Quick Takes — The Sonic Makeover in Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age

By Kate Mancey

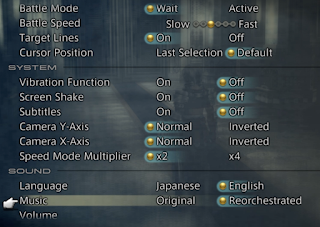

Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age is the latest HD remaster from Square Enix, and with it comes an extensive remastering of the original soundtrack. In contrast to previous Square Enix HD re-releases, such as Final Fantasy X/X-2 HD, this reorchestration uses much of the same musical material. However, when compared with the remastering in Final Fantasy X/X-2 HD, there is a vastly greater difference in sample and sound quality, changing the feel of the score without a need for drastic reorchestration. The HD release offers two main soundtrack options, the original PlayStation 2 music and a re-orchestrated version to accompany the now higher-fidelity graphics, with the ability to toggle between the two during gameplay (See fig 1). For those with a collector’s edition, there is a third ‘Original Soundtrack’ option available, this option uses the same tracks from the original soundtrack CD released alongside Final Fantasy XII in 2006 and is entirely recorded by a live orchestra, opposed to using synthesised instruments.

|

| Figure 1. Configuration screen from Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age. |

Although both the original PlayStation 2 and remastered versions are synthesised, each orchestration has a distinctive feel, perpetuated by the sound quality and timbres. To explore these differences in sound quality and timbre we can compare ‘The Dalmasca Easterland’ theme from each version, starting with the original music.

Whilst Hitoshi Sakimoto orchestrated the music for full orchestra, this piece still has a strongly synthesised feel due to both instrument sample quality and quantisation. The synthesised brass jumps out as the most un-natural timbre, as natural brass has a much larger spectral profile. The quality of the brass is better in the higher volume and higher pitched sections as there is some raspy quality to the sound which gives it a fuller, bigger feel, but it is a generally more subdued timbre than heard in live playing. The strings again sound heavily compressed and closer to a synthesised string-styled pad opposed to live strings. When the strings enter with the theme at 1’01’’ you can hear the strict quantising of the midi data which leads to a more robotic sounding melodic line as it’s missing humanised performance elements such as slightly extending and emphasising strong beats.

In isolation, the overall sound quality isn’t poor considering it was produced over a decade ago (2006), as sampling and synthesis technology has continued to develop over the years to create more sophisticated sounds. At its time of release, these synthesised orchestral timbres were cutting edge and as close to real instrument timbres as feasible in a video game, and were certainly a huge improvement on the timbral quality of previous Final Fantasy games. However, when compared with the HD remastering there is a stark difference in sound quality.

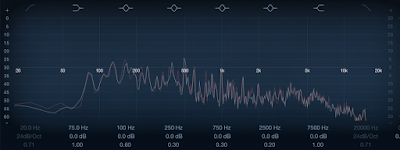

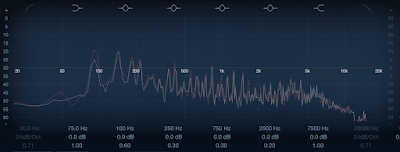

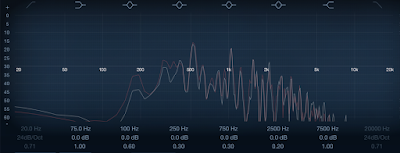

By adding humanised performance gestures and using much higher quality samples, the whole piece has a brighter and more open feel, the timbres have a richness to them and the individual lines are easier to distinguish. If we look purely at the overall sound output we can see that there is more varied frequency activity in the remastered track. The overall frequency pattern is the same, as the general orchestration is similar, but there is greater frequency response in the remastered version, especially in the upper regions, creating this more brighter, fuller sound (See fig 2.1 and 2.2). The slight change in instrumentation will also attribute to this, such as an increase in the use of strings and a lessening of brass in the remastered version. However, like the brass, the string samples in the remastered track are much better quality and greater attention has been paid to increasing the naturalness of the playing, making it more difficult to distinguish whether it has been synthesised or if it is a live recording.

|

| Figure 2.1 Frequency analysis from ‘The Dalmasca Easterlands’ at 0’26’’ from Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XII. |

|

| Figure 2.2 Frequency analysis from ‘The Dalmasca Easterlands’ at 0’26’’ from Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age. |

Although this isn’t Square Enix’s first HD remaster, it is the first remaster with such a distinct difference in audio quality. Final Fantasy X was more drastic in its reorchestration across the main musical themes, but if we compare ‘Tidus’ Theme’ from the original Final Fantasy X with its HD counterpart we see how relatively close they are in sound quality. The original track is very obviously synthesised, with the picked guitar accompaniment underpinning the main melody being both static in volume and in string attack, giving the music an obviously sequenced feel.

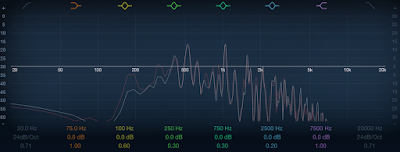

The synthesised instrument timbres in the HD version are marginally better than the original, but the overall sound is still heavily compressed and is missing the sparkle and musicality which The Zodiac Age remastering brings to life (See fig 3.1 and 3.2). The synthesised nature of the timbres is especially clear in the string pad and brass, with both missing some richness of timbre. Whilst the remastered track adds some vibrato to the strings it is a robotically flat vibrato across all notes, and a slower attack time without accounting for sufficient sound decay again adds to the un-natural feel of the timbres.

|

| Figure 3.1 Frequency analysis from ‘Tidus’ Theme’ at 3’15’’ from Square Enix’s Final Fantasy X. |

|

| Figure 3.2 Frequency analysis from ‘Tidus’ Theme’ at 3’15’’ from Square Enix’s Final Fantasy X HD. |

Jonathan Sterne suggests, ‘The promise of better fidelity has always been a Hegelian promise of synthesis and supersession’[1] and whilst the remastered tracks may be of higher fidelity, they don’t necessarily supersede the originals in terms of value to the player. In The Zodiac Age, the biggest difference in feel comes from the naturalness of the playing, using varying attacks and more natural decays, adding vibrato with greater musical thought. Whilst this creates more realistic stand alone pieces, the compression and quantisation of the original tracks could be advantageous to gameplay, facilitating better concentration as the music has fewer dips and peaks. The remastered tracks are arguably truer to Hitoshi Sakimoto’s compositions, as they allow the payer to hear these pieces on better quality orchestral timbres, but they lose some of the charm of the original tracks. In isolation, the remastered sound is significantly better. However, that doesn’t mean they are significantly better for the game, and it conjures up questions of authenticity.

In his discussion of re-orchestrations and authenticity, William Gibbons suggests it is easy to view these very “unreal” timbres as a problem to be fixed so fans can experience the music “how it was meant to be heard”,[2] and this has to be weighed up against the value of nostalgia for players who are familiar with the series and with the more electronic sounding timbres. It is also worth noting that whilst you can toggle between orchestrations you can only see the remastered graphics, which both adds to the nostalgic value of the PlayStation 2 music as it brings the old to the new, and adds significance to the remastered sound as it brings the scores to modern day fidelity expectations.

Regardless of the positive or negative impact of the remastered score on player enjoyment, there is an undeniably stark contrast between the sound quality of the original and remastered soundtracks, far greater than previous HD releases. A combination of better instrument samples and humanised playing, facilitated by an increase in the capabilities of music technology, has given the music of Final Fantasy XII a new lease of life.

Kate Mancey is currently completing her masters of research at the University of Liverpool. Her thesis focusses on the role of music and sound in virtual reality video games. She has presented papers on her research both in the UK and internationally, and has authored an article in the forthcoming volume of TransMissions. Outside of academia, Kate works as a composer and sound designer for video games and independent films.

[1] Sterne, J (2003). Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University Press. p.285

[2] Gibbons, W (2015). How It’s Meant to be Heard: Authenticity and Game Music. The Avid Listener. Available here.