Harnessing the power of sound and music to inspire positive ecological action.

In the summer 2011 edition of JAMS, Ralph P. Locke ruminates on what he describes as musicology’s recent concern with the idea that music exists ”in and for a ‘community’ of practitioners and listeners.” As an example, the journal dedicates its discussion section to a series of short pieces that address community in the emerging field of “ecomusicology.” Aaron Allen defines ecomusicology as a “socially engaged” musicology that studies “musical and sonic issues . . . as they relate to ecology and the environment;” it is a form of ecocriticism, a field that studies cultural products (music, film, text), “that imagine and portray human-environment relationships.” This essay looks at one such product, Tree People, a 45-minute documentary film I made that portrays the efforts of a local community-based group to plant trees in the valley they live in and, as much as image, uses music and creative sound design to not only convey its message, but to give life to the audience’s imagination. The film is part of my on-going research as a composer of acoustic and electronic music, filmmaker and writer, investigating the use of sound and music in documentary film. This has resulted in several solo and joint film productions (with Keith Marley) since 2000. The work focuses on how sound, especially creatively treated, can be a powerfully emotive signifier in documentary, perhaps even more so than image, and thus emphasises the potential of the form’s aesthetic aspect.

If concerns about the environment fuelled interest in ecomusicology in 2011, then in 2019 such concerns have reached fever pitch. As I write, France has just recorded its hottest ever temperature of 45.9°C and a recent report suggested that, due to climate change, it is “highly likely” that human civilisation will come to an end in 2050. Meanwhile, in April, environmental protest activists, Extinction Rebellion, staged “die-ins” across the globe (and continue to do so), highlighting this all-too-serious doomsday scenario. Such events and research often lead to the couching of ecologically-focussed literature and film in what Alexander Rehding describes as ”apocalyptic” terms: “this orientation toward crisis makes sense, as it endows the literary products with political relevance, powerful realism, and—in a very literal sense—sublime terror. The earth needs to be saved, right now.” Timothy Clarke asserts the value of ecocriticism with a similar call to arms: “the new artistic and critical task is to make ‘real’ or make felt on the human scale all these alarming but also boring statistics on the planet’s condition.” The problem with such approaches, understandable as they are, is that, instead of serving as calls to action, they lead to a hopeless inertia, since the enormity of the task makes personal and individual action seem fruitless while also engendering fearful paralysis. Communication strategist Nicky Hawkins suggested recently that “we’re stuck in a climate disaster movie—and it’s not even a very good one… Our response is predictable: we switch off.” Instead we should move on from “chastisement and detachment” and focus on stories that suggest possible ways to save our planet, telling and retelling them “in ever more interesting and inspiring ways.” Tree People adopts this approach, appealing to the power of hope and memory, since ecological action is often driven by the nostalgic imagination and, as Hawkins suggests, stories of real and inspiring efforts to make change. In the service of such positive ecological consciousness-raising, the penetrating, enveloping presence of sound and its capacity to almost “touch” us only to explode a multitude of responses, is an all-important tool. Motivation to act positively (or even act at all) in the face of such daunting events and predictions requires something more than information and “instruction;” it needs a positive, emotive, even transcendental power, and as Steven Connor has said, sound comes towards us such that “we cannot listen without taking into ourselves the sounds we hear” and so has a very real physical power, while remaining “mysterious.” It is, of course, the ineffable power of musical sound that can potentially “move, shake and touch us” most of all.

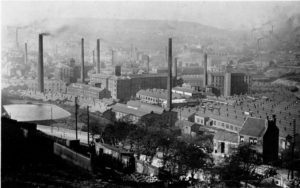

Tree People’s account of 50 years of tree-planting by the Colne Valley Tree Society (CVTS)—at the edge of the wild Pennine moors, West Yorkshire, in the north of England—and the consequent transformation of a once relatively barren and scarred post-industrial landscape is a positive story. It reveals and charts the change to a quite heavily wooded valley in its lower reaches, and a lush “green lung” for its increasingly densely-populated surroundings. Though not explicit in the film and not part of the original vision of CVTS, tree planting is now widely recognised as helping in atmospheric carbon dioxide reduction—recent research suggests that it is “by far the biggest and cheapest way to tackle the climate crisis.” The film draws on nostalgic memories of the valley’s vibrant industrial past, of the teeming, smoke spewing woollen mills (early carbon dioxide contributors of course) and bustling villages, but also on the pre-industrial era in which myth has it that a squirrel could travel the seven miles down the valley, leaping from branch to branch without touching the ground. The film’s focus is on the natural landscape, planters’ testimony, society history and actual tree planting activities. It shows that though the laying to waste of woodland in the industrial revolution put paid to the squirrel’s journey, concerted, long-term and completely voluntary effort in planting 400,000 trees since 1964, has made it almost a possibility again.

Documentary film has many modes, from propaganda to “factual” to impressionistic, from didactic mainstream, to art-house experimentation. Though wedded to truth-telling, Tree People is, in a sense, propaganda—a celebration, even—but its mode is largely impressionistic, with music and sound playing a prominent functional role. Its basis is not in telling but in showing and making the viewer feel something, as much as understanding it. As far back as the 1930s, in documentary films like Night Mail (1936), with its score by a young Benjamin Britten and poetry by W. H. Auden, pioneers like John Grierson realised the power of artistically-driven evocation aided by the use of music, rather than word-heavy “telling.” Also drawing upon Auden, Coal Face (1935) goes beyond conventional music in its depiction of coal mining in Britain, with Britten scoring an ensemble of noise-making instruments to mimic and enhance on-screen events. I have written how this foreshadows, both practically and theoretically, Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète, where a sound’s source becomes secondary, or even irrelevant, to the timbral aesthetics of the sounding “object” itself. In the 1960s, promotional films about Scottish industry continued this tradition. Scores were commissioned by the likes of Iain Hamilton and Frank Spedding and, in a series of later edits, Grierson reduced the footage of films like Seawards the Great Ships (1960) and The Heart of Scotland (1962) to image and music alone. For him, the “magic” of documentary is not in its discussion and verbal instruction but in its aesthetic capacity to inform and inspire through appealing to what he described as the “imaginative life of the people.” The way the music of Hamilton and Spedding (and intriguingly, the services of Alfred Hitchcock) are used to this end is discussed in my article on the output of Films of Scotland. This musicological research into the highways and byways of the British documentary movement has had a deep influence on my own practice. Beyond Tree People, Mill Study (Cox and Marley, 2017), is a short film also made in Colne Valley about Spa Mill, one of its few surviving woollen mills, which aided by spoken poetry by Andrew MacMillan, explores its sights and sounds.

Milnsbridge, Colne Valley, 1930s. Very few woollen mills are active today.

Tree People strikes a balance between informing the viewer and inspiring them through artistic representation, driven by sound and music. The balance between more conventional exposition and artistic expression was a fine one to strike and quite subtle audiovisual manipulation proved very important in creating convincing juxtapositions and a satisfying temporal flow. The sonic strategies employed proved especially important and range from traditionally scored music (piano, and brass band), to electronic drones derived from piano string resonances; from vocal fragments naming tree species and locations (taken from participant interviews) randomly manipulated by complex software processes, to location recordings employed as much in the spirit of musique concrète, as realistic depictions of the events and environments seen. The sounds’ functions are multiple: the conjuring of a sense of place by location recordings, and musical contours that mimic the hilly landscape, recorded by Slaithwaite Brass Band in a band room overlooking the valley; the suggestion of the longevity of the planters’ task, the evoking of the slow growth of trees and the momentous history of the valley, by extended atmospheric drones; and the poetic abstraction of the spoken word by the erratically rhythmic naming of trees and places. Even the interviews to camera with the tree planters themselves are chosen and juxtaposed with a musical sensibility and attention given to complimentary vocal timbres, accent, and in the case of an archive recording, the nostalgic grain of the recording medium itself. By the end of the film, the story of the Society and its efforts is told and hopefully understood, but the lasting impression is engendered by sound, as much as image—sound that encompasses commemorative and relatively accessible music, as well as cutting-edge electronic abstraction and the affective grain of the voice, its penetrative powers engaging the audience in an emotive rather than cognitive sense.

The film seeks a local as well as an international audience, its themes both parochial and outward-looking in its search to find the universal in the particular. In ecomusicological terms, as Rehding suggests, “the commemorative and community-building powers of music in the service of ecological approaches, offer exciting prospects” and the use of a local brass band in the score is aimed at such community building and commemoration. The sound of the band also inspires the nostalgic imagination: Slaithwaite Band, formed as a wind band in 1819, was probably the first in the area and has been in continuous operation ever since. It is thus a living tradition and joins the electronic and abstract timbres and software-driven techniques that speak more to worldwide contemporary musical creation, in uniting past and present to offer a positive ecological vision of the future. The slowly evolving main brass theme that occurs at the midpoint of the film (and played on piano only at the start), suggests a dirge-like doggedness, rooted in the past. But its searching, restless harmonies, dramatic dynamic shifts and gradually increasingly dense and dissonant textures suggest forward if slightly unsettling motion: this is not just about what has been but what is continuing and what will be—an increasingly wooded and verdant landscape.

Media researcher John Corner has spoken about how sound and music in documentary can help “connect knowing to feeling and hearing to viewing” as part of the “continuing exploration of the role of art in the quest for understanding,” suggesting that “knowing” is not simply found via information, generally conveyed through words, but that such felt understanding can be gained through emotional connection conveyed in artistic terms. Tree People strikes a balance between Corner’s idea of documentary’s capacity to be “sensual and intellectual, referentially committed yet often possessed of a dreamlike potential for the indirectly suggestive and associative,” Grierson’s desire to tap into the “magic” of the “imaginative life of the people” and Hawkins’ call in the time of climate crisis, for “stories that bring to life our capacity to dream big and get things done.” Trees take a long time to grow so the endeavours of CVTS’s past are only now becoming fully apparent. The film emphasises these visionary pioneers but also the continuing autonomous, voluntary effort, working outside of any official bodies, and shows what can be achieved in this way.

For a more detailed exposition of Tree People see ‘Planting Sounds: re-framing the acoustic environment in Tree People (2014), the story of the Colne Valley Tree Society’