Melodyne’s Nature

When the German software company Celemony premiered the first market-ready version of Melodyne at the North American Music Merchants (NAMM) conference in Anaheim, California, in 2000, music software buyers and enthusiasts responded to the product tepidly, and with a bit of confusion. Melodyne’s engineering team had envisioned and designed the software as a composition-revolutionizing tool, but did not account for questions like “how does this fit into my workflow?” or “how will this interact with my digital audio workstation?” Even less anticipated than those questions was the way the user community would take up Melodyne in the coming years. When audio engineers figured out that it could be used as a pitch correction tool in vocal production, it would eventually become one of the most popular and widely used music production softwares globally.

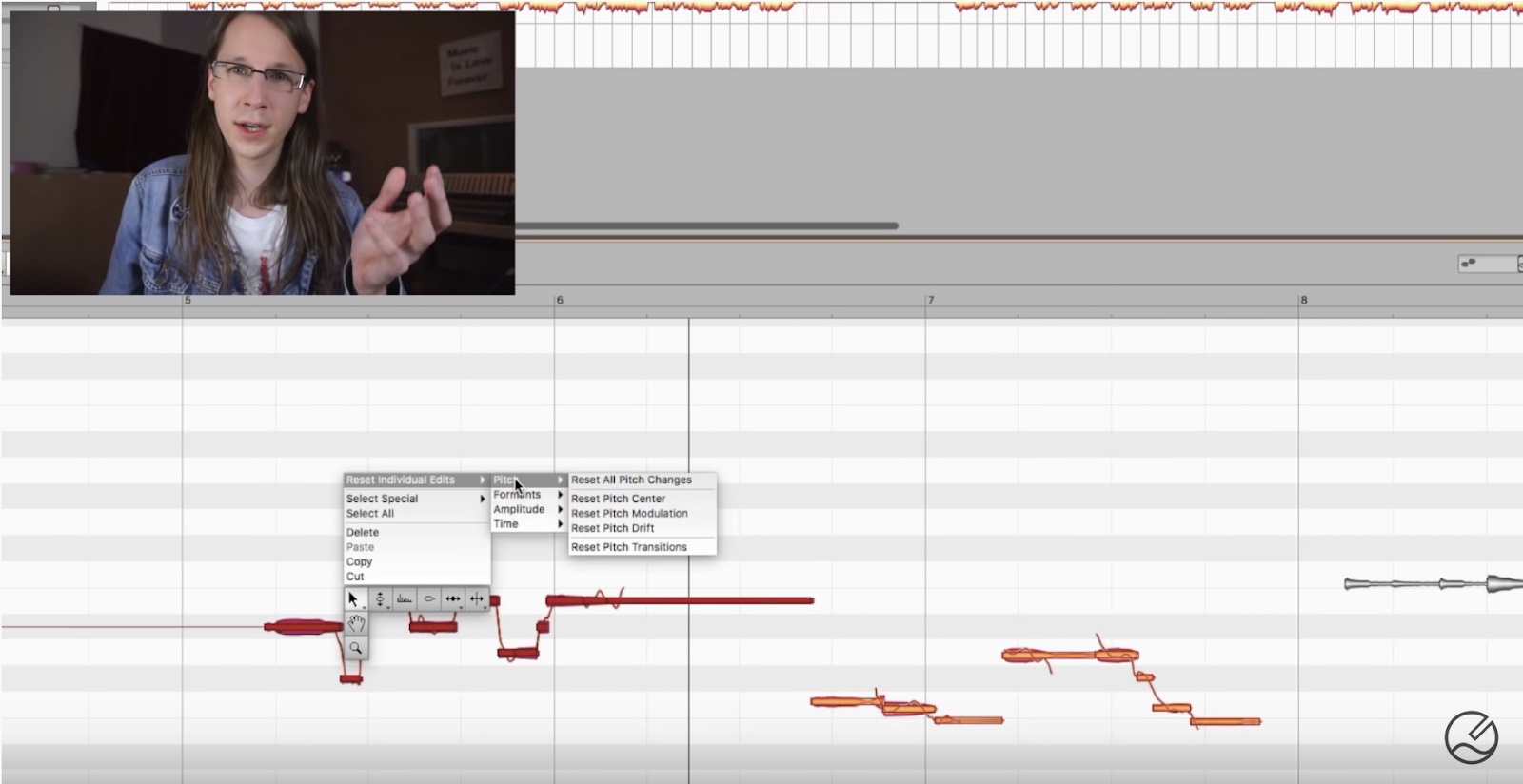

Screenshot from the YouTube tutorial video, “How to Use MELODYNE in a natural way?” by user White Sea Studio, posted September 24, 2018.

Over the last quarter century, digital pitch correction has become a ubiquitous practice in commercial and home studios. It is the practice of “tuning” voices and other instruments post-performance, a step in the music production chain on just about any recording intended for public release. Most people outside of the industry associate this practice with the software Auto-Tune, which gained notoriety and infamy (along with its status as household name) throughout the first two decades of the millennium for what music producers identified as its capacities for tuning voices without artifact and its extended uses as a vocal effect (à la T-Pain, Ke$ha, Kanye West). Melodyne, though used just as frequently as Auto-Tune, rarely comes up in popular discourse. Yet during the years that Auto-Tune was getting all the hype and taking all the flack, engineers quietly took up Melodyne as a “more musical” and “more natural” (hear: less conspicuous) way to pitch correct.

As I have written elsewhere, through the mid aughts, Auto-Tune became coded in the US popular imaginary as a “Black” sound because of the growing use of the Auto-Tune effect in hip hop and R&B. Equally, it was coded as a tool that allowed singers to “cheat,” though when the question came up, it was almost always about a female performer. When I began interviewing pop producers and engineers in 2014, however, I was presented with a picture of pitch correction with a different, “more human” tool at the center: interlocutors reported, “if someone’s actually tuning a vocal now … they’re using a program called Melodyne, which is way better,” and, “[Melodyne] is a little more human, a little more forgiving.” Similarly emphasized on the Celemony website are statements from producers like, “After using Melodyne it doesn’t feel like it’s a processed track. It feels like the original track—[has] just been taken to a good place.”

Screenshot from Justin Timberlake’s 2018 video, “Man of the Woods,” in which he gets back to nature.

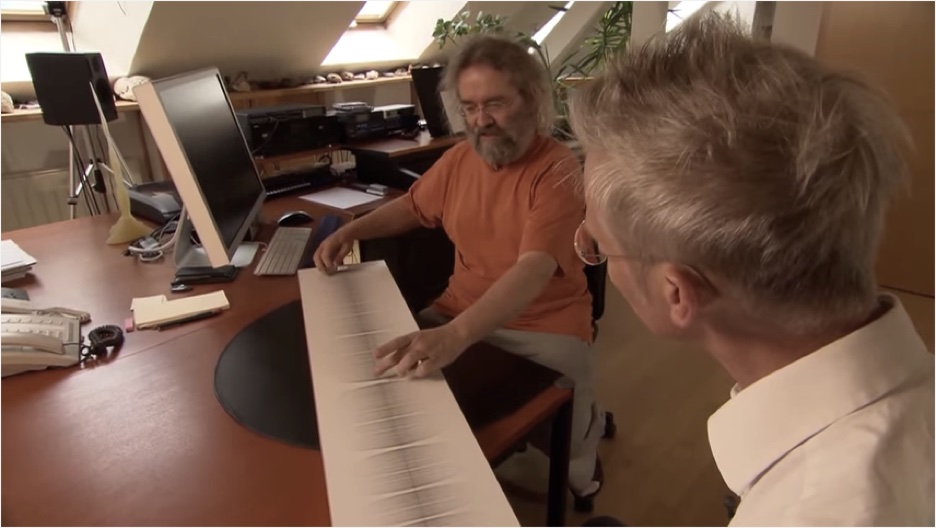

In 2016, I spent a day in Peter Neubäcker’s apartment office in Munich, Germany, interviewing him about Melodyne, which he invented. We were sitting and contemplating a 3D model of the sound he had used exclusively, and over the course of many years, to test the tool which would, as he imagined it, “free sound from its pitched and timed parameters,” making it so that a recording might be just the start of a composition, not the end. The software would enable users to move sounds around, stretch them out, rearrange them, all while preserving, if desired, the sounds’ timbral specificities. Using the sound of a single plucked guitar string (which we gazed upon in two-foot, 3D-printed plastic form), Neubäcker hoped to learn what sound was made of, to research its ‘true nature,” by asking questions like, “What does a stone sound like?”

Screenshot of the video “Melodyne inventor Peter Neubäcker (film portrait)” featuring Peter Neubäcker demonstrating a self-built Pythagorean monochord.

“I don’t know so much about that. To me it’s all rubbish,” he said when I asked him about his software as a pitch correction tool. He was not incredibly acquainted with pop music and other genres associated with pitch correction, he explained, because he does not like them, and because the use of his software as a vocal tuning mechanism is the use that is the least interesting to him. He did say, however, that it might be interesting to the extent that it freed singers from the strict relationship of pitch to expression, and might allow singers to “unlearn” this and explore other possibilities. Neubäcker’s interests present almost a perfect antipode to those of Auto-Tune inventor Andy Hildebrand, who sought to fill a gap in the music software market and fix a “problem” that technology had not yet fixed. Neubäcker, by contrast, wanted to recuperate the “reality” of pure sound by freeing it from the recording’s illusory truth.

I see a more-than-accidental connection between Neubäcker’s originary thinking as well as his narrative of sound-as-pure-object and the language used to describe Melodyne by its user community. Melodyne was lauded by users as a “natural”-sounding improvement upon Auto-Tune because it helped voices achieve or return to their somehow elusive “natural” state. That naturalness was concomitantly being threatened by Auto-Tune, whose “bad” reputation made it sit uneasily with the “purity” so often privileged when it comes to both voices and musical art. Melodyne became Auto-Tune’s natural alternative. As the product was pulled toward certain uses, the language of the marketing materials was updated to reflect these new desires. Whereas in the first four versions of Melodyne pitch correction was barely mentioned, on the Melodyne 5 web homepage, the first sentence now reads, “Thanks to the fundamentally improved ‘Melodic’ algorithm, Melodyne makes your vocal editing even better than before. With perfect, natural corrections at the press of a key.”

Software, like music, is so often taken for granted as immaterial, abstract, elusive, even fleeting. But users of audio softwares often bring heightened, almost enchanted awareness of each tool’s specificity, its sound, its functionality, its aural and cultural meaning. Additionally, at the center of Melodyne is an extremely material conception of sound, a conception that references not fads, but “ancient principles.” Melodyne evolved to animate the desires of a user community, and, in many ways, the interpellated fantasies of how racialized and gendered subjects sound. But the work is not meant to show. The software object dissolves into something “inaudible, sensitive, natural”—enacting the kind of disciplining that leads one to believe it was their idea in the first place, that they have simply returned to the form that was always there.