More Troubling Failure(s): Situating Bodies and Research in Art

Ed. note: This essay is an offshoot from a lecture originally presented as the AMS Committee on Women and Gender Annual Endowed Lecture. Fred Maus and Tes Slominski read responses to that spoken delivery. These are also available to read (Maus; Slominski). I am grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with Andrea Bohlman. Together we nudged the original lecture to its present exploratory, experiential edge.

Starting Trouble

Warning: This presentation juxtaposes fragmented gestures, stories, media, and commercial interruptions. It is experimental and engages Jack Halberstam’s “the queer art of failure” and “scavenger methodology” to disrupt traditional ways of knowing. The essay departs from linear sensibility of time. I invite readers to rummage through the essay as a scavenger would: pick and choose which sections you would like to read (or engage with as images or sounds) and in any order you desire. As a scavenger, I appreciate fluctuations arising from juxtapositions—real or imagined. Let’s stir up failure and welcome how it stimulates new knowledge.

In Female Masculinity, Halberstam writes:

A queer methodology is a scavenger methodology that uses different methods to collect and produce information on subjects who have been deliberately or accidentally excluded from traditional studies of human behavior. Queer methodology attempts to combine methods that are often cast as being at odds with each other, and it refuses the academic compulsion toward disciplinary coherence.

It is my intention to offer unconventional, alternative practices as one path to inclusivity, to urge new voices be heard at the table, so that our academic, musical, and creative communities might benefit and grow.

I am curious:

What if our survival depended on failure?

Invitation to Scavenge

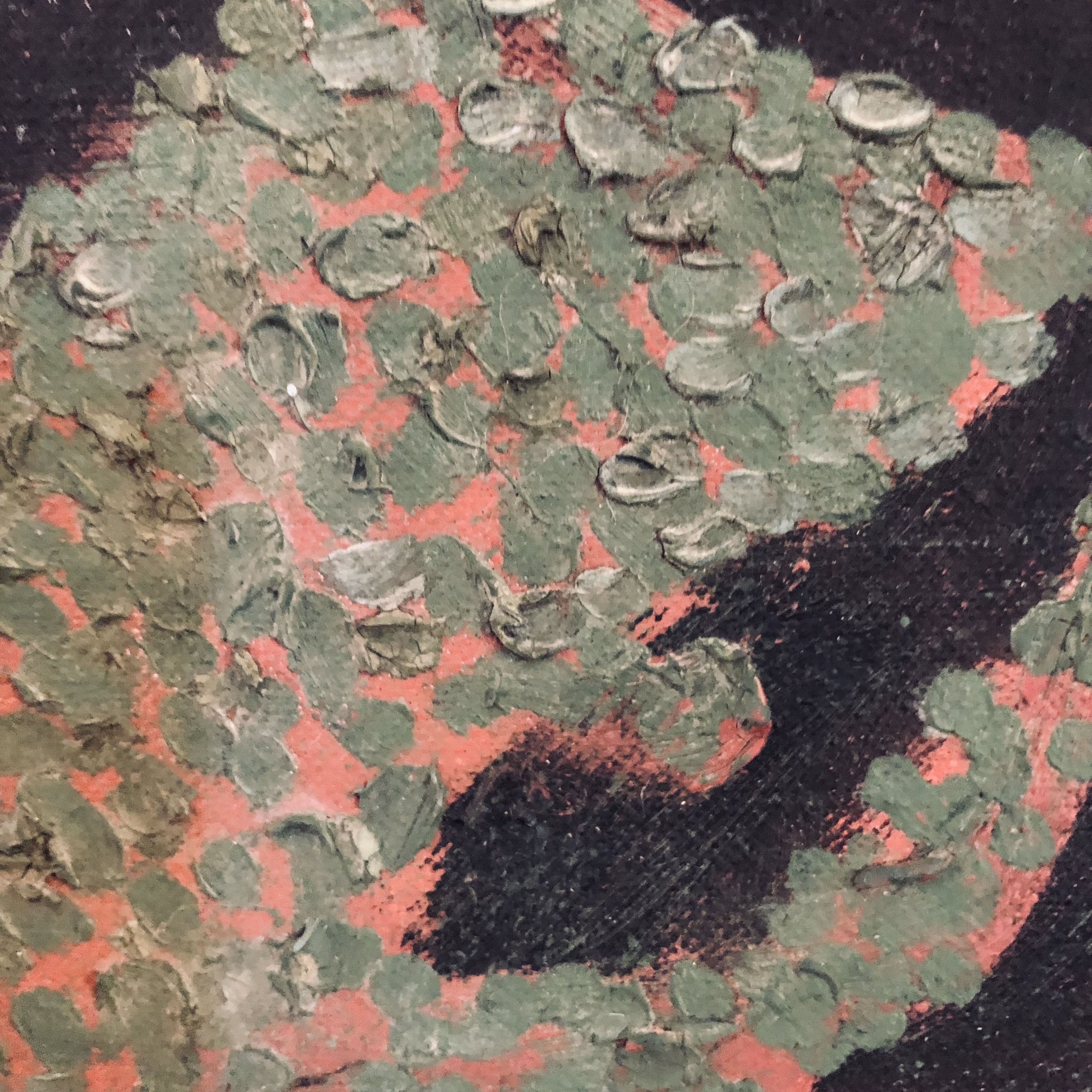

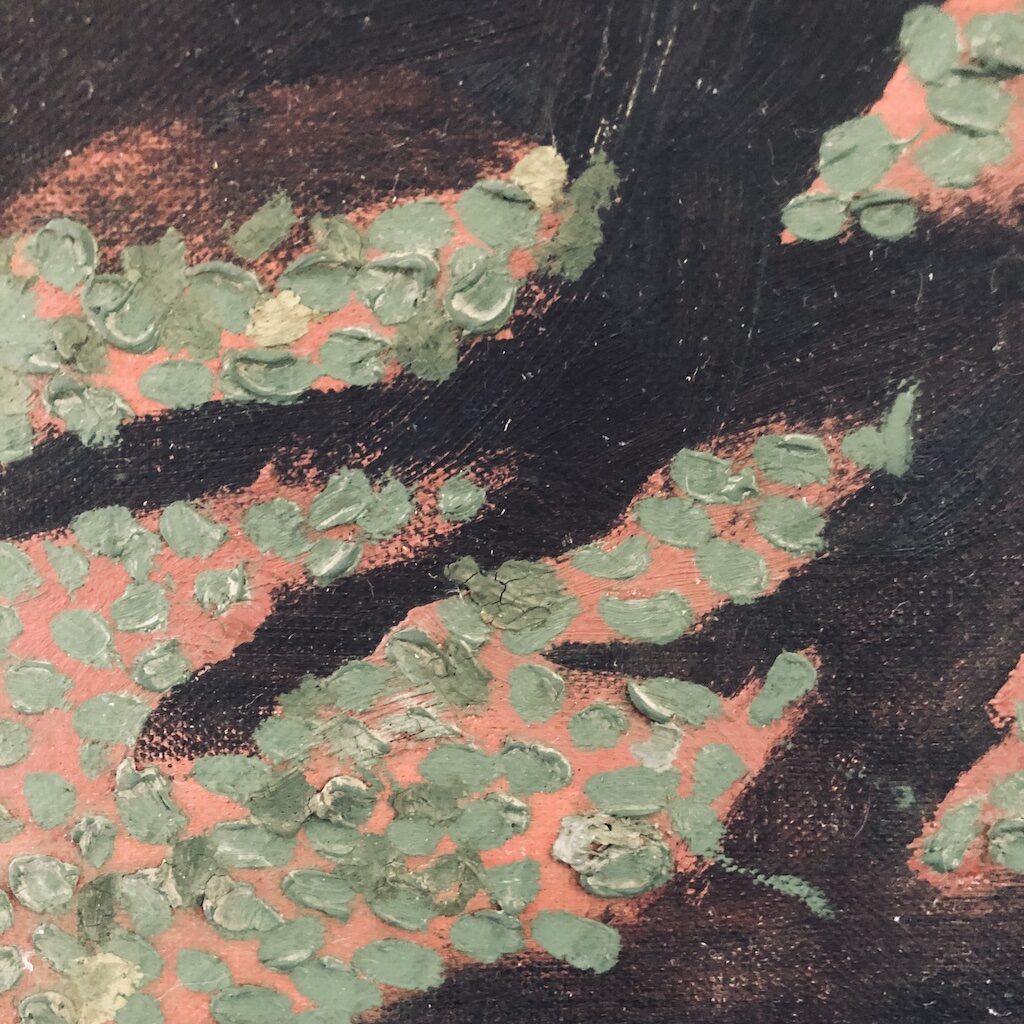

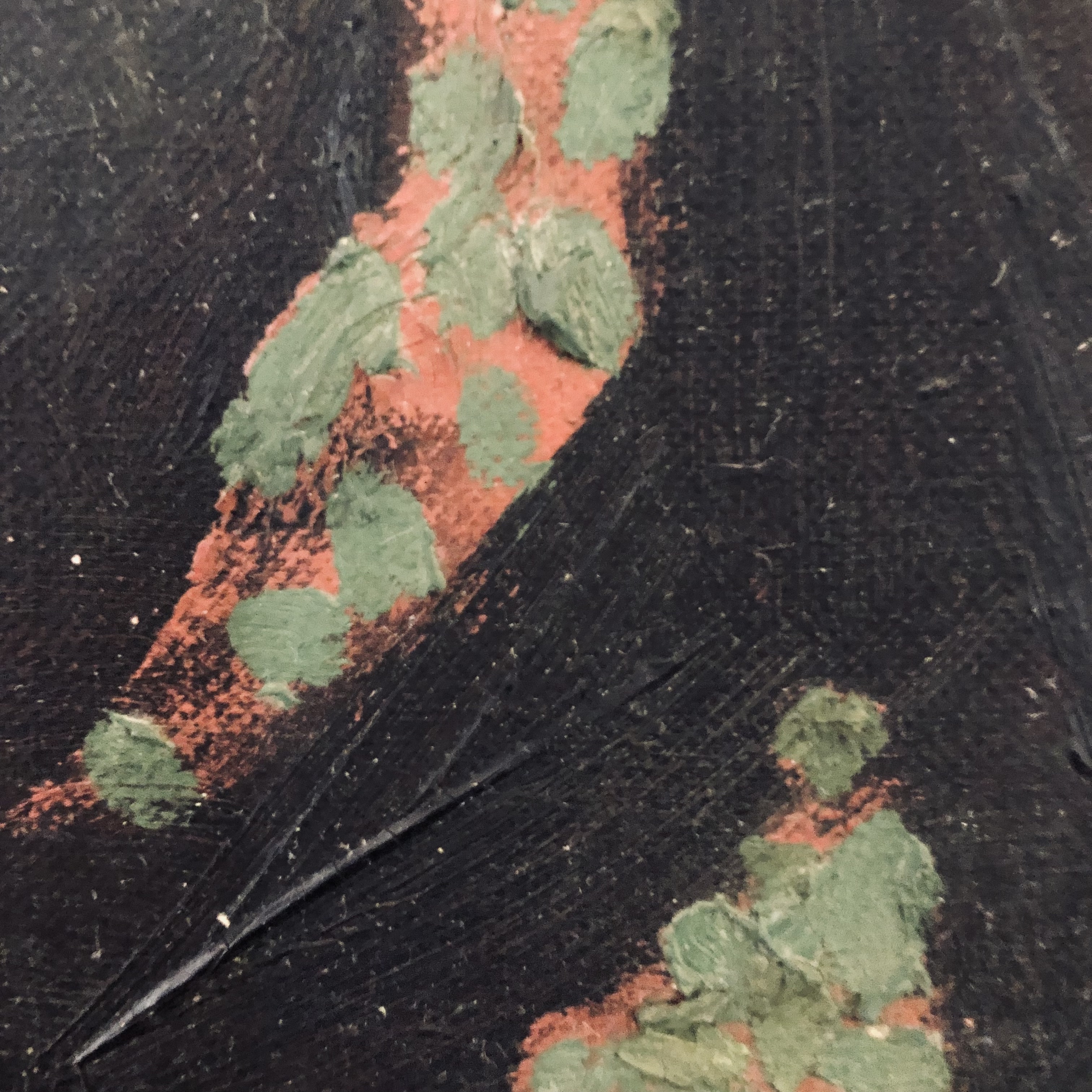

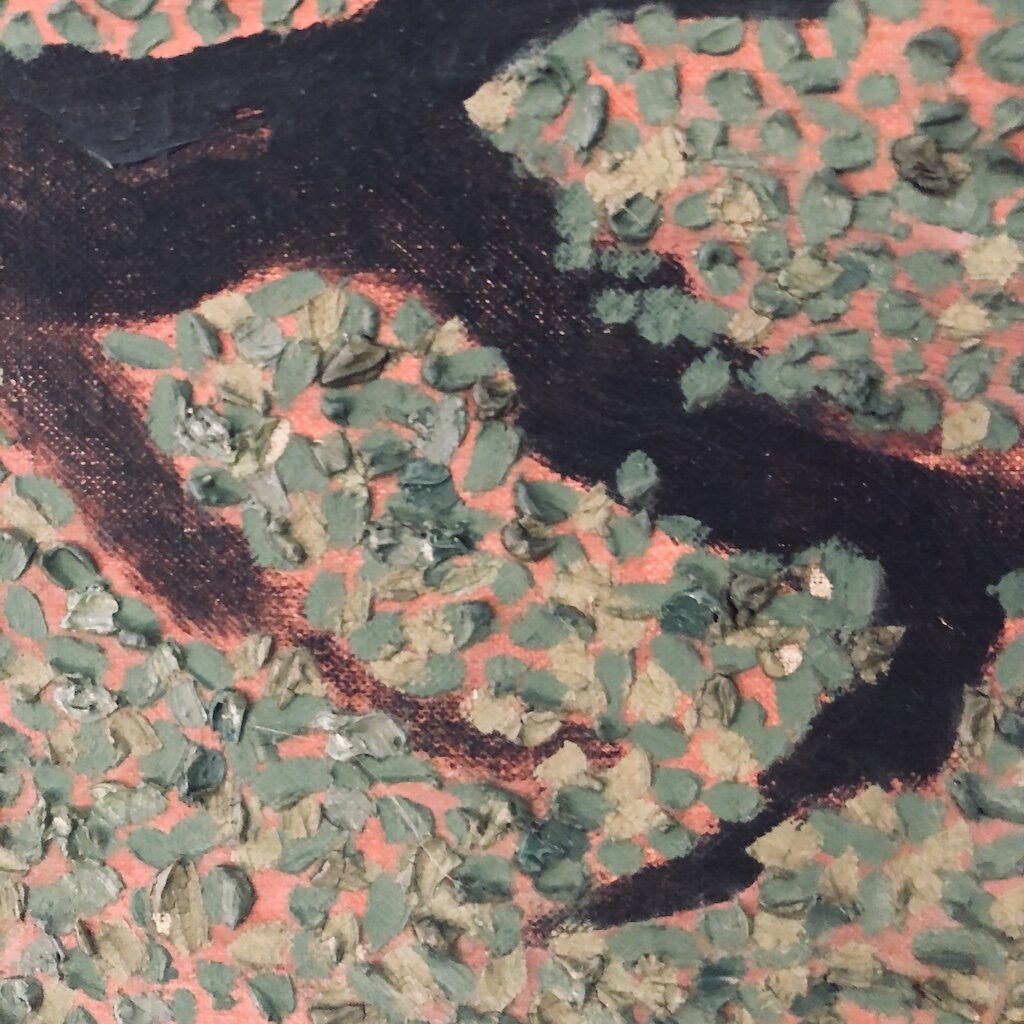

Click on an image or header below to rummage through the fragments and sounds here. At the end of each section, you’ll be invited to return to this collection of images pieced out of the painting at the top of this essay and explore anew.

On Naming

Consider the sound world offered here, recorded by Curtis Bahn.

With those sounds in ear, I invite you to read an excerpt from my book that draws from this very soundscape, Arousing Sense. The passage draws from my fieldnotes about a voyage to Machias Seal Island Wildlife Refuge, approximately twenty miles off the coast of Maine, to stand inside of a 3′ × 7′ wooden box for the privilege of observing puffins in their natural habitat. Strictly, only a certain number of people are allowed to venture onto the island. The day began in Cutler Harbor around 6 a.m. Several boat trips and hours later we landed on the island and the naturalists guided us to our blinds.

The wooden blind intrigued me. Painted dull grey, the exterior attempts to camouflage the rectangular box and its human inhabitants among the grey boulders. Although merely constructed from basic pressboard and 2′′ × 4′′ lumber, the bare, natural wood interior felt warm and rustic.

Once in place, a variety of sea birds surrounded the little blind. Literally. Atlantic puffins, as well as razorbill auks, landed on the blind roof to congregate, webbed feet creating sharp percussive slapping sounds alternating with a muffled shuffling noise, perhaps from waddling feet. Groups of puffins congregated on top of large boulders just outside the blind, while others peeked out from crevices between boulders as if they had their own sheltering blinds. Often nesting takes place below boulders, and I noticed high traffic and well-guarded areas near such mini caves. The sunny day, enhanced by the brilliant reflection of sunlight from the ocean, green plants, white rocks speckled with yellow-orange lichen, and white excrement, presented a vivid backdrop for viewing sea birds. Despite their small stature, puffin characters loom large. They display white feathers on their torso and black wing feathers. Their comically large bill with bright orange stripes, large eyes, and orange feet contribute to the distinct puffin character. Gazing out from the gloomy blind, I kept marveling at the almost unnaturally flashy, orange-colored beaks, eyes, and legs. The smell scape ranged from a subtle, fresh, and salty aroma to the pungent, acrid smell of thousands of birds.

The soundscape encompassed a diverse auditory terrain—a continuous lapping of waves, splashes of diving puffins and other water-related sounds, beaks clicking together, wings flapping, a wide array of sea bird squawking, and general cacophony. Loud? Oh yes. Deafening squawks erupted from the flock when an incoming bird flew in from the ocean with a beak loaded with fish. Curiously, the persistent sound of the ocean, so ever-present and noisy while traveling by boat, became filtered once on the island. I imagine that the muting was partially my own sensory filtering, not only due to my excited anticipation to listen to the chaotic bird chatter and wing flapping, but also because I was now habituated to the wall of ocean sounds.

I struggle not to anthropomorphize and overlay my interpretations of what I imagined these small birds might be doing, thinking, and even feeling. But I confess, my attempts to avoid interpreting and characterizing their behavior has not been easy—waddling movements appear comical; flying back from the sea, beaks loaded with sand eels for their chicks, seems to indicate a nurturing side; puffins snuggling together appear lovingly affectionate, and their romping between boulders entertaining. As we cannot assume what another human’s experiences or thoughts are at any given time, we surely need to resist such interpretations across species, especially without long-term specialized ornithological field research. My mind understands the logic, but resisting interpretation requires effort. The undertaking poses multiple considerations regarding embodied “knowing,” as it acknowledges assumptions based on past experiences and sensory filtering.

Unfortunately, someone on the boat loudly declared that puffins and razorbills sound like chainsaws revving up. The “sounds like” comparison conjured countless personal sonic memories of chainsaws for me. Then, when I heard the actual sea bird cacophony, I found it difficult to shake the sonic translation foisted upon me prior to my lived encounter. ’Twas a sensory spoiler that would impose upon my first sonic acquaintance with puffins—a mere suggestion of an auditory memory, or schema, that would initially not allow me to experience the actual puffin and razorbill chatter. This sensory spoiler illustrated a perfect failure, bridging experience, transmission, memory and interpretation.

This sensory spoiler illustrated a perfect failure, bridging experience, transmission, memory and interpretation.

Luckily, once in the blind, I found the sound world deeply moving and transformative—so unlike one thousand chainsaw artists or horror flick maniacs surrounding our blind. More importantly, the auditory experience constituted only a fraction of the lush sensory immersion, alongside the movement, smell, feel, temperature, light, emotion, and so on. The parsing of the senses, while a convenient means for organizing observation, compartmentalizes such a truly elaborate and lush world of sensory experience.

I often wish that language did not impose on an initial experience. The human capacity to use language, paired with our tendency to compare new experiences with the past, helps us to communicate and grow. Schemas—frameworks that represent experiences, categories, and patterns that we have previously encountered—help us to discern, learn, and broaden our sensory vocabulary and provide a theory of learning through information processing and comparative judgments. Growth arises through a perturbation of previously experienced schemas. Sure, I understand the concept, yet it provides me with little solace while entertaining chainsaws and puffins.

Transmission Failure and Time

I am a transmission specialist. I am fascinated by embodied transmission—how culture is learned through the body. During fieldwork in Tokyo I realized that the senses are vehicles for transmission of embodied knowledge. My attention since then has been focused on sensory transmission. As a performer and artist, I am particularly drawn to how culture is transmitted through ephemeral practices. The key here is the relationship of time and the understanding of sensory awareness—that information in any sensory modality flows and unfurls in time.

How does “troubling failure” fit in? Bodies are exquisitely imperfect, sensory awareness is imperfect, and transmission is imperfect…and it is this very mashup of embodied imperfections—alongside intention and “productive failure”—that deeply intrigues me.

I invite us to consider failure from different perspectives. Narrowing the terrain, I draw our attention to failures of transmission. While I’ve written about transmission failure regarding what researchers selectively exclude from their writing, in this essay I act out failure by focusing on transmission failures pertaining to stale categorizations, sensory and experiential translations, and memory.

What if our survival depended on failure? On scavenging?

As musicians and performers in time-based arts, we specialize in the performance and examination of the flow of time. Can we employ our concentrated attentiveness to sound and apply it to other sensory modalities? All sensory information unfolds over time. Sensing change is observing time. I encourage us to attend to and embody sensory modalities beyond sound. Because this essay wrestles with the outlaws of time and sensory awareness within transmission failure, I propose we also mess with disciplinary categories organized by modalities of sense, to challenge systemic categorizations.

A Scavenged Story

This scavenged story may be difficult to read. I invite you to contemplate a challenging practice that allows vulnerable moments to emerge, affording new perspectives.

My father, now passed, had dementia. At a certain point he realized his lack of recall. I remember sitting with him, sipping our tea, when he looked up and said, “I am sorry I cannot remember…” As his voice trailed off, I leaned forward, cupped his jawline in my hands, and asked, “Are you enjoying my company now?” He brightened up “OH YES, YES!” Me, “I am enjoying this time with you too. And later today, when you have forgotten this conversation, we will enjoy that time as well… fresh! you raised me doing okeikogoto (practice arts) and Buddhist practices…Now is where we are.”

Our performance repeated itself. Often. Looking back, I can appreciate the rhythms of our recurring phrase. I can greet the repetition with an embodied sensibility, meaning that the body tends to appreciate repetition to strengthen transmission, memory, and to arrive at an experience of heightened spontaneity arising from one’s deeply focused attention during an activity, what the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi theorized as “optimal flow.” Repetition of the scene with my father offered nuances to contemplate and it reinforced compassion for times past, for a challenging childhood.

In research and artmaking, I keep returning to voids—empty transmission. While I have been focusing on what I call “transmission failure” for some time, this repeating encounter with my father shook new insights into transmission failure and memory. I scavenged through my childhood memories to connect with my father’s mind in dementia. The story clarified a telescoping of time, something cognitive scientist, and my collaborator, J. Scott Jordan refers to as multiple times-scales, where repetition of an activity over various spans of time can reveal patterns, heightening an awareness of time and consciousness.

In my collaborations with Scott that examined multiscale entrainment, we noted how transmission practices reveal multiple timescales reflected in embodied cognition. Using the Japanese dance studio as a case study, we analyzed the extent to which the

…studio can be conceptualized as an external scaffold that affords (a) a space for student–teacher interactions, (b) the long-term maintenance of a historical–cultural tradition, and (c) the pedagogically driven emergence of a rich phenomenal sense of belonging to something larger than the timescale of one’s immediate movement planning.

p. 272

Such multiscale, cultural modes of transmission greatly influence how we attend to sensory information. These filters problematize notions of sensory “translation,” or how we make sense of our situated experience (see Classen, 1993, 2005; Howes, 1991, 2005). How we learn to move involves a multiscale overlap of several sensory modes of transmission. Noticing which sensory modes are emphasized, even prioritized, in different movement practices unravels a diversity of personal, social, and cultural influences.”

p. 275

For me, the recurring scene with my father became my telescope into a sense of deep time where the repetition on multiple time scales imparted new insights on failure.

Teachings of the Absurd in Failure

I wonder if you have experienced absurd failures similar to the following story. I stopped on the side of a country road to ask for directions. The response, “Take the first right, then bear left where the old oak tree used to be.” I turned right and expected to see a large tree stump on the left. No. Key nonsensical fail here “used to be.” This would be productive failure. I got lost without the tree-stump marker, and the extra eight minutes afforded a different adventure, and certainly a different perspective.

Lack of material, in this case a tree, beckons us to consider how erasure or absence functions, how it might provide edges of nothing, or a broadening and sharpening of sensory awareness, or a scrutinizing of memory and transmission. Was a musical practice from years past so commonplace that the particulars of musical practice were not deemed necessary to notate or articulate? Of course. However, lack of material or lack of memory can also enable a masking that delineates inside or outside. Hegemonic protections. Clarity of social circles. Philosophical or spiritual powers or beliefs. Culture-jamming, in the case of convenient misplacement or forgetting? The context surrounding each case of omission, intentional or not, can offer a variety of insights that are particular to the absence. A closer examination of the edges of nothing might suggest an inspiring overlooked path to knowledge production and transmission.

Our survival depends on failure.

A Sensory Prompt

What do you sense when you smile so deeply and strongly that your eyes close?

Try it. Hear and feel anything? As you release, notice what stirs in your awareness.

Draw or jot down a few words to savor later.

Query: Did you notice if you went directly to theorize about the experience before you allowed yourself to sense?

Illegibility as Failure

Sensory transmission failures are embodied failures: 1) embodied in physical bodies and 2) embodied in systems that teach and control bodies. Contemplating transmission failures of the physical body can present fresh critical and creative perspectives, yet also painful territory. Illegibility in embodied transmission, for example, can produce ruptures and chaos.

Imagine the challenge of writing from a “fragmented subjectivity”—in my case, embodying a mixed-race presence in the field. I have support from my ethnomusicologist colleague Christi-Anne Castro, writing in the edited collection Queering the Field. She asks, “Can failing at normative ethnographic writing also succeed in conveying queer subjectivity? To me, queerness is a fragmented subjectivity in which various levels of outness play a role in the episodes of my personal, musical, and professional life… For instance, my queer voice in ethnography might be found in an optimistic failure to convey straightforward meaning, instead favoring a felicitous flow of phrases, at the end of which one experiences a sensation of knowing.”

Christi-Anne’s voicing of “failing at normative ethnographic writing” and “fragmented subjectivity” helps me to trouble my own context and perspective. Let me explain. For mixed-race individuals, our very presence displays the sexual “act” of race mixing, of miscegenation. As I wrote in Sensational Knowledge, in reflection on my life as a performer and ethnographer, the taboos of racial boundary crossing are embodied and on display, so that our daily lives, our very presence, can become confrontational, performative enactments that puzzle people, who constantly remark: WHAT are you?

Let’s take a closer look at that question. Note how the inquirer, by consciously or unconsciously attempting to minimize the uncomfortable subject of race, neglects to include “race.” However, the very absence of the word “race” executes further damage, as the resulting question objectifies the mixed-race individual. Ironic. Literally, a double failure transpires because of the erasure of one word. Illegibility confounds people who desire clear designations.

This postmodern embodiment-failure freely queers new spaces—simultaneously rejecting normative binaries while also embodying the conflict. Race crossing is on display, as I fail to look, sound, move, or feel like either of my parents. Here, I offer myself as illegible, as a child of miscegenation, peering in from a corner of the room. Although the room remains dark, periodically a faint light brings into focus my complicated family. The illegibility of the shadowy room offers me space for a reflexive stance to rally a between-ness so chaotic, but necessary, at this time in history. Perhaps this is why I often reach towards failure, extending myself to the thorny vulnerable edges of productive failure, to notice the sharpness so that it can orient me in the dim room.

My survival depends on productive failure, as a repeated performance.

Disciplinary Failure

The silo-ing of academic disciplines is a systemic, embodied failure rooted in sensory partitioning. Disciplines on university campuses are organized by sense (eye-people, ear-people, moving-people, and so on). I strongly believe that neglecting to experiment across disciplines as researchers and artists, only reproduces a continuity of sensory bias.

As students, teachers and, practitioners, have an opportunity to incorporate transmission failure to resist falling into habits and tendencies. Normative habits often occur on multiple timescales—from moment-to-moment habits of sensory attendance and filtering, to tendencies of citing the same lauded texts, to persistent embodied tendencies that endure for decades. When I sense transmission failure, the exposure of ambiguity, illegibility, and aberrance percolates creativity. Productive transmission failure can offer orientation through disorientation.

Everyone needs to try falling down now and then to discover our own vulnerabilities, boundaries, and resilience while playing with gravity. Falling down affirms our frailty, our humanity, and displays that we are pushing our own boundaries of experimentation.

Can we purposely fail while teaching? While workshopping new material?

Can we periodically create assignments or cultivate practices for ourselves that require productive failure?

Moving Failure

Around the time of Hurricane Sandy I found a plastic bag of rolled up rice paper from my childhood. They were practice calligraphy papers from my Saturday morning lessons with Kan Shunshin, a Buddhist monk and kendo master I adored.

The black brush strokes, traces of movements enacted decades ago, revealed our focused attention, yet also fleeting moments where brush steered ink. I recalled Kan sensei standing behind me as I practiced. Periodically he’d clutch my hand in his and guide my arm to form shapes in space that would ink shapes on paper. Sometimes, he painted red-orange-colored lines on top of my finished writing as corrective guideposts. The differences between our lines on this shared space, visible. Because I found these papers just after Sandy swept through our coast, walking to the woodstove to burn them was my first response.

No patience. Lives were lost. Water rushed.

But one pause to unroll these sheets before tossing them to flames, revealed paper nearly my height.

Ground ink inscribed memories of sound and movement long past. The flow of watered-down soot meandered the confusion on the streets and in my mind. Memory, like ink, meanders.

The ephemeral quality of sound reengages us with our own frailty.

The flow of ink and gesture, a form of theorizing embodied sound writing, conflating childhood memories with present gestures.

So, breathing and moving—video camera in hand—brought the life back to rice paper from its brittle state, and saved it from the flames. Torrents of sound and ink.

Surprisingly the presence of the body became starkly apparent with this experiment. The imperfect body, as witness, hovering, breathing, and moving, clearly displays how the point of view of the artist-ethnographer is controlled through framing. Enactive knowledge, as sensational knowledge, became an expression of visual poetry, of poeisis, of making. The video fragments were memory aids.

But most importantly, the fragments were queerly generative in their refusing coherence. In hindsight, I was utilizing Halberstam’s scavenger methodology, experimenting with a variety of methods to collect, produce, display, and transmit information.

Sense and Survival

Let’s remember poet and essayist Adrienne Rich’s classic quote from 1972:

Re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction—is for women more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.

p. 18

I’d like to honor her passage with an editorial twist…

Re-sense—the act of revisiting presence, of sensing with a fresh body, of entering an old text from a new critical direction—is for women more than a chapter in cultural history: it is a queer act of survival.

Let the aberrance and scavenging support our survival.