Not Like Us: AI and Aberrant Listening

In November 2024, Canadian rapper Drake filed to sue Universal Music Group and Spotify in the wake of an ongoing feud with American rapper Kendrick Lamar. This was unsurprising, given that Lamar’s diss track “Not Like Us” implicated Drake as, among other things, a sexual predator. The basis for this lawsuit was less expected: it accused these companies of unfairly securing Lamar’s rankings by using nonhuman (bot) listeners. This highlights issues broader than Drake’s success and personal integrity: the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) listeners and how streaming platforms, in an attempt to contend with them, illustrate assumptions about normative “human” listening. As Liz Pelly highlights in her January 2025 Harper’s Magazine piece, AI has already sparked controversy in other areas of music, such as production. Musicians—including Drake—have wrestled with the growing prevalence of artificial intelligence in matters of artist representation and revenue. Listeners, however, have generally found themselves to be passive auditors to these issues. Only more recently has the looming threat of AI extended from “Fake Art” to “Fake Audience.”

When I read about this lawsuit—and especially how Spotify defines and deals with “fake” listeners—I found myself reacting not to Drake’s loss but to this concern about listening agency. I thought of the many times I had been flagged as a bot by captcha and search engine programs because I was behaving in supposedly “abnormal” ways (e.g., navigating too quickly). How, I wondered, will AI-based streamers contribute to assumptions about “normative listening?” How does one identify—or even define—fake listening? Spotify’s primary metric tracks unnatural spikes in listener data: it implicates bots by looking for what the company defines as “unnatural” relistening. Ultimately, the material consequences fall to the artist, who may, at best, lose stream counts and royalties and, at worst, be fined or banned. Is Spotify’s metric fair? Is intense relistening truly aberrant or inhuman?

Looping, Listening, Liking

Claims about “normative” listening and repetition (and the boundary between non/human music) have been in question long before AI. Elizabeth Margulis and Luis Manuel-Garcia examine historical anxieties about musical repetition, which has often been interpreted as juvenile and banal. In contrast, as they illustrate, musical repetition—including relistening—can be powerful and pleasant to listeners. This evidence often manifests in music cognition research. In several recent studies, listeners were repeatedly exposed to identical musical excerpts in different conditions: some heard the repeated excerpts once per day, and others heard randomized repeated presentations in a lab. Szpuner et al’s 2004 study in particular illustrated that incidental listeners—those hearing the music in the background as one might listen to Spotify—showed a continuous increase in enjoyment even after hearing randomized excerpts up to sixty-four times in a single lab session. As David Huron explains, relistening can produce pleasure-reward responses originating from fulfilled anticipation. He even suggests that listeners may benefit from repeated exposures as they can afford a particularly focused mode of listening.

These studies do not attempt to quantify the limits of pleasurable relistening; notably, none of them deal with immediate replays—loops—either. To some degree this may result from the fact that these investigations trace their lineage to the 1960s and 70s, when the general listenership would have found looping to be considerably more effortful than it is today. Only recently—as digital technology has made repeating essentially automatic—has preliminary research even acknowledged intense relistening in everyday life and proposed it as a relevant, potential factor in music recommendation systems.

Despite this gap in the scientific literature, musicologists, media scholars, and critical theorists have suggested that such behavior is a hallmark of contemporary life and that replay technologies—including Spotify—actually perpetuate it. Robert Fink follows Jacques Attali in arguing that consumer culture necessitates musical repetitiveness (both in terms of repetitive music but also repetitive listening). Evidence outside of the lab strongly correlates with the observations of these scholars, too. YouTubers, for instance, upload ten-hour versions of repeating songs, so that listeners can seamlessly loop them. In my own forthcoming qualitative work on music and social media, interviewees often spoke of looping single songs for hours at a time. Spotify listeners have even pitched looping options to the platform, hoping for, in addition to the existing replay button, a feature that would allow the user to loop part of a song. They are not the first to suggest segmental looping either: musicians have sought out hacks and third-party apps to use section loops in their practice regimens.

Separate arguments might discuss the origin and value of intense relistening. One could consider these patterns, as Theodor Adorno might, a degeneration of deep listening. Or, one could, as Mack Hagood might, consider intense relistening as a protective, calming (“orphic” as he says) use of music technology to combat the contemporary malaise of “unprecedented choice” and the “need” to “hear what you want.” Has technology merely unmasked an innate musical instinct or has it synthesized it entirely? Regardless, evidence uniformly supports, at the very least, that there is nothing “inhuman” about repetitive listening: it is anticipated and commonplace.

Spotify’s Threshold for Aberrant Listening: Unclear

I would not expect Spotify to consult music cognition or critical theory in their policy development (although I would argue they should), but one would hope they are at least forthright about the ways in which they distinguish between “natural” and “unnatural” relistening. Spotify, however, is not transparent about its detection tools. The platform does specify its threshold for counting streams, which requires at least thirty seconds of play. But it does not offer any quantifiable limit for “good faith” looping. In fact, the company explicitly denounces “inorganic” fan looping, suggesting that these actions will be “captured” by their detection systems, without specifying how these formulas distinguish between in/organic looping.

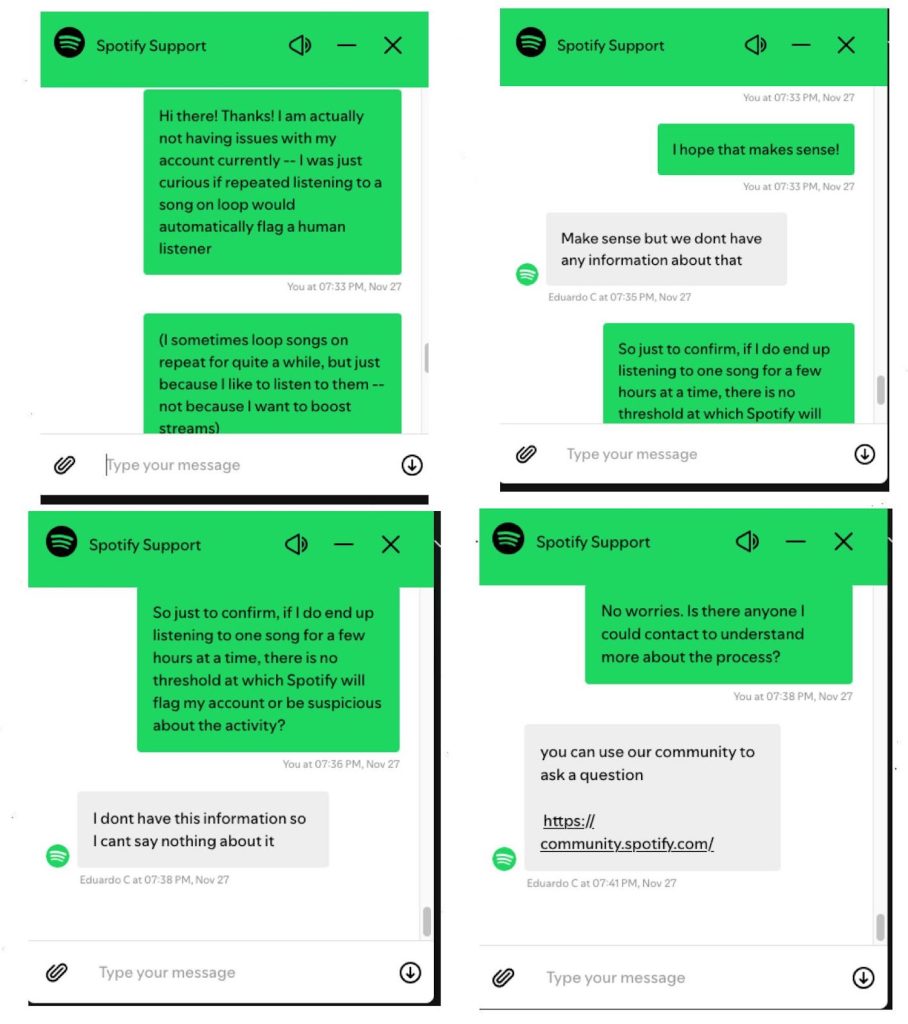

Admittedly, even the most obsessive looper cannot physically achieve the amount of bot streams that have prompted drastic federal action in cases such as the recent USA vs. Michael Smith. Notwithstanding these boundaries, listeners have expressed concerns that more than twenty loops from one IP address might be enough to flag an account; others posit that algorithms target certain listener-stream ratios. Even in Smith’s case, the defendant sought to override anticipated looping penalties by distributing his billions of bot streams across thousands of songs. Seeking clarity on this issue, I contacted a (human) Spotify support advisor to inquire. As shown below, I was simply told, “We don’t know.”

Labeling Loops as Inhuman Acts

Drake’s accusation highlights a critical concern with emergent technology. Human listeners are forced to contend with the fact that as streaming policies deal with the rise of nonhuman listeners, they are patrolling human behavior, penalizing the very looping their platforms enable. As a result, listeners are beginning to mold their behavior to satisfy platforms’ policies. This could become especially problematic for specific listener groups. If, for example, anecdotal associations between neurodivergence and looping are accurate, these policies would negatively affect such groups. Ultimately, streaming policy metrics may unfairly punish emerging and underprivileged artists as listeners are burdened with a moral conundrum: do they indulge in relistening to support their favorite artists or do they restrain their behavior in order to protect them?

Exploitative AI certainly poses numerous problems that require ongoing mitigation. However, humans already face a growing and often inequitable burden of proving they are “real.” Listeners and artists deserve an informed explanation as to how their behavior is being evaluated. Ideally, such assessments would consider research about listening and cautiously navigate its gaps. When streaming services flag listeners as, to borrow the words of Lamar’s diss track, “not like us,” one must consider how such policies play out in greater musical ecologies. AI streams expose our assumptions about what makes listening human, especially when those assumptions play against what humans actually do.