Lessons from the Archive: On Creativity, Process, and the Working Life of John Adams

None of us is entirely sure what lures us to the creative act—or to studying it, for that matter. For some, it’s the quiet of being alone with raw materials and shaping them into something to give back to a community. For others, it’s the unknown, the chance to navigate unexplored terrain. There’s a flurry of pressure and risk, the thrill of the search, the understanding that success is uncertain. The inner noise can be chaotic. Even the physical labor of transcribing sketch after sketch can take a toll on the hand. Once a draft is completed or a premiere carried out, the mind can rest, it seems. But just as often, the messy processes that precede the product deny perfect resolution. The noise persists, the labor of writing and re-writing continues, the creative act remains unresolved. But in this restless space of revision, the best ideas evolve.

When I arrived for the first time at John Adams’s home in the hills of Berkeley, CA, the composer greeted me with a nervous smile and introduced me to his dog, Eloise. He had spent the early part of that morning revising The Gospel According to the Other Mary (2012), a work whose premiere had taken place seven months prior, but one that required some re-writing for its next performance the following month. His deadline was that day. He led me to his dining room, where several large boxes labeled “Doctor Atomic” rested on the sprawling table. He had grabbed them from his storage unit in Emeryville the day before. “Let me go through to see if there’s anything personal in here,” Adams said as he opened one of the boxes. There was virtually no order to the contents. “These are the sketchbooks, and here’s Peter Sellars’s various libretto drafts. Those are probably worth looking at. Oh, this is pretty juicy. This is classified stuff from I don’t know where. Here’s my application to the Library of Congress when I was looking for recordings for the finale.” He then flipped through one of his sketchbooks and found the first sketch for what became his celebrated setting of John Donne’s “Batter My Heart, Three Person’d God.” “I don’t know how interesting this is because it’s basically the grunt work,” Adams said, referring to his scrawl: a descending chord progression and a two-note sighing figure that repeats in a rising stepwise pattern. “Take your time. Stay as long as you like. I’ll be upstairs if you have any questions.” He then disappeared to work on the Other Mary revisions, leaving me to sink or swim in a sea of disordered documents.

As an aspiring musicologist at the start of a PhD dissertation, I was in a privileged position, faced with a trove of material that not only fulfilled the requisites of a satisfactory dissertation topic, but also seemed to contain the promise of insights about Adams and his music reachable in no other way. But I was in over my head. Beyond the immediate, if formidable, task of cataloguing and making some sense of chronology were more complicated questions about the issues at stake, assumptions to evaluate, and the basic goals of this type of research. Then there were the problems of working with a living composer. Maintaining critical distance would be the big one. Moreover, sensitivities continued to surround works like The Death of Klinghoffer (1991). What was off limits? (Adams had not said whether anything in the Doctor Atomic box was in fact “personal.” How would I identify it as such?) How much would off-limits material (if I happened to see it) inform my broader view of the composer and his process? It was slippery territory. I knew I wanted to approach it carefully, with integrity and respect.

On the surface, the objectivity of philological source studies seemed like a safe entry point into Adams’s compositional life, a way to ostensibly the complications of working with a living archive. Sketch research has always been one of the most technical and esoteric subcultures of the musicological discipline. Compositional sketches are remarkable tools for establishing chronology, reconstructing manuscripts, or identifying unfinished works. They can also help us understand the complexities of the creative process and offer support for preexisting analytical insights or stimulus for new ones. The goals of modern sketch studies, developed through painstaking work on Beethoven’s sketchbooks (perhaps the most fragmented and scattered of all compositional traces), have been reexamined over the years. Technical problems of transcription and dating can be resolved (systematic analysis of watermarks and frayed edges, for example, offer one way to assess chronology). But, as Douglas Johnson admitted in the late 1970s, basic questions will always remain about the relevance of a composer’s preliminary or discarded sketches. In what way could (or should) observations about a composer’s choices, hesitations, and discoveries inform the larger view of not only a completed work but also an individual’s creative life?

In the case of Adams, the distinction between draft and completed work is particularly blurry. Klinghoffer, for instance, has seen multiple compositional revisions since its 1991 premiere. Adams, to this day, continues to adjust his scores in response to performer feedback and other internal and external pressures. Although most of his music is in print, definitive editions have not really coalesced yet, a fact that makes critical comparison of “the drafts” and “the finished work” seem premature. (How can one privilege what the Germans call die Fassung letzter Hand—the composer’s “last word”—if the composer is still around, still mulling over changes?) The positivist orientation of sketch research, while enabling a strong technical grounding, seemed to limit, if not displace, necessary discussion of politically and emotionally charged collaborations, not to mention the immense reception histories of works like Klinghoffer. This project was going to require a mode of critical reflection and analytical rigor that could speak somehow to the technical aspects of the sketches and music, as well as to the moral, political, and collaborative imperatives of Adams’s creative enterprise. The only way to uncover that mode was through determined immersion into the materials themselves.

After a period of delicate negotiation, Adams generously granted me access to his entire archive. For the rest of my graduate career, I looked at upwards of 6,000 documents: diaries, letters, research notes, sketches, autographs, revisions, and more. The materials shed light on both the creative act in the moment, as a kind of snapshot, and a broader evolution of Adams’s working habits over time. Sketches from the 1980s, for instance, find him wrestling with his academic heritage and the limits of musical minimalism. Voluminous material for each opera documents his search for informed responses to sensitive, often contentious passages of recent history. Journals and letters reveal insight into the working relationship between Adams, director Peter Sellars, and librettist Alice Goodman, and how they together sought to recover opera’s potential to meditate on living history.

|

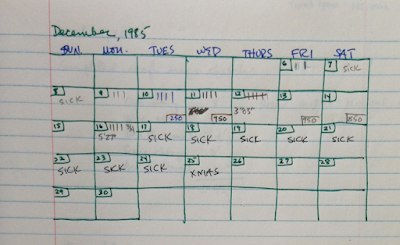

| John Adams, calendar charting initial progress on Nixon in China (December 1985) |

Adams rarely dated his sketches or offered explicit clues about his creative motives on the page. Our conversations about specific documents or the sequence of compositional events filled in some necessary gaps. But it is within the pages of his date-stamped journals that the most vital information about chronology and the composer’s experience emerges. For example, a hand-written calendar found in one of Adams’s notebooks shows that he began composing Nixon in China on December 6, 1985. With a rigid series of milestones to hit and less than two years until the scheduled October 1987 premiere, he immediately took up a rigorous work schedule, duly logging the number of pages drafted per day with hash marks. Anyone who has ever attempted to turn the creative process into a 9-to-5 job will likely identify with this quite literally mundane document, in which the 38-year-old composer notes every sick day and then gives himself a Christmas break. But this doggedness takes on larger musicological significance when juxtaposed with circumstantial evidence gleaned from the composer’s journals. Just before Nixon, Adams had wrestled with an eighteen-month impasse, a period of wandering and lack of focus that would ultimately lead to the compositional breakthrough of Harmonielehre (1984-85). Finishing Harmonielehre, he discovered a harmonic technique and new sound that would drive the writing of Nixon; he also learned that nothing but a fixed deadline would urge him to action. “I sat down one day and wrote Nixon in China at the top of a blank page of score,” Adams recalled in 1988 to Andrew Porter in the new-music magazine Tempo. “I figured that if I didn’t I’d never be able to write the opera.”

So what do we gain from looking over a composer’s shoulder in this way? Most obviously, it expands our sense of what a human can create, setbacks and all. Perhaps it confirms what we already know about work ethic: a period of tireless searching, with failed attempts along the way, can lead to clarity. It’s all about the process, and, judging by the hash marks, the process can be messy. For Adams, the process has been ongoing. In 2009, twenty-two years after the premiere of Nixon, he returned once again to the score to fix unplayable parts and update synthesizer patches. Doctor Atomic, in its turn, has undergone numerous changes since its 2005 premiere, and Adams intends to rewrite portions of the opera for future productions. His continuing revisions keep his works a part of an ever-evolving musical chronicle, one that, in a sense, shares the flux of contemporary history, with implications stretching from the present into the future. This provisional ethos is central to understanding Adams’s stage works. It’s also central to the nature of researching a living composer.

As the Bay breeze drifted in and out of Adams’s dining room that first day at his home, the blinds gently ticking against the frame of the open window, I stood over the stacks of material and hurriedly set to work. Moving through page after page, I made a detailed record of the contents and photographed, with Adams’s permission, select items: Goodman’s original Doctor Atomic synopsis, Act I sketches, post-premiere revisions, and pages from a notebook the composer had kept while writing On the Transmigration of Souls (2002). Later, back at Princeton, I spent my days absorbed in transcription, keeping a journal of reflections and my own hash marks recording pages transcribed. Over many months of observing the traces of an artist at work, an important, if humbling, observation gradually came into focus. Just as Adams’s scores and creative processes continue to evolve, so too must the critical modes and goals of this type of scholarship as it attempts to make sense of a musical life that, at least for now, defies closure. Of course, there is an explicit distinction between Adams’s creative pursuits and those of academic work. But what they share, namely the challenge of finding ways to assimilate living subjects into a larger frame, is equally stimulating, inviting us to listen to the music within the space of its possibilities.

Alice Miller Cotter completed her PhD in musicology at Princeton University in 2016. She currently teaches in the Department of Music at the University of California, Berkeley.