“We Are Charlie Kirk” and the Gospel According to AI

The rapid fame of an AI-generated gospel tribute song titled “We Are Charlie Kirk” highlights strange new connections between American evangelicalism, political identity, and social media culture. Gospel here refers to both biblical-inflected language and a varied set of musical idioms that have circulated across Black and white communities of Christian faith since the late nineteenth century. While gospel is often racialized in current discourse as a Black genre—and African American sacred traditions remain foundational to its history—white evangelicals have long adopted, adapted, and politicized these styles. This was especially true in anthem-like ballads of the late twentieth century later folded into Contemporary Christian Music, which has become a soundtrack for conservative white evangelicals in the United States. It is within this contested political genealogy of gospel music that “We Are Charlie Kirk” operates.

Released on September 16—days after the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk in Orem, Utah—the track recently hit number one on Spotify’s “Viral 50 – Global” playlist and has accumulated over 1.8 million saves on the streaming platform. The song is attributed to a mysterious artist named Spalexma, who has released nearly 300 songs since December 2024, most with Christian themes. (Before that, Spalexma had only produced ten songs, all in Russian.) “We Are Charlie Kirk” fits perfectly within that recent catalog. The chorus centers Kirk using classic evangelical rhetoric:

We are Charlie Kirk, we carry the flame

We’ll fight for the gospel, we’ll honor his name

We are Charlie Kirk, his courage, our own

Together unbroken, we’ll make heaven known

Upon first listen, the song appears to be a straightforward tribute with sentimental lyrics and a swelling chorus modeled on 1980s white gospel power ballads like Steve Green’s “Find Us Faithful” or Vestal Goodman’s “Standing in the Presence of the King.” Scholars such as Douglas Harrison and James Goff have traced how this style emerged within white southern traditions and later became central to conservative evangelicalism. But the song’s emotional excess, uncanny vocal timbre, and viral circulation suggest a more complicated story.

Rather than only gaining popularity among conservative Americans mourning a political martyr, “We Are Charlie Kirk” also spread through ironic reels and remixes on TikTok. Soon after, it appeared on Instagram, X, and other social platforms. Despite being deemed “brain rot” and “AI slop,” the track inspired some creative engagement: musicians overlaid tracks, DJs provided remixes into genres like Brazilian funk, and meme accounts fitted it to an ever-expanding catalogue of surreal video clips. Still, the song’s earnest gospel idioms are disjunctive with the nihilistic memes it accompanies and have resulted in a kind of devotional parody—devotional not because it inspires piety but rather because its stylistic familiarity evokes decades of evangelical performance. The song’s simultaneous sincerity and artificiality reveal how evangelical nostalgia and digital political satire have increasingly come to draw on overlapping aesthetic features.

Gospel Music in Conservative America

The soundscape of modern gospel music is plural, including many historically rich subgenres like Black gospel, country gospel, and urban gospel to name a few. However, one strand of gospel performed by white evangelicals evolved over the twentieth century to represent conservative American values. Because the genre is so often racialized as a shorthand for Black sacred performance, this essay attends to the white evangelical strand that borrows from, overlaps with, and is frequently contrasted against Black gospel. For many Baby Boomers, gospel hymns such as “Just As I Am” are inseparable from the pervasive Billy Graham crusades of the mid-twentieth century that represented conservative cultural reform. In 1977, conservative activist Anita Bryant mobilized Christian song and patriotic hymns as part of her campaign to repeal a Dade County, Florida ordinance protecting gay and lesbian teachers. Belting “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and other gospel standards, she presented her campaign as both patriotic and religious, fusing evangelical music with her conservative political agenda. In the late 1990s, Christian songwriters like Bill Gaither popularized a loose definition of southern gospel using blended harmony, sentimental balladry, and certain nationalist themes that sold among conservative white evangelicals.

Even though church membership in the United States has declined over recent years and many evangelical congregations have adopted modern praise bands, gospel music remains a contested sonic medium through which certain evangelicals negotiate political identity. The genre has often followed mainstream musical trends, and some scholars consider it the historic foundation of a more diffuse genre called Contemporary Christian Music. CCM did not replace gospel so much as refine and commercialize a particular strand resonant with white evangelical audiences. Much of its success stems from conservative nostalgia: many songs evoke bygone days of televangelists and the imagined moral coherence of an earlier America. This explains why, in the wake of Kirk’s death, gospel music tribute videos proliferated almost immediately. Dozens of Christian songwriters also shared new songs memorializing him; one later expressed frustration that his heartfelt tribute was overshadowed by the ironic “We Are Charlie Kirk” AI parodies. The song has enabled Kirk’s viral outreach—one of his signature political tactics—to continue posthumously, though arguably not entirely in the way he intended.

Sacred Song or Meme Music?

A growing volume of AI-produced evangelical media demonstrates how easily religious affect can be simulated and circulated for political ends. Consider ViVO Tunes, a YouTube channel that emerged in November 2024 and has since become a prolific producer of what it calls “cinematic, high-quality AI-generated songs and videos that glorify God, Jesus, and the power of belief.” Recently, ViVO turned its content focus almost exclusively on Kirk, producing livestreamed “Christian AI Concerts” labeled “WE ARE CHARLIE KIRK” that recycled clips of Donald Trump, J.D. Vance, and Kirk himself. In one video, the channel used AI to make Vance sing “We Are Charlie Kirk.”

The video is an eerie amalgamation of evangelical religion and conservative politics that follows the lead of the Trump Administration to share similar AI-created propaganda. (Even a video featuring a Trumplike Messiah recently made rounds on the web.) Kirk-themed media has not been confined to the internet alone, though. At Prestonwood Baptist Church in Plano, Texas, megachurch pastor Jack Graham showed an AI-generated video of Kirk as a sermon illustration. Meanwhile, fake tribute songs by AI versions of Adele, Eminem, and Taylor Swift have amassed millions of YouTube views, illustrating “how quickly AI can fake emotion and fool audiences,” according to a recent article.

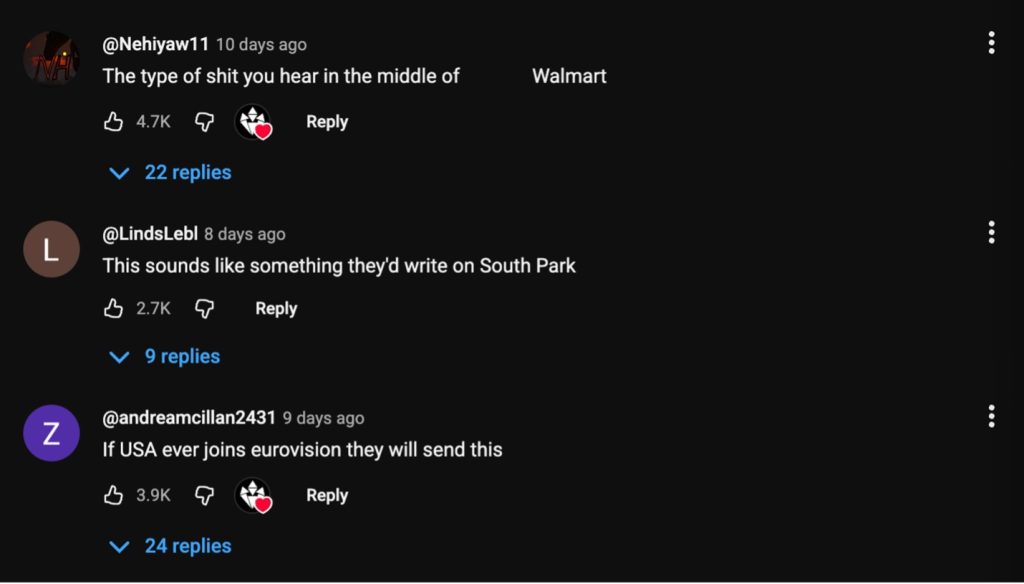

Evangelical culture has long been saturated by spectacle, and I’ve described elsewhere how Kirk’s memorial service in September channeled old evangelical theatrics of pious display. But “We Are Charlie Kirk” was not taken seriously by all listeners who shared it online; in fact, it has most recently circulated largely through dark humor and sardonic posts. The repurposing of gospel music for entertainment or ironic parody is hardly new. In the early twentieth century, a parody of the gospel standard “In the Sweet By and By” became an anthem among the Industrial Workers of the World, with lines like “Work and pray, live on hay / You’ll get pie in the sky when you die—that’s a lie!” Several folk singers reproduced the song in the midcentury, and it always roused laughter. What makes “We Are Charlie Kirk” different from earlier examples of gospel-laced humor is the speed and scale with which the internet enabled its transformation. Almost instantly the song became reusable audio that could be added to Instagram reels coupled with jokes about prominent Republican figures. And although many YouTube creators disabled comments from their videos to limit trolling, some viewers still compared “We Are Charlie Kirk” ironically to Walmart, South Park, and Eurovision. The internet does not enable parody alone but also collapses the distance between reverence and ridicule.

Screenshot of YouTube comments that frame “We Are Charlie Kirk” as ironic meme audio through comparisons to Walmart, South Park, and Eurovision, evidencing the collapse of reverence into ridicule in social media reception.

Considering Composition

The significant attention garnered by “We Are Charlie Kirk” prompts questions about how and why AI is used in music production. Songwriter Joe Linstrum offers his own perspective as a practitioner. Linstrum worked as a staff writer with my father on Nashville’s Music Row in the 1990s; now he composes commercial music for films, television, and advertising. While not involved with the Kirk song, he regularly integrates AI into his own creative process. Linstrum is a multi-instrumentalist and tracks all his own accompaniments, but “as a vocalist, I am very limited,” he conceded to me in an interview. “I have a hard time staying on pitch, and I don’t have much range.” His solution is to record his own vocal performance then upload the isolated vocal file to Audimee, an online AI vocal replacement tool, and select an AI voice to replace his own. He then downloads that vocal file, adds compression or a touch of reverb, and puts it back in the original song mix. The process is cost-effective for songwriters on a budget, since hiring “a real vocalist costs between 150-300 bucks a pop.”

Linstrum also elaborated on how AI aesthetics align with platform capitalism: “AI has boiled down the essence of what makes songs popular—just as Spotify has. If you have trained a model on all of the biggest tunes from the past 20 years, it’s going to spit out familiar, hit-sounding stuff.” He is skeptical that AI can produce anything avant-garde, but for listeners accustomed to the conventions of mainstream pop (or contemporary worship), AI outputs feel instantly recognizable. Its predictable chord patterns and verse-chorus structures help explain the viral traction of “We Are Charlie Kirk.” Because the song sounds similar enough to gospel music or even CCM, AI functions within it less like a ghostwriter—long common in the evangelical music industry—and instead as a system of producing recognizable affect without a stable author. Such anonymity lowers standards of use, so the track can be remixed and reposted without a sense of real ownership. It also shows how thoroughly the idioms of gospel have been reduced to transferable styles that circulate without the usual social intentions that once ground evangelical music.

AI and Affective Politics

The recent wave of AI-generated evangelical music reveals how easily political feeling can be manufactured and circulated without the human experiences that once grounded it. This new media environment echoes—with surprising fidelity—Donald Trump’s political mantra, a cacophony of internal noise shaped by what Lauren Berlant called the “Trump Emotion Machine.” AI music nonetheless complicates the relationship between politics and parody. The success of “We Are Charlie Kirk” reflects how online publics increasingly consume political affect as entertainment. Even (perhaps especially) those hostile to Kirk find pleasure in the song’s excess. Its parody functions as a critique of both evangelical conservatism and its musical tropes—the earnest fervor, heroic self-sacrifice, and emotional glosses of certainty. Yet its popularity also suggests that devotional songs and entertaining parodies draw on a shared musical grammar. The distance between these competing meanings is only another algorithm away. AI renders gospel music infinitely reproducible and always available for politicization—from sincerity to satire.

Gospel music was already highly reproducible and deeply politicized through megachurches, media ministries, and influencer culture. AI intensifies this condition by stripping away authorship and intention altogether. Algorithmic publics cohere around this shared audio even when listeners attach different—no, incompatible—meanings to the song. In this case, the distinction between sincerity and satire has nearly disintegrated, instead registering a more important priority for platforms: attention by whatever means necessary. If the twentieth century’s evangelical soundscape helped forge moral majorities, the twenty-first century’s AI-generated evangelical worship music may produce something else entirely: communities built not on shared belief but shared algorithms, bound together by the ghosts of familiar sounds. The gospel according to AI thrives on reproducibility and affective ambiguity. It’s less a moral imperative than another emotion machine, and for American politics that might be its most consequential feature.