Inheriting Ivalice: The Multiple Sonic Legacies of Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age

By Ryan Thompson

Final Fantasy XII was originally released in 2006 for the Playstation 2, and a remastered edition was released in 2017 for the Playstation 4 under the title Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age. It may seem strange for a remastered video game to be among the biggest releases of the summer season; by way of explanation, when the game was originally released, North American and European audiences received versions of the game lacking many additional features that would make their way into a Japanese special edition.[1] As a result, many players are experiencing the final version of the game for the first time. In addition to being part of the well-known Final Fantasy franchise (as popular in gaming as Star Wars is in the cinema), the game is the inheritor of two additional, important gaming legacies, each of which I’ll touch on briefly as I set the stage for essays to follow. Understanding all of these various influences upon Final Fantasy XII and its score is vital to understanding why the score for the game appears to depart from long-standing franchise traditions in myriad ways.

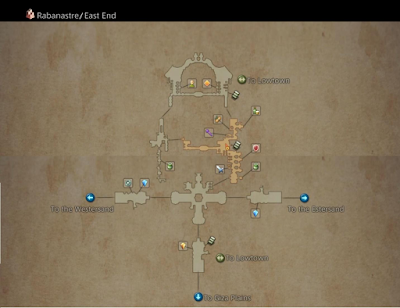

Playing Final Fantasy XII reveals that despite a return to more traditional JRPG design, the game owes much to the MMORPG stylings of Final Fantasy XI.[5] Ivalice, the fictional world in which Final Fantasy XII takes place, is built on a massive scale compared to anything in FFX, and often feels like a conversion of an MMORPG back into a single player experience. Figure 1, below, shows the map of Rabanastre, the first city the player encounters (and one of the largest).[6] To give a firmer sense of the scale at hand, Figure 2 shows the player’s view from the location marked on the map (on the right side, in the city’s main shopping district). Rabanastre is populated (see Figure 2) with dozens of non-player characters (NPCs) that serve only to give the player the illusion of a bustling city, such as the towns in MMORPGs in which hundreds of players exist simultaneously.

|

| Figure 1. Map of Rabanastre. Screen capture by author. |

|

| Figure 2. City of Rabanastre, market district. Screen capture by author. |

This sense of scale holds true in the audio also, in which the melody line is passed among many different instruments – a rarity for town themes in the franchise that makes the player feel like they are only a single part of something much larger. By way of comparison, the largest town in Final Fantasy X and Final Fantasy X-2, Luca, is scored very differently. In both games the timbres change far less often and are far less varied, maintaining a focus on the player characters and their actions instead of the town itself.

Rabanastre’s music:

Contrasting Final Fantasy XII with Final Fantasy X and its direct sequel, Final Fantasy X-2 (so numbered because unlike most entries in the franchise, it contains the same characters and environments as FFX) serves as a reminder of the other legacy that Final Fantasy XII carries forth. It’s a sequel not merely to the mainline Final Fantasy franchise, but to a series of connected games that was re-branded as the “Ivalice Alliance” upon the release of Final Fantasy XII in 2006.[7] As previously mentioned, Ivalice is the fictional world in which the game takes place; the location was originally created as a fictional world for the fan-favorite Final Fantasy Tactics – a spinoff game from the main franchise that, without devolving to a discussion of game mechanics, was not a numbered entry because it is a “tactical RPG” more in common with franchises like Disgaea and Fire Emblem than JRPG staples such as Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest.

Ivalice is an explicitly Western-European fictional world, a land of Arthurian swords and sorcery. When discussing individual themes above, I mentioned a variation of timbres – when we broaden our gaze to examine the soundtrack as a whole, we instead see a lack of variety in orchestration. Nearly every track is scored for orchestra, when in previous Final Fantasy games (I’ll again reference Final Fantasy X, but this holds true for much of the franchise) we tend to see at least two major instrumental groupings, one of which includes a rock ensemble. This lack of variation in the orchestration makes clear the deep dive into Western culture that Ivalice invites, especially when compared to the clearly faux-Okinawan setting of Final Fantasy X’s Spira or the Japanese pop-stylings of Final Fantasy X-2.

Similarly, this is reflected in the visual design of the game as well. Without spending significant time discussing the graphics, it bears mention that FFX features clearly Japanese / Okinawan characters and locales, while every character in FFXII features aspects of a European / Arthurian knight’s armor, and every location in Ivalice is some variant of Tolkienesque fantasy instead – with Ivalice’s viera substituting for Tolkien’s elves.

Players shouldn’t assume the soundtrack is disconnected from the franchise writ-large by any means – the final boss theme, “Struggle for Freedom,” quotes “A Presentiment” from the score to Final Fantasy V in dramatic fashion sure to raise the ears of players who recognize the quotation.[8]

|

| Figure 3. Transcription of “Struggle for Freedom” quoting “A Presentiment” at 0:43 by author. Performance markings approximate rubato by conductor in recording. |

Overall, the soundtrack to Final Fantasy XII is part of the legacy of the Ivalice Alliance much more than it is indebted to Nobuo Uematsu’s work on the first ten Final Fantasy games. It bears mention that this decision may have much to do with Uematsu’s departure from the franchise: with the exception of “Kiss Me Goodbye,” the song that plays over the end credits, Uematsu did not write any of the soundtrack to Final Fantasy XII, with compositional duties instead taken up by Hitoshi Sakimoto – by no coincidence, the composer for Final Fantasy Tactics, the first Ivalice Alliance game.

It’s possible to enjoy Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age without any of this knowledge, of course. Similarly, it’s easy to dismiss many of the steps away from the franchise’s established musical traditions as merely the result of a different composer. Knowing that the game functions not only as a sequel to Final Fantasy X, but also as both a conversion of the MMORPG experience to a single player format and a continuation of the mythos created for Final Fantasy Tactics, provides deeper context for why the soundtrack to the game differs so greatly from prior entries in the franchise.

Ryan Thompson is a Ph.D Candidate in Musicology at the University of Minnesota. His nearly-completed dissertation focuses on the interactions between game audio and gameplay; specifically, instances in which listening actively improves a player’s ability to play a given game. He has presented at AMS Midwest, the North American Conference on Video Game Music, Music and the Moving Image, and the Game Developer’s Conference, in addition to a variety of public-facing scholarship, including an interview with Minnesota Public Radio, a profile for Game Informer, and published articles commissioned for Polygon and The Rift Herald. He can be reached online at @BardicKnowledge.

[1] This was true of all of the big Square Enix titles on Playstation 2: Final Fantasy X, Final Fantasy X-2, Kingdom Hearts, and Kingdom Hearts II in addition to Final Fantasy XII.

[2] This game bears the unusual ten-two name because it is a direct sequel to Final Fantasy X, with the same characters and the same fictional world — at the time, a first for the franchise.

[3] It bears mention that because it’s so different from the others, Final Fantasy XI (and FFXIV, for the same reasons) is usually not counted in lists of Final Fantasy games, hence its special mention here.

[4] The JRPG genre has often been compared to cinema and theater. See an NPR interview with the author understanding Final Fantasy VI in terms of opera and theater here.

[5] This includes a number of the game’s mechanics surrounding combat, which I leave aside here. Forthcoming posts in this essay series will dive deeper into this topic.

[6] Figure 1 is comprised of two different screen captures edited together – the town is so large that even the map of it won’t fit on a single screen!

[7] Before the original release of Final Fantasy XII, this included Final Fantasy Tactics and Vagrant Story on the original Playstation, and Final Fantasy Tactics Advance (not a port of FFT) on the Game Boy Advance.

[8] It bears mention here that “A Presentiment” is in Bb minor on the soundtrack to Final Fantasy V, and the quotation from FFXII is in C minor, as transcribed.