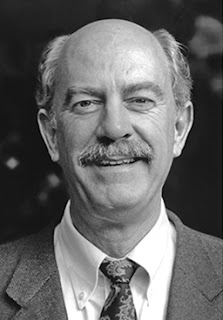

Remembering Alan Curtis

by Davitt Moroney

Alan’s death is a sad shock. For those who don’t know the details (which I received from Jennifer Curtis, his first wife—and daughter of the Charles Cushing, legendary professor in our own department), he died on his way into the hospital where he had an appointment to see his doctor. He had fallen and cracked the back of his head, and they’re still trying to sort out whether he had a heart attack, a stroke, or perhaps died because of loss of blood.

|

|

| Alan Curtis 1934-2015 |

I first knew him in 1975 when I arrived as a graduate student. He immediately took me under his wing, and I vividly remember a session when he demonstrated to me at the Skowroneck harpsichord in 116 Music what was so extraordinary about the Courante from Couperin’s second Ordre, with its unprecedented series of descending seventh chords. I also remember his glee at pointing out a magnificent unprepared—and unresolved—ninth chord in a C-major Louis Couperin prelude (“long before Debussy!”).

He had a reputation for arriving back in Berkeley in the second week of each quarter and leaving in the penultimate week. But in those days, long before emails and electronic attachments, he did whatever was necessary by mail, keeping in close touch with the students who worked with him. Every day, in the department office, the “Out” mailbox was filled with his correspondence, much of it addressed to festivals and record companies around the world. He worked very hard at his several separate careers.

I kept in close touch with him after I left Berkeley in 1980, meeting him whenever he was in Paris for a concert. After his retirement from the University of California, over the last 20 years, Christian and I have often spent two weeks in Venice in Alan and Piero’s apartment there. Apart from the direct view onto the Doge’s Palace in Piazza San Marco, there was an antique Italian organ, an antique Walther fortepiano, and an excellent modern harpsichord. We also visited them several times in their spectacular home just outside Florence. “It’s just 40 yards south of Florence,” Alan would say (referring to the official sign—FIRENZE—by the roadside), and we would have dinner at a local restaurant in a building where Galileo had lived. Their latest venture was the restoration of a beautiful historic building in Naples, some of whose walls are covered with frescoes by an important Neapolitan 18th-century painter. It’s very sad that Alan never had the chance fully to enjoy life in that newly finished home in Piero’s home town.

The Venetian apartment (bought largely with his fees from conducting at La Fenice) and the Florentine home (part of a 14th-century castello) were filled with beautiful paintings, antique furniture, and antique instruments.

When I taught summer courses in Venice for ten years, at the Cini Foundation (1989–99), Alan would always come up to Venice specially for my recital and take me out to dinner afterwards. He was warmly friendly and generous with career advice. His last email to me, just a couple of weeks ago, was helping with an issue with a recording company.

His book on Sweelinck remains an essential study of the composer. His edition of Monteverdi’s Poppea is likewise fundamental. But his best and most original research was actively published in concerts and recordings, not in articles and books. The research could be heard by those who knew what they were listening to. The set for Virgin of Monteverdi duets is breathtakingly beautiful.

Christian and I went a few years ago to the Spoleto Festival in Italy to hear his reconstruction of a Vivaldi opera, Ercole su’l Termodonte. Alan was delighted about the fact that one of the things that got this reconstruction so talked about was that the main singer who sang Hercules was entirely naked on stage (apart from a lion’s skin down his back) until the end of Act III, when his soldiers clothed him in royal robes. The singer had grown up in a Californian nudist colony and wasn’t the slightest bit bothered about singing coloratura da capo arias with no clothes on—he’d been singing in public naked since he was 15 and apparently he was the one who had proposed the idea!

But the scholarship behind the production was solid and important. The libretto survives but no score was known. It took Alan over 30 years to assemble most of the arias (I think he found 28 out of the 31) from eighteenth-century anthologies and arrangements, pieces he could identify from the libretto. He painstakingly put them in order, reconstructed the orchestration, and borrowed an appropriate overture from another work. The only thing missing was the recitatives, which had to be composed afresh (DVD HERE).

Alan was wonderful company, with endless gossipy (but never malicious) stories about other musicians. He was also a good cook—and Piero an even better cook—so evenings with them were always a highly civilized moment with someone who simply loved music, lived it and breathed it to the very end.

According to Jennifer Curtis, Alan and Piero were planning a trip in Asia ending up in Australia where Alan was to spend two months preparing an opera there.

He would have been 81 this fall.

Davitt Moroney, the noted Baroque keyboardist and music scholar, is Professor of Music at the University of California, Berkeley, and University Organist there.