Musical Time Travel: Motivic Reuse in Avengers: Endgame

There is a lot to unpack in Avengers: Endgame, which serves as a means to tie a ribbon on more than a decade of Marvel films while hinting at what is in the future for the studio. Alan Silvestri, now scoring his fourth Marvel film (he also scored Captain America: The First Avenger, Avengers, and Avengers: Infinity War prior to Endgame), draws on a number of his prior scores – one benefit to long running franchises. Which motives recur and which material is left by the wayside in a three hour film meant to serve as a culmination for the six original Avengers, and how do those choices get made?

I’ll note that as with Back to the Future Part II, also scored by Silvestri, and actively acknowledged in Endgame as the inspiration for its core narrative conceit of time travel, this essay does not count portions of Avengers: Endgame where we hear the music from prior Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) films in the same context we originally heard it as a musical reuse, per se. Audiences need to hear the Avengers title theme during the shot of the camera panning around the original six-person team to confirm that the time-travel has, in fact, worked. In the case of both franchises, when we see earlier musical material alongside earlier visual material in the sequels, it’s not a reuse – it’s the same use we’ve already seen in the context of those previous films. One such moment in Endgame merits special mention even though time travel is involved: the reused music for the Soul Stone that plays on Vormir feels more earned here than in Infinity War. The feelings of love and friendship between Hawkeye and Black Widow are mutual, which makes the sorrowful piece of music feel more honest than it did with Thanos and Gamora in the previous film (Avengers: Infinity War).

Similarly, I am also not counting new motives written for Endgame that play multiple times. Tony’s funeral music plays twice, for example, first as Captain Marvel saves Tony in the first few minutes of the film, and again during his funeral in the film’s end. The New Avengers theme plays twice as well – once when Captain Marvel lands the spacecraft, and once as the New Avengers arrive through Doctor Strange and Wong’s portals in the final battle. This essay is focuses solely on musical material lifted from prior films in the MCU.

It’s tempting to take the easy way out here: the simplest answer to which motives recur from prior films is that Silvestri only reuses material from those films in the MCU he scored – the Captain America theme (by Silvestri) plays in full at least three times while neither Iron Man’s theme nor Thor’s theme (none of those films list Silvestri as composer) have any significant role to play in this film. However, this simple answer ignores something interesting with regard to how these films are credited: what does and doesn’t count as Silvestri’s work is more complicated than it might immediately appear.

The complication of Silvestri’s involvement with the other themes involves the chronology of the MCU itself. In the first Avengers film, Silvestri includes slightly altered versions of the main themes from Iron Man 3 and Thor: The Dark World, both of which had yet to be filmed, let alone scored – and by Brian Tyler, not Alan Silvestri. The Iron Man 3 theme plays during “Arrival” from 0:43 – 0:50 in the bass (before being subsumed by a rising motive I’ll return to a few paragraphs down the page), and the main theme from Thor: The Dark World plays during Thor’s landing on the Quinjet from 0:10 – 0:20 of “Don’t Take My Stuff.”

If we accept that Silvestri has some experience working with themes credited to Brian Tyler, the simple solution posited above that Silvestri reuses themes he composed for other MCU films falls apart. So, why don’t the motives for Iron Man and Thor reappear in Endgame? I argue that these themes – alongside the theme from Doctor Strange, which, as Grace Edgar mentions, appears for the briefest moment – have two problems that prevent them from making significant entrances in the soundtrack to Avengers: Endgame.

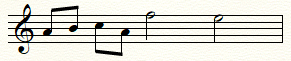

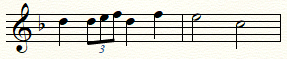

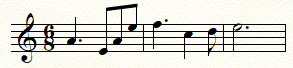

The first is a virally popular (and, in my opinion, overblown) criticism of the MCU’s music: these themes all sound quite similar to each other. In the context of the ensemble Avengers films, they are therefore not useful in assisting audiences with identification of individual characters on the screen. Compare for example Iron Man’s theme to the theme for Doctor Strange (Figures 1 and 2 below).

Note that the Iron Man theme and the Doctor Strange theme both start on tonic, run up the minor scale two notes, and return to tonic. They may diverge after that (in parts untranscribed), but in fragmented form, the two are difficult to distinguish. Similarly, the Iron Man theme and the Thor theme (Figure 3) are both in A minor, and both start on tonic, and proceed to the sixth scale degree of F before resolving to the dominant. With starting and ending points the same, it’s difficult to tell which character is being referenced. Keep in mind that character themes must be readily identifiable by an audience without significant musical training in order to function as such. This is, of course not a problem in the solo films, but the similarity of these themes do not facilitate audience identification in the context of the team-up Avengers films.

What, then, are general audiences trained to readily hear and understand with regard to character themes? I’ve argued previously that one musical topic audiences of superhero films understand is a topic of truth, justice, and the American way. Cap’s theme is more immediately distinct from that of Iron Man and Thor. Additionally, the similarities between Silvestri’s theme for Captain America to both Copland’s “Fanfare For the Common Man” and Williams’ famous theme for Superman, allow audiences to recognize recognize that this is the theme of an American hero. This theme does more than tell us when Steve Rogers appears on the screen, it tells us who Steve Rogers is – a representation of the “common man” idealized by Copland in the wake of the Second World War.

Iron Man and Thor’s themes do not have nearly as strong a connection to a musical topic as Captain America’s theme does with the topic of American patriotism – this is the second problem with those themes regarding their absence in Endgame. What musical topic identifies the characters of Iron Man or Thor? For Tony Stark / Iron Man, it might be the “bad boy” rock genre represented by AC/DC’s “Shoot to Thrill,” which serves as his entrance music in both Iron Man 2 and the first Avengers film. That said, after the events of the first Avengers film, Stark’s character shifts from a hotshot “genius, billionaire, playboy, philanthropist” to a victim of PTSD dealing with a variety of insecurity. Rebellious rock music might function well to identify Stark as the former, but not the latter – by comparison, Captain America’s character (and therefore the musical topic identifying it) does not change as significantly throughout the 22 films in the MCU.

As for a single musical topic to readily identify Thor to an audience, Thor as a character spends a significant portion of Endgame coming to terms with a new identity as a failed hero; hence, no one piece of music from his past (films) can represent him here. Additionally, Thor’s biggest emotional moment in the film—when he exclaims with no small surprise, “I’m still worthy”—has no music underscoring it, as it takes place during a transition to the opening sequence of Guardians of the Galaxy.

There’s one theme that, like Thanos himself, makes the jump through time from the revisited past back to the present of Endgame. The first Avengers movie (which, as noted above, is revisited during Endgame) is bookended with a four-note rising motive: E F# F# G. It first plays as a servant addresses Thanos, discussing the location of the Tesseract (it’s on Earth, after the events of Captain Marvel, where we last chronologically saw it). That same four-note figure then plays as Iron Man carries the nuclear bomb through the portal created by the Space Stone / Tesseract.

Right as Stark enters the portal, the camera cuts to a reaction of the S.H.I.E.L.D. agents celebrating that no nuclear explosion will happen in the skies above Manhattan. In Avengers: Endgame, during the final faceoff between Iron Man and Thanos (notably, at the moment Doctor Strange raises a single finger, signifying the “one way” the Avengers can claim victory), the rising figure begins to play again exactly as it appears in the first film. This time, the camera doesn’t cut to a different scene – and to whom does that motive direct the viewer? We were told in Infinity War: “Thanos…He sent Loki. The attack on New York. That’s him.” The silence following the E F# F# G cue is used to maximum emotional effect in Endgame – in both of the showings I’ve attended, the audience collectively held its breath as Thanos raised his hand, and then cheered, as if we were cast as S.H.I.E.L.D. agents observing from afar that Tony Stark had saved us one final time

Silvestri uses this bit of musical time travel to connect the climax of the first film to the climax of the fourth film brilliantly. In a similar vein, the Captain America theme – the one character theme he reuses multiple times – is itself fixed in time: that brassy, trumpet line so strongly invoking Copland belongs to the 1940s, as does Steve Rogers himself –Bradley Spiers notes the film closes by having him return to the 1940s he originally came from, dancing to a record we know he owned in Winter Soldier. Silvestri’s sparseness in reusing material marks each reiteration as vital to understanding the film not as one stand-alone entity, but as the culmination of a story told over the course of twenty-two motion pictures.