Bottom Power Ballad: Troye Sivan’s #BobsBoutBottoming

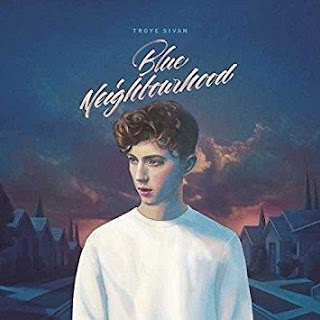

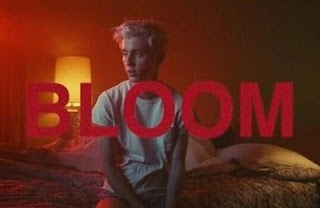

Singer-songwriter, producer, and actor Troye Sivan first made a name for himself in the Land Down Under with a hugely successful YouTube channel. Sivan’s cherub-next-door charm, choirboy voice, self-deprecating humor, and sincerity were a winning combination. His videos racked up millions of hits, and soon Hollywood took notice. Sivan landed a role in the X-men franchise while writing the songs for his debut EP. TRXYE (2014) rose to #5 on the Billboard 200, and his acclaimed full-length studio debut, Blue Neighbourhood (2015), confirmed that Sivan was a rising star to watch. In 2018, he released three singles ahead of his sophomore studio album: MY, MY, MY; THE GOOD SIDE; and the title track, BLOOM.<1>

“Bloom” is what I call a “bottom power ballad.” The punny significance of this term is threefold. First, “bottom” is gay slang for the receptive partner in male-male sexual encounters (“top” describes the penetrative partner). Men on the “bottom” are often stereotyped as passive, effeminate, and powerless, maybe even bent on self-shattering. Second, I’m making a rather obvious pun on the 1980s power ballad, a genre that offers musicians (most often men who otherwise rock) an opportunity to explore their sensitive, and some might say feminine, sides. Musically, however, “Bloom” is not a power ballad but a mid-tempo electronic dance tune. In making a connection between the power ballad and “Bloom,” I draw less from the musical semiotics of the genre than from a discourse that surrounds the power ballad, a discourse that Spin music journalist Charles Aaron characterizes in terms of male vulnerability, humiliation, and shame. Finally, I suspect that Bloom/ “Bloom” can complicate or queer the notion of “bottom power,” a Nigerian turn of phrase used to describe women’s reliance on sex/sexuality to access male power and privilege. I first learned the phrase from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TedTalk, WE SHOULD ALL BE FEMINISTS, and I borrow then playfully misuse it here.

Situating Troye

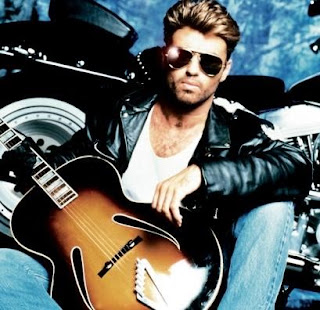

Journalists trumpeted Sivan’s arrival as the harbinger of a new pop era. As The New York Times recently announced, he’s “here, he’s queer, get used to it,” effectively turning a Queer Nation activist slogan from the 1990s into a retro byline for Sivan’s popstar brand. Comparisons to Freddie Mercury, George Michael, Elton John, and Boy George abound; however, such analogies often obscure crucial differences surrounding each man’s status as a gay entertainer. For these older gay men, midcentury homophobia, Reaganism/Thatcherism, and AIDS created a dissonant buzz deep in the mix of their careers. Mercury’s rise to fame overlapped with the Gay Liberation era in the US and the UK, but for a celebrity of his stature, being out was career suicide. Mercury only had to look at Jobriath, the first out star signed to a major label, to see how quickly the stain of queerness in a homophobic culture could destroy a career. He struggled to balance his larger-than-life persona as the front man of one of rock’s most prominent acts with a semblance of normalcy in his life away from Queen. While Mercury played coy with the press about his sexuality, he released a statement just hours before his death in 1991 in which he acknowledged that he was living with AIDS. Notoriously private off-stage, Michael was outed after his 1998 arrest for lewd behavior in a Los Angeles men’s room, though rumors about his sexuality dogged the singer for most of the preceding decade. He occasionally created music about his experiences as a gay man. JESUS TO A CHILD (1996) mourns the death of Michael’s partner, Brazilian designer Anselmo Feleppa (who died of an AIDS-related brain hemorrhage), while OUTSIDE (1998) responds directly to the scandal of his arrest.

A product of the Internet age, Sivan’s coming out was mass-mediated from the start. At eighteen, he seized control of his digital narrative in a coming out video that spoke to millions of LGBTQ kids around the globe. His family has been openly supportive, and his fan base accepted him as a gay man more or less from day one, evidenced by the fact that his covers of songs by Adele and others, which use male love-object pronouns, have been viewed millions of times. In many ways, he has more in common with Rufus Wainwright, whose sexuality has been inscribed on his music, music videos, album art, and both on- and off-stage persona since his 1998 debut, than with Michael, Mercury, or Elton John. Family and fan support does not mean that Sivan is immune to homophobia; nor do I mean to equate some mythical, authentic queerness with adversity in a simplistic way. Nevertheless, it is important to point out some key differences in Sivan’s status as an openly-gay public figure and those who made such openness possible. Whereas journalists gloss over or ignore this history, Sivan himself has done his homework and acknowledges the importance of previous generations of LGBTQ activism in his music video HEAVEN.

That Sivan’s work speaks directly to gay audiences, especially adolescents, is critically important given that LGBTQ youth often turn to media and popular culture, film, and books for guidance—a process that anthropologist Kath Weston calls “tracking the gay imaginary” (255-62). Queer visibility is key to reducing elevated rates of depression, anxiety, self-harming behaviors, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ youth, who also represent the largest number of homeless people under the age of twenty-one. Sivan is helping move the needle. For instance, the BLUE NEIGHBORHOOD trilogy follows a fictional romance between two young men, portrayed by Sivan and model Matthew Eriksson. As of this writing, it has more than 6.8 million views on Sivan’s YouTube channel alone—a remarkable achievement for a young gay artist.

Growing Up Troye

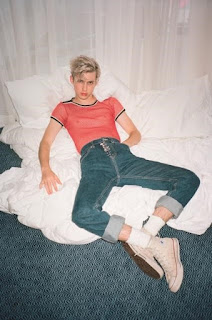

Sivan’s growth from adorable child star to LGBT icon is documented in his social media accounts. In 2007, at age twelve, he began posting videos, mostly covers of songs by others which Sivan sang in his living room. In 2012, he added a vlog and began to connect with other YouTube stars. Sivan’s youthful YouTube persona was beloved for his wide-eyed innocence, prodigious musical ability, and fearlessness in speaking about a variety of personal and political topics. As he matured into late adolescence, his image evolved into that of an erudite, self-deprecating, but widely knowledgeable young man who still had an undeniable cherubic charm. Blue Neighbourhood positions Sivan as a kind of uber-millennial: stylish, somewhat world-weary, yet still possessing his schoolboy innocence. An Australian Rolling Stone review remarked that Sivan “delivers these quiet gems of young wisdom with enough humility to sound endearing.”<2> However, Sivan is not destined to remain a starry-eyed teen idol forever.

Blue Neighbourhood, 2015

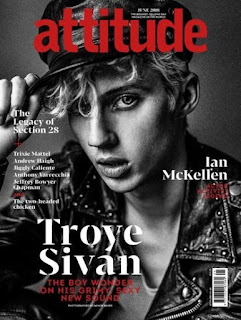

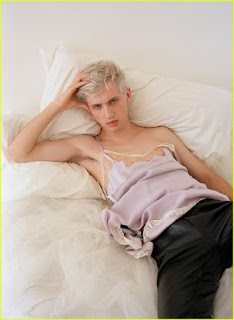

For decades, artsy pop stars have tapped into the potential of an unstable or evolving star text. David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, Elton John, Cher, Madonna, Annie Lennox, and Lady Gaga are all stars for whom reinvention is, or was, a way of life. Notably, many in this list either self-identify as LGBTQ themselves or have devoted queer followings. Likewise, Sivan is revamping his image. From Blue Neighbourhood to Bloom, there’s been a noticeable shift in the iconography of his music videos, photography, live performances, and social media. He made headlines for his appearance at the 2018 Met Gala in New York where he paired androgynous makeup with a sanguine tuxedo and a mesh shirt, and the June 2018 issue of Attitude christens him a “boy wonder” with a “grimy, sexy new sound.”

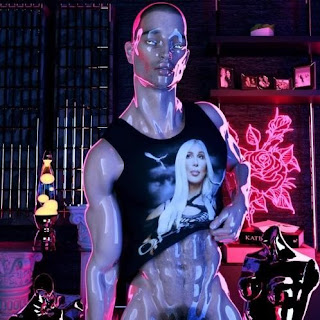

Sivan’s sexy new androgyne image seems to have been inspired by the work of Melbourne-based 3D artist Jason Ebeyer, who created the Bloom lyric video. Taking inspiration from online subcultures, erotica, and technology, Ebeyer’s digital art explores the worlds of light and color as well as darkness and shadow in trippy, shimmering tableaux that blur the boundary between reality and the hallucinogenic world of dreams.

|

| “Earthly Erotica” (2017) |

|

| “Fortune Queen” (2018) |

|

| “Bloom” (2018) |

Liquid surfaces, traditionally beautiful physiques, and overt sexual content signal Sivan’s emergence as a “mature” pop star. Similar techniques have been used by many celebrities, but it is especially common for women in entertainment industries to break with their “innocent” pasts and emerge fully sexual(ized) in order to remain in the game. Britney Spears famously transformed from seductive schoolgirl to outright vixen, and Christina Aguilera shocked with her shift from teen pop princess to “Dirty” superstar. Such changes can be empowering or inspiring for celebrities who wish to move on from their status as child stars to adult entertainers, but feminist critics also argue that this can be a trap. According to media scholar Sut Jhally, women in pop culture face two choices: hypersexualization or obsolescence. Male pop stars have also transitioned from teen idols to music men in this way—though often without the nasty consequences that adhere to women. George Michael, for instance, used macho biker iconography (coded as uber-masculine in straight culture and hypersexual in gay culture) to break with his Day-Glo Wham! past and became a legend.

Attention to his physical appearance dominates discourse about Sivan. In photos, Sivan’s body is frequently positioned in reclined, open positions that feminist media scholars like Jean Kilbourne identify as the stuff of misogyny: bodies shot from above, posed on beds or on the floor, legs spread, inviting the gaze of men, in child-like poses, often infantilized, subjected to dehumanizing violence, and at the same time hypersexualized and always available for sex. Similar images and body positions dominate gay male erotica and pornography, especially in depictions of youthful and inexperienced men (so-called twinks). Journalists frequently remark on Sivan’s “prettiness” and fawn over his flawless, alabaster complexion, which, according to Dazed, “is enough to make you swoon.” Wonderland magazine makes cherubic connections in this video from a 2018 photoshoot. When directed at women, such comments raise the ire of feminist fans and critics who believe that women should be judged by their work and character, not their appearance. Not so for LGBTQ celebrities. While queer activists also promote self-love and discourage body shaming, it’s also routine for journalists and public figures themselves to discuss the importance of beauty, fierceness, and flawlessness as part of twenty-first century queer visibility. This reveals a tension between feminist and queer discourse—and one that this essay will certainly not resolve. That Troye is a cis-male and gay means that he can, in a sense, have his cake and eat it, too. He’s taken seriously in the pop world as a musical force and his “prettiness” serves as an asset.

By contrast, the teaser’s grainy footage and sweat-kissed bodies suggest sleazy pornography and obliquely references the use of similar effects in the intro sequence of George Michael’s OUTSIDE, in which a sexy, “high-heeled saxophone” (5) plays as a man and woman exchange glances and suggestive gestures with one another against a backdrop of blue-green and pink lights. The clip turns out to be a joke; the buxom blonde changes, deus-ex-toilette, into a sternly unsexy policewoman making an arrest. The visual and musical rhymes between the two clips allow me to read Bloom simultaneously as a kind of queer double-voiced utterance, a song of gay innocence and gay experience.

Online speculation about the song’s meaning began immediately, especially around the question of anal sex. Pitchfork described “Boom” as “quite possibly an anthem dedicated to first-time bottoms” and praised the song as “one of the few mainstream pop songs to imagine queer sex as not just a good time, but as something natural, pure, and innocent.” Junkee’s Jules Lefevre concurred. “Let’s be real,” she writes, “this is a straight up ode to being on the receiving end of anal sex for the first time.” Sivan himself was coy when asked to decipher the song. “It’s 100 percent about flowers. That’s all it is,” he told Dazed, adding a playful wink. Contrary to his cheeky denials, Sivan briefly tweeted, then deleted, the hashtag #bopsboutbottoming. Of course, the eagle-eyes of the Cyberland saved the receipts.

As Foucault, Butler, and generations of feminist and queer scholars have demonstrated in well-rehearsed arguments the intimate linkage of sex and power. In white-supremacist, phallocentric, and binary-gender culture, white heterocis men possess the most symbolic, economic, political, institutional, and interpersonal power. They are trained by culture to be top dog, to fight their way to the top, to come out on top, and to stay there. Women can access this kind of power, but as bell hooks points out, its operation remains fundamentally patriarchal. In other words, women with this kind of male power may mistake for liberation what is really just the cross-dressed status quo. Adichie argues that bottom power is illusory because women, lacking their own agency, have only “a good route to tap [a man’s] power.” What happens, she wonders, when he “is in a bad mood, sick, or temporarily impotent?” The implication is that the absence of a sexually-available male from whom she can syphon off some power reduces a woman to powerlessness. While I have critiques of Adichie’s formulation, they are tangential to the mainline of this discussion. Instead, I will ask what happens in male-male sexual culture, where the dynamics of gender-power play out somewhat differently; is there gay-male bottom power; and what happens when the love that dare not speak its name comes out as on bottom on top of mainstream pop?

Bottom Power/ Power Bottom

All gay men risk accusations of being a bottom/effete/powerless, or worse, of enjoying it. That is, they risk being perceived as feminine. The threat of this accusation creates quite a bit of anxiety and no small amount of gender trouble among gay men. Need evidence? Cruise on over to any app that gay men use to find sex/romance and count the number of times you see words like masc only, the hashtag #gaybro, or any number of more subtle ways gay men police their fragile masculinity. In our culture’s wildest homophobic nightmares, gay cisgender men relinquish their macho power when, as Leo Bersani memorably described it, they hoist their “legs high in the air, unable to resist the suicidal ecstasy of being a woman.” (18) Effeminate queer icon and author of The Naked Civil Servant Quentin Crisp once quipped that in Western culture, “there is no sin like being a woman.” From the erastes (adult male) of Classical Antiquity to the total tops of the digital age, “real” men, straight or otherwise, get (it) on (from the) top. Here’s an old joke that Bersani recounts:

The butch number swagger[s] into a bar […] opens his mouth and sounds like a pansy, takes you home, where the first thing you notice is the complete works of Jane Austen, gets you into bed, and—well you know the rest. (14)

An updated version goes something like this: His profile says “total top,” then he shares his private pics. There’s even a campy send up by a trio of drag queens called THAT BOY IS A BOTTOM that makes fun out of this queer cultural conundrum.

Some gay male bottoms have reclaimed their stigmatized identity, breaking the stranglehold of sexism, misogyny, and (internalized) homophobia that equates being penetrated with powerlessness by speaking back in a voice that echoes that chants, shouts, and cries of other marginalized groups who have found strength and intelligibility at the margins. I am tempted to call this phenomenon “bottom power,” but the boundless creative energies of queer sexual culture beat me to the punch. Enter, the power bottom. Another term from the queer lexicon, a power bottom is assertive, unashamed, unapologetic, and (stereo)typically sexually aggressive. Power bottoms range from the fey and ephebian to the ruggedly masculine. A more radical form of an always-already denigrated gay-male stereotype, power bottoms resist the shaming of men who enjoy penetration by daring any potential top to try and keep up. This is a very different use of “bottom power” than that described by Adichie. In her formulation, women savor some fleeting male power which they gain by using sex and sexuality. By contrast, the power bottom possesses male power and privilege which he uses to counter accusations of effeminacy. His sexual voraciousness, stamina, and assertiveness become much-admired assets, not liabilities or limitations.

Flowers in an Intertextual Garden

Which brings us to Sivan’s power bottom ballad. Much of the online chatter about “Bloom” misses the rather obvious fact that Sivan’s song utilizes the most humdrum and obvious imagery. Throughout, the green world serves as a metaphor for sensuality, sexuality, and love. In the chorus, Sivan sings, “I bloom for you,” likening the singing subject’s sexual awakening to a flower opening its petals for the first time (there is no indication that this song is, or is not autobiographical). While Sivan’s choice of imagery may be banal, it’s planted in fertile soil. This fairly standard muso-poetic language has a longstanding association with the feminine (Mother Earth), female genitalia (the art of Georgia O’Keefe), and sexuality more generally (Shakespeare even got in on the game in Sonnet 18). These works create a complex intertextual web for “Bloom,” one that extends to vernacular and concert music as well. A few examples, chosen more or less at random, illustrate the use of flower imagery in different song contexts:

- Schumann’s setting of Heine’s “Du bist wie eine Blume” uses the image of a flower to describe the beauty of a beloved, and the composer’s romantic music imbues the idyllic imagery with an intense yearning that borders on the sexual.

- Delibes’ “Flower Duet” (“Duo des fleurs/ Sous le dôme épais”) from Lakmé is a duet for two women in which the voices move in sensual parallel motion as they sing of a “thick dome of jasmine” beneath which “the rose […] blends with the rose” and drifting downriver together.

- In popular music, Liz Phair’s “Flower” (which was covered by homocore band Pansy Division) reverses the gender association of flora with the feminine. To a male lover, Phair/ Pansy Division sing “Your face reminds of a flower/kind of like you’re underwater/ hair’s too long and in your eyes/ your lips are perfect ‘suck me’ size.”

Checking Troye’s Privilege