Unsettling Peter Pan

I have this theory about Indians. Actually, the theory is not really about Indians, it’s about everyone else. Here’s the thing: although I don’t mean to hurt anyone’s feelings, generally speaking white people who are interested in Indians are not very bright. Generally speaking white people who take an active interest in Indians, who travel to visit Indians and study Indians are even more not very bright. I further theorize that, generally speaking, smart white people realize early on that the whole Indian thing is an exhausting, dangerous, and complicated snake pit of lies. And without it ever quite being a conscious thought, these intelligent white people come to acknowledge that everything they are likely to learn about Indians in school, from books and movies and television is probably going to be crap.

Paul Chaat Smith, Everything You Know About Indians is Wrong (2009)

As a person of settler descent who takes an active interest in Indians, who travels to visit Indians, and who studies Indian music, I felt both amused and gutted when I read Smith’s wry words. The term “Indian” (or American Indian) may trigger some readers, but it is a collective name used by many Indigenous peoples in the US. Other terms include Native American, First Nations, First Peoples, Indigenous, and Alaska Native. Smith, a Comanche artist and museum curator, impelled me to reevaluate what I thought I knew about Native Americans and how I learned it, dredging up tacit memories from early childhood.

Like many other white, middle-class children born in the US during the 1950s, Native peoples entered my consciousness in 1958 through the animated Disney film, Peter Pan. The animated film (1953) and Broadway musical (1954), based on early twentieth-century works by J. M. Barrie, embody persistent verbal, visual, and musical stereotypes about Native peoples. Disney’s “Indians” look like team mascots, speak in broken English, and behave foolishly. The “Indian” music is equally wrong, with its crude imitations of Native speech and its musical tropes of primitivism, including the “Indian beat”: Dum–dum-dum-dum. Broadway’s Indians fare no better. I never saw the show during childhood, but the 1960 NBC live broadcast of the musical, and its numerous adaptations, still circulates via YouTube. The NBC broadcast patronizes the “braves” through costuming, make-up, wigs, and choreography. Tiger Lily’s “Ugg-A-Wugg” song, set to the Indian beat, infantilizes her. In other words, everything Peter Pan tells us about Indians is “crap,” yet the film and musical remain a treasured part of childhood in the twenty-first century, and they have conditioned generations of non-Natives to disdain Indigenous peoples.

When Disney released Peter Pan in 1953, the US Congress established policies to terminate Indian tribes and relocate Native peoples from reservations to major cities in its project of assimilation and cultural genocide. There is no apparent connection between the Disney film and federal Indian policy, yet the film manifests the socio-political climate in North America at the time. The loss of language and songs due to federal assimilation policies and practices constitutes a major concern for Native Americans in the twenty-first century, and many Indigenous communities devote significant human and financial resources to redressing this issue. North American academic institutions advocate for unsettling colonialism, which would involve the disruption of settler-colonialist frameworks through analysis, critique, and activism. But is it even possible to unsettle icons of popular culture such as Peter Pan? Here I center the work of three Native creators—Frank Waln (Sicangu Lakota), Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (Chickasaw), and Natanya Pulley (Diné)—each of whom has answered this question through narrative or song, shifting settler perspectives on Peter Pan and providing catharsis for Indigenous audiences.

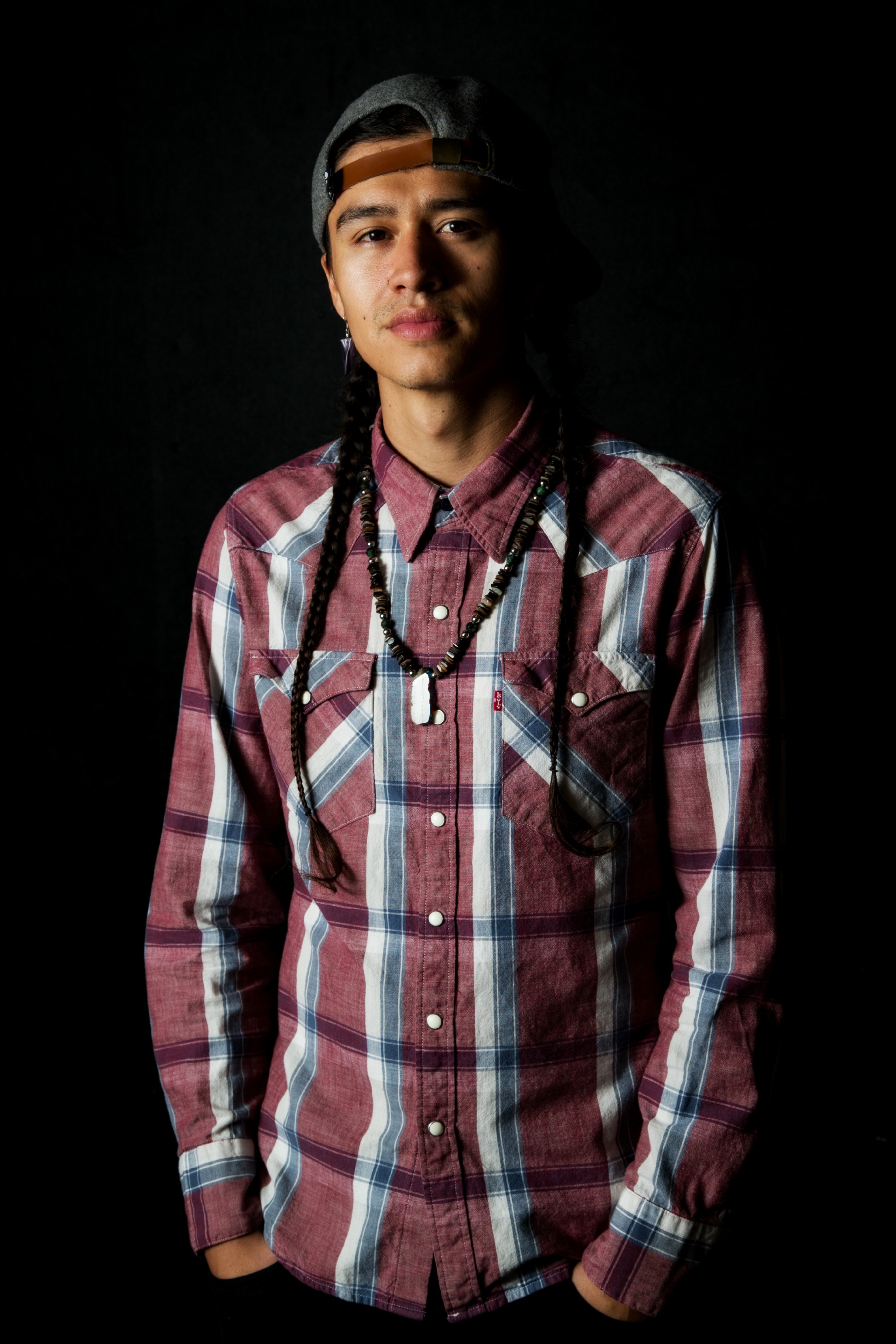

Artist Frank Waln (Sicangu Lakota), whose rap performance subverts a song from the 1953 animated Disney film Peter Pan. Credit Kernit Grimshaw Photography.

Frank Waln is a musician, songwriter, performer, and producer. Like other Native American/First Nations artists, Waln connects with hip-hop through the experiences of racism and oppression Indigenous peoples share with African Americans. In a 2019 interview for the American Writers Museum, Waln explained, “Powerful storytelling can create pathways of empathy and understanding across cultural, racial and socioeconomic divides that were built up to keep us separated from one another. Most Indigenous nations have strong histories and traditions of storytelling so I see my art as a continuation of that tradition.”

His 2015 rap fearlessly subverts the Disney song, “What Made the Red Man Red”. In his charismatic performance at Café Cultura in Denver, Colorado, Waln strikes his chest with his fist to punctuate the “Indian beat” in the remix. The lighting gels shift from red to blue to green to white, symbolic colors in Lakota spirituality, marking the venue as Native space. Through his apparel and personal adornment, he presents himself as a Native person who moves fluidly among Indigenous communities, from ancestral homelands to reservations, and rural to urban areas. He wears a long-sleeved t-shirt with a Native logo, Native necklace, jeans, disc earrings, baseball cap, and long hair worn in a braid. Waln dances as he raps and engages the audience by inviting them to clap along with him. He adlibs at decisive points in the performance. At the start of the second verse, we hear the words “pale face” and “savages” in the remix; Waln echoes these words just before he raps “savage is as savage does,” clarifying who the savages are. After the line “all we get is a god damn mascot,” Waln adlibs “I’m not your Redskin,” mocking the Washington Football Team that has since discarded its racist name. Take a moment to read his lyrics, available here. Waln’s skillful use of words, rhyme, and rhythm refutes the broken English of Disney’s Indians. Disney now places a parental warning on Peter Pan due to its racist content, and in 2021, they blocked it on their streaming service for children under the age of seven, yet it remains widely accessible.

Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (Chickasaw), musical consultant to the 2014 live broadcast of Peter Pan. Photograph by Shevaun Williams.

When NBC reprised a live broadcast in 2014 of Broadway’s Peter Pan, Jerod Tate served as a musical consultant to “salvage” (Tate’s word) Tiger Lily’s “Ugg-A-Wugg” song. Tate, who self-identifies as a classical music composer, founded the Chickasaw Music Festival and co-founded the Chickasaw Summer Arts Academy, advocating for performance and composition by Native classical musicians. Tate stated in a December 3, 2014 interview with Indian Country Today that he collaborated with the show’s musical director, David Chase, to address three aspects of Tiger Lily’s song. First, they changed the opening rhythm, emphasizing the second beat to sound more like a Haudenosaunee Smoke Dance, because Barrie drew inspiration from ethnographies of Native peoples of the Northeastern US. Second, they adapted what Tate called the “Indian breakdown,” where the melody channels Florida State University’s “War Chant,” evoking the repellent tomahawk chop gesture fans make at football games. They substituted a more generic dance tune, which for Tate was “the best anyone could have done.” Finally, they altered the song’s title from “Ugg-A-Wugg” to “True Blood Brothers.” Tate explained, “since ‘Ugg-A-Wugg’ was the word that Tiger Lily and Peter agree on as their call for help, we decided to look at the Wyandot language for an actual word that still fit that rhythm and the music. . . . I went through the Wyandotte Nation in Oklahoma and . . . we came up with the word Owa,he, the Wyandot word for ‘come here’.” (Wyandot is the Iroquoian language spoken by Wendat [Huron] peoples; the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe.)

Motivated by respect for the musical’s original composers and lyricists, Tate and Chase chose to preserve the integrity of the book and music while excising its most offensive aspects. Tate remarked, “It’s important to remember that musical theater, as a genre, is based in stereotypes. There are a lot of musicals that have kind of funky numbers like that. I’m not looking to cover anything up; I was just trying to bring more integrity and authenticity to that particular song.” Rather than dropping the song from the show altogether, Chase and Tate model a collaborative approach to revising a musical theater standard. The 2014 NBC live broadcast of Peter Pan appears on YouTube and the soundtrack is available through Broadway Records.

A screenshot of Carsen Gray (Haida) as Tiger Lily in P.J. Hogan’s 2003 film Peter Pan.

Part of Tiger Lily’s predicament in Peter Pan is the flatness of her character. Barrie describes Tiger Lily as “the most beautiful of the Dusky Dianas . . . coquettish, cold and amorous by turns; there is not a brave who would not have the wayward thing to wife, but she staves off the altar with a hatchet.” Fierce, beautiful, and provocative, Barrie fetishizes Tiger Lily from the start. She hardly speaks in Barrie’s original play and novel, and when she does, she uses broken English. Her visual representations onstage and in film perpetuate images that denigrate Native women. The film version of Peter Pan directed by P. J. Hogan (2003), a renowned Australian writer and director, rehabilitates the offensive imagery. Tiger Lily, played by Carsen Gray (Haida), wears a modest buckskin dress and speaks her line of dialog in a Native language; she has a blue handprint painted across her face. In 2019, a red or black handprint painted across one’s face became a prominent symbol of the murder, disappearance, and sex trafficking that afflicts Indigenous women, girls, and Two Spirit people (MMIWG2S). There is no apparent connection between Hogan’s Peter Pan and the MMIWG2S awareness movement, but for me the blue handprint clearly denotes Tiger Lily’s silenced voice.

Natanya Anne Pulley (Diné), author of Tiger Lily and the Impossible Neverland (in progress). Photograph by Gray Warrior.

Natanya Ann Pulley creates a voice for Tiger Lily in “from Tiger Lily and the Impossible Neverland” (an excerpt from her novel-in-progress published behind a paywall in The Massachusetts Review, 2020). In this work of creative fiction, Pulley imagines Tiger Lily’s autobiography, revealing the character’s thoughts on naming, identity, place, geographic location, relationships, language, and song. Pulley’s Tiger Lily states, “I began misnamed. Before the page turned maybe. Lilium lancifolium. Lilium tigrinum, a synonym. Born of Asian lands: China, Japan, Korea—and also the Russian Far East. I am named such because perhaps I did not care for boundaries at the time. . . . Or perhaps this is what I am told to be.” Pulley bespeaks the conjoined forces of colonialism and exoticism that defined late-Victorian thought, unearthing complexities of which Barrie was probably unaware.

Tiger Lily continues, “There is within this Neverland, but under those wigwams and fires, a place in which we, the tribe, lay ourselves down. Coffinlike, except that we can flatten ourselves in. Like papers, like those lines on paper. The book closing, we live between the pages.” Native peoples as described in obsolete literature and ethnographies, however, survive long after the reader closes the book, as do the injurious images they can engender. Costumed and captive, Barrie’s Tiger Lily thrives in the Indian princess apparel purchased for music festivals and costume parties. The director Sterlin Harjo (Seminole) and the 1491s sketch comedy group offer a takedown of Native impersonators in “I’m an Indian Too,” filmed at the 2011 Santa Fe Indian Market. In Pulley’s story, the tenuous relationship between Tiger Lily and Tinker Bell reveals the fissures between Indigenous and white feminisms. Tiger Lily explains, “She and I are not the same. She can claim not to fly and claim the wings define her too, but no matter, she can remove and grow them back, which is mobility in itself. I’ve nothing to remove, yes. But I’ve nothing to grow back either.”

The story concludes with Tiger Lily’s reflection on language and song. “I can conjure a memory of us speaking a tongue separate from the rest of Neverland,” she states.“ And I can almost hear the inflections and guttural reverberations and I can almost feel my throat as having made these sounds—I could not for a thing in the world think of a single word we had that was our own. . . . Even our songs seemed to be that of only drums—someone’s tune empty of us—and . . . I couldn’t place where the drumsong was housed. Was it one of our hearts or the lands or like the village popping up each morning, was it also handed to us for the purpose of playing it back? Who even played them?” Pulley’s meditation on songs is especially poignant for scholars who make and use recordings of Indigenous music as part of academic research. Ethnographers have recorded thousands of Native songs since 1890, recordings housed in institutional archives. After the 1990 passage of the US Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the return of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, including songs, became an institutional priority. The process of repatriating archival recordings is complex, however, as discussed by Beverley Diamond, Janice Tulk, Judith Gray, Robin R. R. Gray (Ts’msyen), and Trevor Reed (Hopi) in the The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation (Gunderson, Lancefield, and Woods, eds., 2019). Furthermore, institutions cannot always repatriate recordings for various reasons. In such cases, who even plays these songs, indeed?

Waln, Tate, and Pulley effectively unsettle the colonial underpinnings of Peter Pan in challenging ways. Through lyrics and performance, Waln subverts the Disney song, transforming it into an expression of protest. Working collaboratively with a non-Native composer, Tate resigns himself to the unwelcome reality that musical theater involves caricature, but refuses the most egregious musical tropes in the “Ugg-A-Wugg” song. Pulley gives Tiger Lily a voice, empowering her to express complex thoughts and feelings and thereby to reclaim her humanity. In an era of Indigenous resurgence, these artists react to Peter Pan in light of their lived experience as Native peoples who regularly confront racial profiling, overturned treaties, violations of sovereignty and land rights, intergenerational trauma from forced relocations and residential schools, and social invisibility. The calls for political protest and social justice embedded in their work raise awareness about issues Indigenous peoples face on a daily basis.

It can be intimidating for non-Natives to square up to Indigenous arts of resistance, yet Paul Chaat Smith exhorts us “to engage, program, and critique Indian artists,” and acknowledge that “the Indian experience is at the very center of how the world we live in today came to be.” What matters is “whether we can build new understandings of what it means to be human in the twenty-first century. It isn’t about [Native people] talking and [non-Native people] listening. It’s about an engagement that moves our collective understanding forward . . . Good intentions aren’t enough; our circumstances require more critical thinking and less passion, guilt, and victimization.” I sometimes think we should simply relegate Peter Pan to the dusty shelves of institutional archives, relevant only to academics who study social change. On the other hand, unsettling this work through the lens of Indigenous creators can help white people to decolonize ourselves, which is a crucial step toward reconciliation.

I want to thank Dr. Johann Buis and his students at McGill University for an insightful and inspiring discussion; Drs. Tamara Bentley, Lei X Ouyang, Natanya Pulley, and Melinda Russell for helpful feedback; Elizabeth Levine for technical assistance; and the editors of Musicology Now for patience and encouragement.

About the Sounds of Social Justice Roundtable

From Roundtable curator and Musicology Now editorial team member Joan Titus:

We have witnessed significant shifts in the past several years in terms of human and civil rights across the world, and within US politics. Music and sound are inevitably involved in the expressions of positions on these rights and the search for social justice. Pussy Riot’s songs and protests against discrimination, US Americans singing on the streets during protests, social media posts about identity and music by Indigenous Americans, and the revival of past music and civil rights icons, such as Nina Simone, in current popular media all point to civil unrest, and how music and sound are integral to human expression. This Roundtable, “Sounds of Social Justice,” offers a variety of perspectives from scholars and artists on music, sound, and social justice today. Each piece, published over the course of 2021-22, allows us to contemplate how people engage the global concept of social justice through specific cultures and media.

Listen to the previous contribution to this roundtable, “The Language of The Coding” a conversation between Neil Verma and Yvette Janine Jackson.