Errantry in Three Folds

Reflections on the Errant Voices Conference, April 2022

Consider the adjective “errant.” The word might describe a misbehaving child careening through the galleries of the Uffizi in Florence, Italy, or a knight cresting the peak of a mountain in search of his dragon. An errant traveler might be pursuing a high-minded purpose or wandering aimlessly. They might be naughty or noble, resolute or dreamy, discreet or disruptive. As initially theorized by the Martinican writer and theorist Édouard Glissant in his 1990 book, Poetics of Relation, errantry is rhizomatic, a biological term that refers to the root systems of plants that are enmeshed, open, and migratory. Errantry is thus decentralized—non-monolithic and relational, rooted, but also nomadic and mobile. What does this definition implicate in the literal sense? There is no straightforward consensus.

Shortly before the COVID-19 lockdown, musicologists Martha Feldman and Bonnie Gordon joined with cinema and media scholar Kara Keeling to collaborate on a project that would explore errant voices in relation to performance, especially with respect to historical formulations of race and gender. The goal was to investigate errantry as a transhistorical, interdisciplinary concept that might bring seemingly unrelated musical sites into dialogue. In spring 2020, Feldman taught an interdisciplinary seminar at the University of Chicago entitled “Errant Voices” to explore some of these ideas. With additional support from media and music scholar Amy Skjerseth, an in-person conference at last took place in Chicago in April 2022 under the rubric of “Errant Voices: Performances beyond Measure.”

As a historical musicologist tasked with being the official notetaker at the Errant Voices conference, I was most taken by the moments of conceptual dissonance that surrounded the term. As I dutifully recorded the events of the weekend, it became clear to me that errantry and its lexical variants tangled as the terms conceptually expanded.

And yet, certain pertinent themes echoed throughout the conference in response to the open invitation extended by the term: neglected histories, the aftershocks of colonial violence, unconventional temporalities, the excluded (Black) femme, and the power of recuperative fantasy. Over the course of a long weekend, these themes provided quilting points for papers that spanned space and time, ranging from the curtained halls of the Ottoman court to the bayou of the American South, from the hazy annals of the sixteenth century to the technicolor drag shows of the present day. Errantry’s lack of clear boundaries produced papers about historical castrates, Italian castrati, Black blues and folk singers, trans singers, and Asian and Latina/o performers and their soundscapes, wrinkling the linear fabric of history and creating meaningful pockets and folds. In this reflection, I elucidate the way that these diverse musics shared conceptual resonance by exploring three errant folds: paralinguistic invitations, silence and surveillance, and the self-constructed nature of sound.

FIRST FOLD: Am I Invited?

The errantry of the scream was a recurring thread throughout the conference, inspired by Fred Moten’s theoretical work on exile and fugitivity, especially his 2003 and 2013 books, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition and (with Stefano Harney) The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study but also his recent trilogy bearing the supertitle consent not to be a single being (2017–2018). Papers also explored the nature and function of other non-linguistic sounds, including yells, high notes, and technological manipulations. In their departure from the confines of language, these sounds contain the potential to express intergenerational pain and affective excess, or celebrate liberation from the confines of transparent signification. But what would it mean to interpret screams and adjacent sounds as specific invitations or deterrents?

In his paper on Yoko Ono’s 1981 album, Season of Glass, Joshua Takano Chambers-Letson positioned the scream as a tool that ultimately helped Ono express and work through, but not artificially overcome, her immense grief over John Lennon’s death. In Chambers-Letson’s hands, Ono’s scream functioned as an invitation, an entry-point into the emotional core of the music. Not all conference attendees interpreted her sound the same way. Others found it grating, off-putting, or simply intolerable, leading us to acknowledge that a sound that invites one person into a space might alienate another. Later presenters returned to considering the politics of invitation, to the sensation some have of being called or “invited” in by sonic experiences even as others feel repelled or disinvited.

The politics of selective invitation informed my reading of Freya Jarman’s paper, which dealt with operatic high notes that stretch and extend beyond language. Jarman made reference to a range of roles and examples: The Queen of the Night from Die Zauberflöte, Kaspar from Der Freischütz, Salome from Salome, King George III from Hamilton, Lucia from Lucia di Lammermoor, Kate Bush in her song “Babooshka,” and (in general) the band Judas Priest. Those for whom the call resonates might be seduced into the complex culture of diva worship. Others for whom a sound is too intense might be induced to reject a genre entirely.

Jarman argued that high notes tend to be emotionally charged, gendered female (regardless of their source), and associated with a collapse of reason. Within a large body of opera scholarship, moments in mad scenes have often been interpreted as liberatory; Jarman, by contrast, proposed that such moments only function within and against vectors of power that already position the individual as a combination of their gender, race, age, height, weight, and so on. Her analysis raises the question of whether high notes, as voiced by a given individual standing at the nexus of these vectors, extend a troubled invitation in much the way Ono’s screams do.

The notion of invitation also proved to be an important aspect of Deborah Vargas’s keynote about the transcendent power of “el grito” to penetrate the porous border separating the United States and Mexico. Vargas describes the Spanish term “el grito,” or “the yell,” as a unique expression of “Mexicanidad”/“Mexican-ness,” characterized by a low-pitched guttural sound that expands in pitch and volume over time. “El grito” is imprecise in form and pierced by whistles, grunts, and other interjected noises. While non-Mexicans might hear “el grito” as disruptive or impolite, Vargas showed that the sound is also protective, feeding into rich cultural codes that unite and empower a disenfranchised Mexican minority in the United States. The sound of “el grito” is thus one of excess, migration, and cultural continuity. It functions as a meaningful commonality within the sonic worlds of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. But “el grito” doesn’t issue an invitation to everyone. Most sounds don’t.

SECOND FOLD: Silence and Surveillance

The second fold extends from the first, a consequence of invitations issued and not issued, of unchecked desire and obligatory self-protection. Silence is a sticky term, comfortably theorized as both a form of suppression–via the intentional exclusion of certain voices from conventional histories–and as a means of concealment, a voluntary tactic employed by errant individuals to avoid surveillance. Silence is thus a tool both of the oppressor and of the fugitive. In this fold, I examine the relationship between silence and surveillance as a relation that emerges from the way errant subjects navigate dangerous spaces.

In his paper, Mark Burford recounted the unsettling story of the white spiritual singer Katherine Dickenson Tucker crouching in the bushes to overhear “authentic” Black folk songs that she later exploited in her successful career. The figure of the unwelcome outsider (the uninvited) lying in wait to profit off the ingenuity or novelty of the errant subject recurred in papers that spanned genre, time, and space. This form of theft belies a fetishistic interest in the errant other, even as errant figures are often excluded from conventional discourses and histories. In this case, could silence perform a role complementary to that of the scream, countering excess with nothingness? Could an errant subject choose silence over sound? Burford argued that Black academics contemporaneous with his white subject safely skirted around assessing the conservation efforts of white Spiritual singers, deploying a strategy of tactful silence while Tucker and other singers like her enjoyed successful careers on the backs of traditions that were not their own.

Burford wasn’t the only scholar reconstructing histories of silence at the conference. Katherine Crawford’s paper on Black castrates in the seventeenth-century Ottoman court argued that the silence and secrecy of these figures functioned as a protective measure against curious outsiders. Scholars today are still grappling with the wall of multigenerational silence that concealed the inner workings of the court throughout its long history. Crawford recounted a culture of silence both outside and inside the harem, an insulated space from which workers might be ejected due to the natural acoustics of their speaking voices. Discretion was both a practical requirement of the harem and a tool to protect the intricacies of court life from prying eyes—although silence did not prevent the damaging caricatures of Turkish castrates and other “exotic” people in popular Western music of the period. The protective culture of silence in the Ottoman Court resulted in grossly inaccurate accounts by visitors trying to decode its complex social order. Crawford also pointed to moralistic posturing by Western Europeans, who condemned castration in the Ottoman court while condoning it in the service of creating castrati at home. In sum, silence here was weaponized to protect an insular organization from the eyes and ears of outsiders.

THIRD FOLD: Making It Up

The third fold nests inside the first two, synthesizing these divergent approaches to sound and silence so as to query the very nature of errant self-construction. Is errantry dis-membering or re-membering? Dissolving or constructing? Among the numerous metaphors that circulated over the course of the weekend, I was most drawn to the metaphor of “make up” and the concept that one could “make oneself up.” To “make up” might mean to comprise, beautify, create, or, finally, to play pretend or make believe, introducing an element of fantasy and self-fashioning both inherent to and fundamental within the errant subject. Errantry might also be understood as taking charge of one’s own constitution in the biological sense, rejecting accepted molds and models of gender or race, realigning oneself vis-à-vis standards of stability and fixity, or rethinking and resituating oneself in relation to traditional family structures. This is what it means to “do one’s own makeup,” to participate in the endless unfurling of errant subjecthood and ways of being.

Grace Lavery helpfully unpacked “clockiness,” a term used by many trans people to describe the markers that expose the trans body (and every body) as relational, markers that sometimes undermine one’s ability to pass. In her paper on V/VM records, Lavery argued that the 1990s label’s records display what she called auditory clockiness, distortions that result in “music that fails to pass as music.” In this instance, sound manipulation created entirely new sound objects with a complex connection to their original sources, much as trans individuals form their own identities and ways of being in relation to socially constructed models of gender.

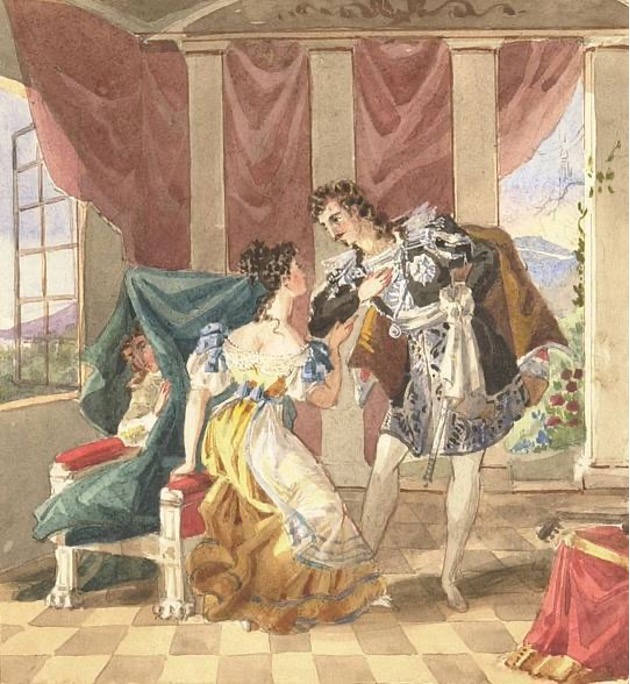

Anonymous watercolor, 19th century: Scene from Act II of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Marriage of Figaro, Cherubino hiding.

Martha Feldman’s account, which dealt with the ways trans singers navigate the world of classical singing, also showed trans performers remaking pre-existing sources, in her case trans singers making themselves up against the conventional backdrop of opera. Opera singers play roles that suit their voices. For trans singers, these roles might align with or contradict their offstage gender presentations and desires, thus creating new readings of old sources. Consider an untransitioned trans man learning the role of Cherubino as a mezzo-soprano, a situation that Holden Madagame described on his now-defunct blog and in interviews. As Cherubino, Madagame performed in the gender presentation that aligned with his growing inner desire, rather than with any outward appearance or identity. And in the process, he remade Cherubino. Using Lavery’s construction, for a singer on the cusp of transition, gone was the humorous homoeroticism of the pants role, of the woman dressed as a man revealed to be a woman by a change of clothes in Act II. Instead, during Cherubino’s disrobing and playful reprogramming, the man dressed as a woman dressed as a man is revealed to be a man after all. Now a fully transitioned tenor, Madagame sings roles that match his gender presentation.

An understanding of make-up and making up also informed Amy Skjerseth’s account of gender-fluid drag queen Sasha Velour’s “Alexandra” act. Velour uses silence to temporarily manipulate the seemingly restrictive generic boundaries of the lip sync act, interrupting the music with pantomime and public reflection. However, unlike the mobilization of silence and withholding explored in the silent fold above, Velour’s is a story of revelation, a build-up to the lifting of the curtain. As the lip sync act reaches its emotional peak, the performer strips down to a glittering, skin-tight bodysuit. Skjerseth argues that Velour replaces shame with transcendence. By lifting the curtain, Velour reveals entrenched instabilities between sound and source, authorship and performance, presentation and identification.

Why describe these isolated performances as errant? Theorizing errantry aims to generate richer understandings of the various folds and instabilities I have broached in this brief reflection on the conference discussion. Even the stakes of deciphering such a complex concept are high, to say nothing of the practices themselves. Errantry is alterity. Errantry is fecundity. Errantry lays bare relations of power. Therefore, while errantry proved to be an elusive concept over the course of the Errant Voices conference, it also proved to be a grounding and productive one. The three folds I describe here are offered only by way of a beginning.