watching the Philadelphia Eagles play as a child, only to bring up the tragic memory of the team taking the field for the first time after star player Jerome Brown died in a car accident (“We watched the 92 birds / take the field without Jerome Brown”). The story serves as a macabre allegory for the poisoned memories of the past that used to hold so much promise.

But pop-punk is not all doom and gloom. In fact, there is power in pop-punk’s unserious response to a deeply serious situation. In my opinion, what makes pop-punk’s response to neoliberalism so interesting (in contrast to jazz, contemporary classical music, or more mainstream popular music) is the way it counter-scores this hyper-pessimistic outlook with sing-along hooks, anthemic choruses, witty one-liners, and fast tempos in bright major keys. For a genre that’s all about how bad the world is, it is joyful music. For every moment of sullen despair, a new chorus comes, a new sing-along that seems to capture and channel such disillusionment into something that feels like there is something better. If everyone is singing in unison about how bad the world is, maybe something could change.

“We Could Die Like This,” which is quite musically upbeat, captures this affective resistance. The tune reaches its emotional climax during its bridge, where the final line of the chorus is repeated over a cacophony of background vocals. It is big, brash, and charged. Every time I hear the song, I can’t help but sing along, knowing that I am not the only one who feels trapped in the never-ending cycle of dismay and disaster. The imagined community of the gang vocals is quite important. Notably, the song leaves the “we” in “We Could Die Like This” vague. There is no friend, let alone a romantic partner, in the song. Even the idea of dying alone from shoveling snow by yourself seems specifically unique to modern generations. For a number of social and economic reasons, millennials are significantly more likely to live alone and not have a family. The invitation to sing thus encourages the listener to imagine themself within a community of similarly disaffected people. Perhaps paradoxically, the emptiness of the genre’s lyrical content empowers the listener to realize that everyone listening is being equally crushed by the weight of the world. What does it mean if seemingly everyone feels robbed of their sense of progress? Pop-punk captures the affective disenchantment of the conditions of late-stage capitalism. The genre identifies a longing for a more simplistic life where a single income could support a loving family and community. It yearns for a world where parents would be able to support their kids so each generation lives a better life than the previous one. Pop-punk creates a loving and caring community out of the disappearance of these evaporating dreams. It is worth noting that The Wonder Years are signed to Hopeless Records. The record label, which has numerous major pop-punk acts on its roster, ends its mission statement with the fitting line, “Yup, we’re Hopeless, but we’re not gonna let that stop us.” Where neoliberalism attempts to strip us of hope, pop-punk fights to maintain the fleeting prayer of dying in the suburbs.