Speaking and Singing in Beauty: Marianne Faithfull’s Vocal Authority

What makes a voice sound beautiful, or meaningful, or authoritative? And what is at stake for singers when the vocal sounds associated with authority originated from a history of harm? On her most recent album, She Walks in Beauty (2021), singer Marianne Faithfull probes these questions by musically re-imagining the work of canonical romantic poets. When I listen to She Walks in Beauty, I hear Faithfull challenging her listeners to consider the implications of hearing authority in a “damaged” singing or speaking voice.

Since the 1970s, Marianne Faithfull’s work has drawn attention to the way that singing and speaking voices shift and change. Faithfull’s career began in the mid-1960s. Still a teenager, she had had little vocal training, resulting youthful, untutored vocal quality: her tone was not always consistently strong, her breath sometimes shaky, her vibrato uncontrolled. Lynn Gackle, a vocal pedagogue who specializes in adolescent female voices, attributes these qualities to physical changes in young singers’ bodies. For Faithfull, these vocal qualities were not shortcomings. Instead, they gelled nicely with the image that her record label promoted: the image of a feminine ingenue and a paragon of unblemished white girlhood, as explained by popular music and media scholar Norma Coates.

Marianne Faithfull in 1966, performing on the Dutch television program Fanclub. Image from Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision Wiki. Photographer: A. Vente.

Faithfull’s youthful, girlish voice bolstered this image. One press release, quoted by Faithfull in her memoir, summed this up, describing her as a “little seventeen-year-old blonde…who still attends a convent in Reading…she is lissome and lovely with long blonde hair… She is shy, wistful, and waiflike.” Her most well-known recording from this period is “As Tears Go By,” a song written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, in which Faithfull gives voice to those shy, wistful qualities.

Marianne Faithfull performs “As Tears Go By,” recorded ca. 1964.

Perceptions of Faithfull—and of her voice—had shifted by the end of the 1960s. Faithfull had a highly-publicized romantic relationship with Mick Jagger and, in 1967, was with the Stones during a police drug raid. While the Rolling Stones emerged from the legal fallout with a boost to their rock and roll credibility, Faithfull was the target of misogynist backlash in the British press, and rumors flew about her sexual relationships. In her memoir, Faithfull recalls that “the energy that you need to oppose an assault like this is phenomenal. You need a huge amount of psychic stamina just to withstand a pressure as unyielding as that, never mind combating it.” Her mental and physical health suffered in the months that followed but she remained artistically prolific, releasing several singles in 1967, and appearing in numerous films and plays between 1967-1970. But these efforts were often dismissed. Over the next decade, she contended with illness, addiction, and homelessness, leaving behind the carefully constructed ingenue image that her voice had previously evoked.

Faithfull’s 1979 album Broken English represented a re-emergence—and introduced a new voice. Gone was the girlish soprano: years of chronic laryngitis deepened Faithfull’s vocal range and transformed her timbre.

Marianne Faithfull sings the title track from her 1979 album, Broken English.

On “Broken English,” Faithfull’s voice sounds angry, piercing, and focused, crackling when she sings with emotion. In the years that followed, Faithfull experimented with genre and style. Broken English was punk-inspired, in the 1980s and 1990s she recorded albums of cabaret songs, and in her more recent records—Give My Love to London (2014), Negative Capability (2018), and others, she has collaborated with Nick Cave, Lou Reed, and other rock stars with connections to avant-garde music scenes. These collaborations enabled Faithfull to reinventing herself as an art world figure, far removed from the pop star of the 1960s, and enabled her collaborators to draw on her growing cachet as a grande dame of rock.

Faithfull’s voice enabled this shift: she uses vocal sounds that evoke a hard-lived life—hoarseness, breathiness, a range markedly lower than her youthful voice, to claim authority over her own narrative. In her work on the so-called damaged voice, musicologist Laurie Stras writes that we hear disrupted or damaged voices as “a measure of the body’s cumulative experience” that communicate more than the words they speak. Faithfullultimately reinvented herself by using her singing voice to sound out the effects of time and trauma and to assert her musical authority.

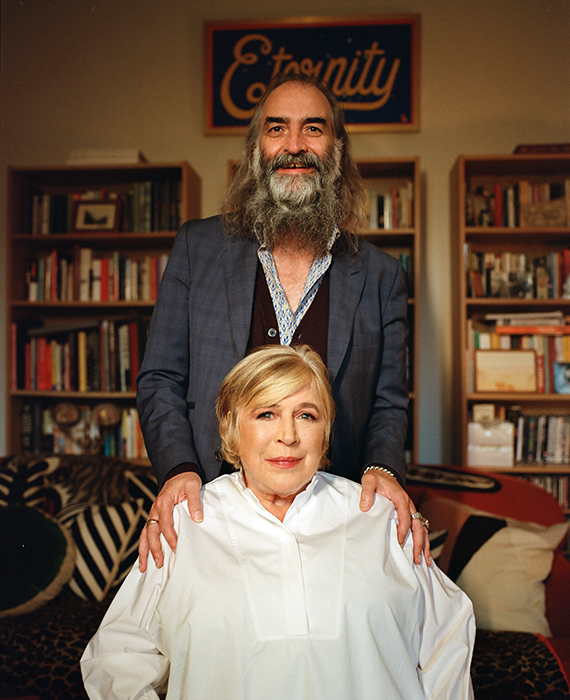

Marianne Faithfull and collaborator Warren Ellis in a promotional image for She Walks in Beauty. Photographer: Rosie Matheson.

She Walks in Beauty, recorded in 2020 and released in April 2021, is the latest of Faithfull’s work in this vein. As a spoken word album that includes no singing, it’s distinctive among Faithfull’s output. The timing of its creation and release in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic is also significant: Faithfull recorded some of her vocals before falling ill with the virus, the rest after her recovery—and COVID may have irrevocably changed her voice. Nominally, the record is Faithfull’s tribute to the British Romantic poets she claims to have admired since her school days, but it is also an album about voice and authority. Faithfull performs poems by Byron, Keats, Tennyson, Shelley, Wordsworth, and others. Given her past, as someone who was shunned by the white British establishment, her engagement with these texts might be understood as an act of vocalizing authority—in this case, by claiming a right to be taken seriously as an interpreter of canonical texts; her lived experience (as communicated through the sound of her voice) can bring new meaning to those texts.

On She Walks in Beauty, Faithfull uses the inflections of a storyteller to illuminate words. On each poem, her voice rises and falls and ebbs and flows almost melodically as she emphasizes words and syllables. Her voice is set to musical tracks that are comprised of washes of reverberant sound and melody. These were composed and arranged by Warren Ellis of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds; Brian Eno created ambient electronic background sounds; and Nick Cave and cellist Vincent Segal contributed instrumental parts. While each poem has a distinct treatment, they share a musical vocabulary. “To the Moon” (Percy Bysshe Shelley), for instance, has an oscillating quality, evocative of shimmering stars. “Belle Dame Sans Merci” (John Keats) opens with relatively sparse electronics, suggestive of the early electronic film score of Forbidden Planet. Still others seem to use electronic sounds to distort non-digital sounds: “The Prelude, Book One” (William Wordsworth) has moments that sound like an old, scratched record being played and amplified. Each track texturally rich, with blurred and indistinct details: layer upon layer of sound, slow moving and overlapping melodic lines, and textures that gradually build and morph leave few moments of silence.

Marianne Faithfull’s performance of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “To the Moon” from She Walks in Beauty.

Because these musical tracks are slow and ambient, the details, small inflections, and bodily sounds that constitute Faithfull’s vocal delivery pop out. Faithfull’s voice (which was recorded by Head, a producer known for his work with singer PJ Harvey) has been recorded so that every small sound is audible: the way she lisps on soft consonants, the way her voice becomes rougher and more gravelly at times, and the sounds of her mouth articulating words with care—sounds of tongue touching teeth and palate. When she speaks, her voice is low and resonant; her speech slow and deliberate, allowing each word and each syllable time to land. Her spoken phrases arc in subtle melodies in response to the meter of the poems.

This is a record that draws attention to the specificity of her voice, and her timbre suggests that that she has particular insight into these texts. This is particularly compelling in her performances of Thomas Hood’s “Bridge of Sighs” and Alfred Tennyson’s “Lady of Shallot,” poems about women dying, which romanticize and idealize feminine pain and sacrifice. Faithfull does not claim to be offering a feminist revision of these texts. However, when I hear them rendered in her voice—a voice very literally shaped by gender-specific experiences of exclusion—I hear her exposing the consequences of romanticizing gendered harm, asserting authority over such narratives, and revealing their ramifications.

This act of giving voice to authority, however powerful, reveals the limited options available to many women pop singers who want to sustain their careers beyond their initial pop popularity. I wonder: is experiencing and then vocalizing trauma and pain their only path to critical credibility? As listeners who admire the kind of narrative authority that a “damaged” voice like Faithfull’s communicates, do we romanticize harm? Moreover, to what extent does Faithfull’s performance resonate because of her unnamed whiteness? Masi Asare, Daphne Brooks, Maureen Mahon, and other scholars of Black women’s vocal performances have reflected on how the voices of singers like Aretha Franklin, Tina Turner, and others are often assumed to be naturally virtuosic and untrained, belying their ingenuity, expertise and authority. She Walks in Beauty moves me to ask whether it is easier for white singers like Faithfull vocalize pain and be taken seriously than it is for singers of color.

Contextualizing She Walks in Beauty in the COVID-19 pandemic also pushes me to consider why we value voices shaped by experiences of pain. As Faithfull has told music critic Alexis Petridis, she expects that, due to the damage COVID-19 caused in her lungs, she may never be able to sing again. She also says that her years of ill-health—which began in the aftermath of the 1960s—likely contributed to the severity of her COVID infection. It is simplistic to draw a line directly from the misogyny that Faithfull experienced in the 1960s to the recent loss of her singing voice. But this vocal loss is one in a series of losses that have ties, both direct and indirect, to how women like Faithfull experienced the rock world. While voicing such experiences may have become a means of claiming authority, She Walks in Beauty asks us to consider what is at risk when we value the vocal sounds of experience.

Many thanks to Sarah Gerk, Rebecca Geoffroy-Schwinden, Jill Rogers, and Kristen Turner for their thoughtful feedback on an early draft of this piece.