Hildegard’s Cosmic Egg

by Margot Fassler and Christian Jara

NOTE: Margot Fassler, Keough-Hesburgh Professor of Music History and Liturgy at the University of Notre Dame, will present the second annual President’s Endowed Plenary Lecture at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Musicological Society in November. Fassler’s topic is “Hildegard’s Cosmos and Its Music: Making a Digital Model for the Modern Planetarium.” The lecture takes place Thursday, November 6, 2014, from 5:30 to 6:30 pm in the Crystal Ballroom of the Hilton Milwaukee City Center, 509 W. Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The public is invited.

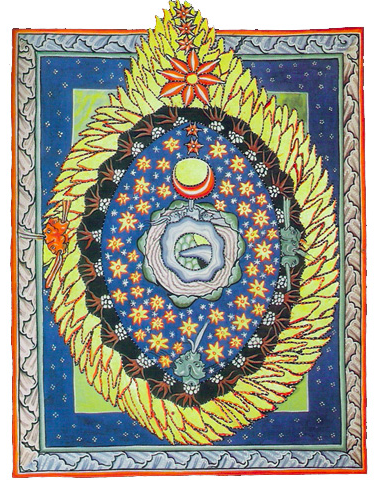

The egg that appears in a vision to Hildegard of Bingen is a post-Lapsarian, post-Incarnational model of the cosmos, but foundational to it are astronomical understandings Hildegard would have found in contemporary treatises, charts, and wind diagrams. This digital model of the creation and cosmos is being made by Christian Jara and Margot Fassler at the University of Notre Dame. It unfolds in two acts, the first of which will be previewed at the Milwaukee national meeting of the American Musicological Society in the course of Fassler’s plenary lecture. This act depicts the dramatic events of creation—a big bang in slow motion—including the separation of light from darkness and the calling to life of the angelic hosts, and the formation of the earth. This introduction will be followed by act II, a moving three-dimensional model of the cosmos, with zoomable features. Both acts are accompanied by music composed by Hildegard, and sung by students from the Program in Sacred Music at Notre Dame, conducted by Professor Carmen-Helena Tellez. The nuns of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Hildegard, Eibingen (Rüdesheim, Germany), have generously made available the high resolution images used in creating the model, and animated versions of some of them will be featured in the talk.

The complete model with music will be unveiled in Notre Dame’s Digital Visualization Theater on March 12, 2015, at the annual meeting of the Medieval Academy of America.

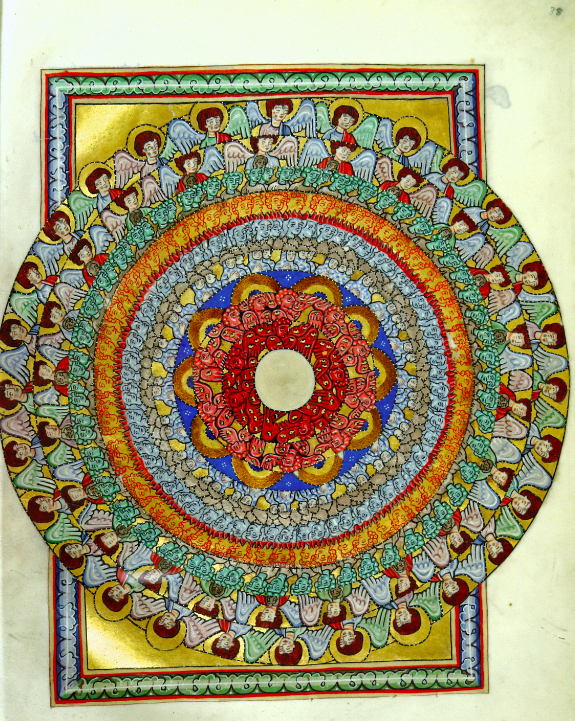

Scivias II.i and Scivias I.vi are the images underlying the presentation in Milwaukee, and both are copies made in the 1920s by the nuns of Eibigen from the now-lost original, Wiesbaden 1. The software we use at Notre Dame allows us to work together, scholar and digital modeler, to turn flat images into moving three-dimensional displays, and to add the music that Hildegard composed as she thought about the stages of creation under discussion. Scivias I.vi is a depiction of the heavenly hosts, the nine ranks of angels.

We will move the image into the dome of the planetarium and spin the ranks in one by one, to the music of Hildegard’s antiphon for the angels, “O Gloriossimi.”

According to Hildegard’s understanding of Genesis I, the angels were created first as they are pure light. The light that surrounds the cosmos makes it appear like a fiery globe, and we will make it permeable to the entire structure can be zoomed into, revealing its features, and allowing for deeper understanding of the cosmos to a twelfth-century theologian, scientist, and composer—and Hildegard was all three.

We are now creating various test models of the fiery shell of the universe, and you will see some at the AMS lecture, with appropriate music. The image of the cosmic egg from Scivias I.iii circulates widely on the internet. But because we have the high-resolution photographs, lent by the nuns of Eibingen, who retain the rights to them and who own the original manuscript, we are able to incorporate details that would otherwise not be available. The images below are, first, from the internet, and, second, a blowup of the edge of the image in high resolution.

Preparing sounding, digital images from medieval manuscripts and studying the music that relates provides the researcher with ideas based on new evidence. We think we know how the images were made, and the degree to which Hildegard thought through and with them as she composed her music and her liturgical poetry.

When available, Musicology Now will co-publish with the Medieval Institute at Notre Dame a video trailer with moving images.

Margot Fassler‘s faculty webpage at Notre Dame is HERE. Christian Jara is a digital artist affiliated with Notre Dame’s Center for Creative Computing.