Race and the American Musicological Society: Founding the Committee on Cultural Diversity

This essay began as part of a panel sponsored by the Committee on Cultural Diversity at the American Musicological Society’s 2019 conference in Boston, which marked the committee’s thirtieth anniversary. Chaired by Michael Figueroa (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), the panel also included Johann Buis (Wheaton College), Imani Mosley (University of Florida), and Charles Carson (University of Texas at Austin).

The uprisings against systemic racism of 2020–21 have forced many American academic organizations to grapple with their racial histories as they work toward more inclusive futures. I write as founding co-chair of the Committee on Cultural Diversity (CCD) of the American Musicological Society (AMS), which emerged in the early 1990s, and my goal is to document a history of equity activism in an academic field that has changed remarkably in the last several decades yet remains predominantly white. Establishment of the CCD is the focus here, not the committee’s overall history. I worked together with Patrick Macey (Eastman School of Music), the CCD’s first co-chair, and Lucius R. Wyatt (Prairie View A&M University), its second co-chair. This account relies on documents saved, reports in the AMS Newsletter, excerpts of minutes from the AMS board and council (provided by the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections), and memories.

Since its inception in 1934, the AMS has primarily brought together scholars who study canonical European musical traditions. For many of those who formed the Committee on Cultural Diversity nearly 60 years later, that hegemonic whiteness felt repressive. The CCD emerged from a grassroots campaign at a moment when peer organizations—such as the American Historical Association, Organization of American Historians, and College Music Society—already sponsored committees focused on racial justice.

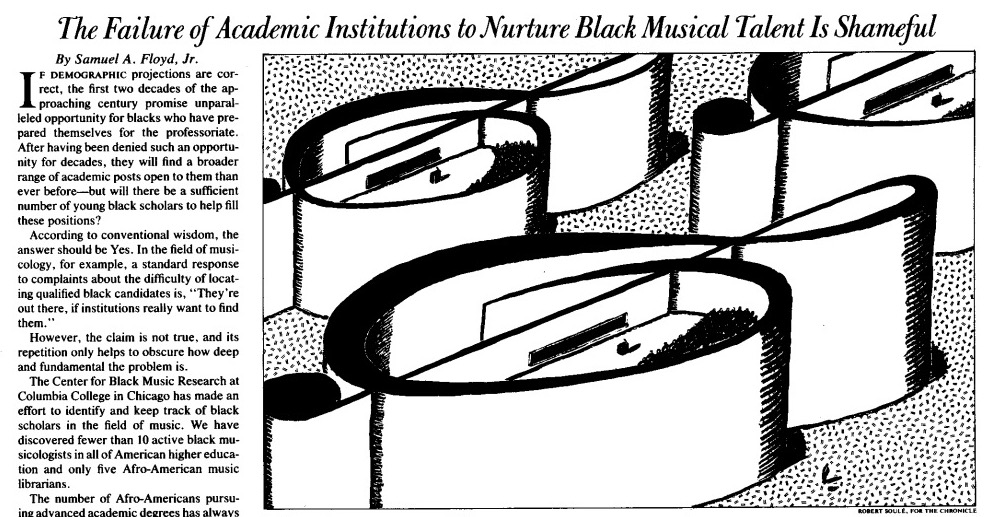

A key motivation for the CCD came from Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., director of the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago (CBMR). In 1990, Floyd published a call-to-arms in the Chronicle of Higher Education, laying out racial realities about the field of music scholarship. Floyd reported that only ten Black music scholars and five Black music librarians had been identified across the U.S. He wrote of the urgent need for Black academics to be “identified, nurtured, and recruited.” He used the word “hostility” repeatedly, lamenting “notions about the superiority of European music, ignorance of the black-music tradition and its relation to the European tradition, and a desire to protect curriculum time for existing courses and pursuits.” Floyd’s article inspired the formation of an interracial Committee on Minorities within the AMS Council. Soon, the name changed to Committee on Cultural Diversity, the first of many attempts to shape inclusive language.

Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., Chronicle of Higher Education, May 9, 1990.

The CCD’s first initiative was an open forum on race at the 1991 AMS conference in Chicago. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. shared the podium with the Renaissance-music scholar Howard Mayer Brown from the University of Chicago. The two men knew one another, in part because Brown participated in colloquia at CBMR. A standing-room-only crowd turned up, responding to rumors that Floyd and Brown would debate whether Black music was worthy of academic study. Those rumors, in turn, exposed problematic racial attitudes at the time among some AMS members. No such confrontation occurred, and the discussion was mutually respectful, exploring ways to foster a more diverse membership and welcome research beyond white European traditions.

In February 1992, the council version of the CCD petitioned to become an independent standing committee, requesting a structural change to embed racial inclusion within AMS’s governance. Citing a procedural detail, the board refused, sending the CCD back to the council for approval (the council is subordinate to the board, and it recommends ideas for the board to consider). Minutes from that board meeting report the negative vote matter-of-factly. My memory, however, registered the decision as enforcing the status quo by invoking a technicality. The CCD re-petitioned the board successfully in November 1992, becoming a standing committee. This request for a higher committee status might seem like a tedious bureaucratic detail. Yet standing committees could claim a slot on the annual-conference program, providing a way to avoid the AMS program committee and its routine rejection of topics outside of accepted white European norms.

The CCD’s initial membership included African American scholars (Rae Linda Brown, Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., Doris McGinty, Josephine Wright, and Lucius R. Wyatt) and white colleagues (Judith Lochhead, Patrick Macey, Mark Tucker, and me). Wyatt succeeded Macey as co-chair. In a 1992 letter, Wayne Shirley conveyed the resistance faced by scholars studying Black music, proposing a strategy to deal with entrenched program committees: “I suggest that we try to end-run the setting up of a special session on Cultural Diversity/Afro-American Concert Music/whatever, and concentrate instead on the musicological equivalent of Getting Out the Vote. . . . The more papers on culturally diverse topics (damn this locution! But I don’t know a better one) they see, the more seriously they will take all this.”

Reading issues of the AMS Newsletter from the CCD’s early years reveals the exclusions confronted by the committee. Women, people of color, and other minoritized members were mostly absent from the organization’s power structure, including both its elected leaders and awardees of prizes and fellowships. Photographs alone tell the story. The newsletter also documents change: in 1991, for example, African American scholar Eileen Southern became an Honorary Member.

In a video conversation, Lucius R. Wyatt shared his impressions of the racial climate in the AMS during the 1980s and early 1990s:

Lucius R. Wyatt interview with Carol Oja via Zoom, October 2019.

In its early years, the CCD launched several initiatives, all of which continue:

- Establishment of an “Alliance for Minority Participation in Musicology,” conceived to encourage existing Ph.D. programs to fund graduate students of color. This strategy worked around the fact that the CCD had no money for fellowships.

- Initiation of the “Minority Undergraduate Travel Fund,” designed to encourage undergraduates of color to attend annual AMS meetings. Fairly soon, it was renamed in honor of Eileen Southern.

- Founding of the Howard Mayer Brown Fellowship, which did not emerge directly from the CCD but rather was established by a group of Brown’s colleagues after his death in 1993. The AMS newsletter reported that the fellowship “seeks to increase the presence of minority scholars and teachers in musicology.”

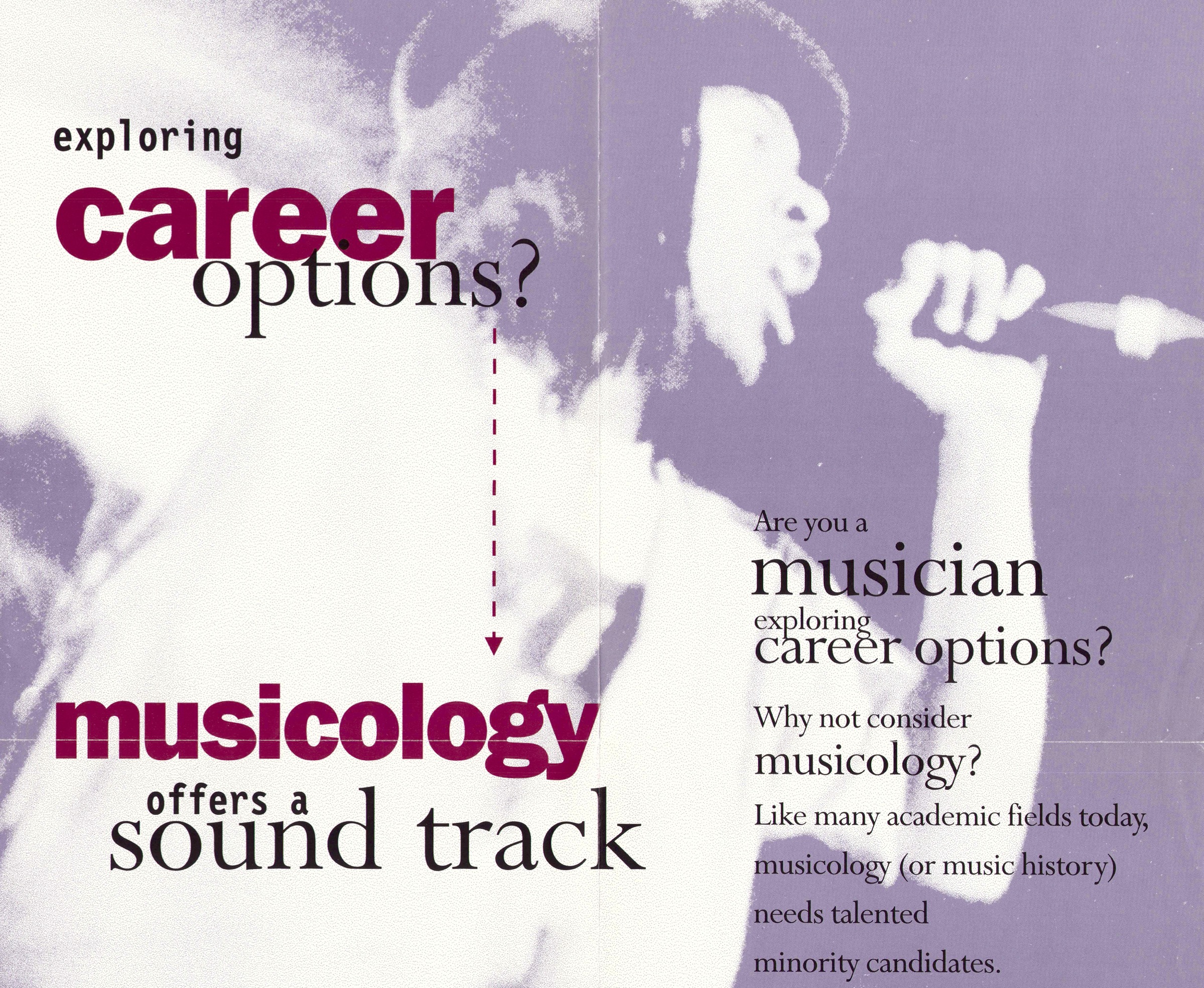

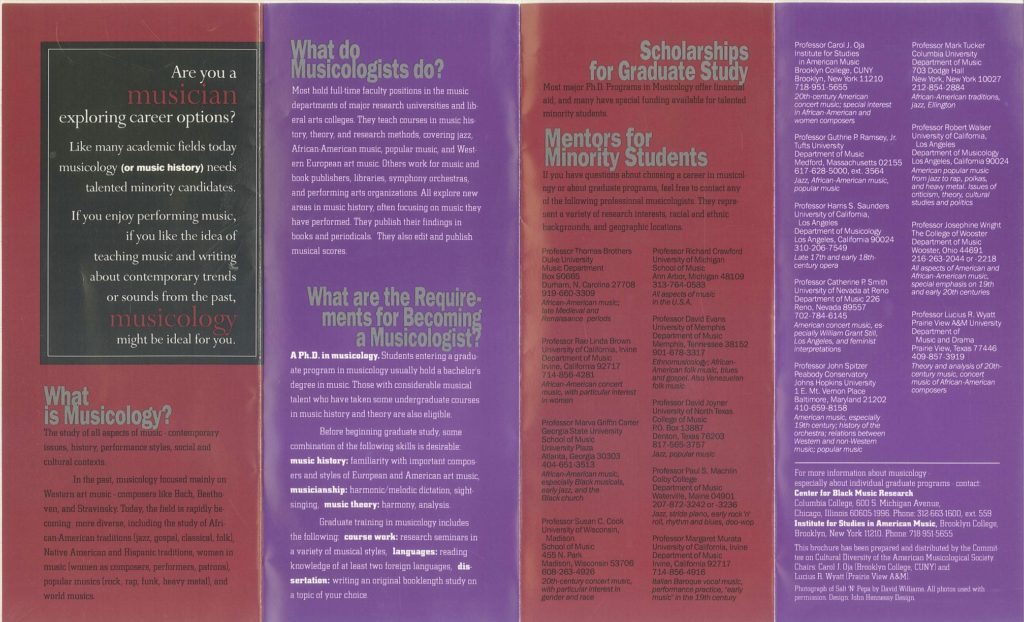

The CCD’s initiatives took off in 1995 at the AMS conference in New York City. The AMS invited the CBMR for a joint meeting, and activist-members functioned like community organizers, inviting participants to the conference who otherwise might have felt excluded or silenced. In anticipation, the CCD published a poster and brochure, which were snail-mailed to music departments at historically Black colleges and universities.

Cover and inside of an AMS brochure distributed to historically Black colleges and universities in 1995.

The CCD designed the brochure and poster to reach potential graduate students of color. From today’s perspective, the documents reflect their moment in time. The multiracial images of musicians across the pamphlet, for example, were chosen to signal a hopeful vision of music scholarship, suggesting that the topics studied could embrace musicians of color and reach beyond highbrow traditions. Those messages were largely aspirational, countering the era’s restrictive attitudes. Lucius R. Wyatt reflected on the labor at the core of recruitment and the poster’s distribution:

Lucius Wyatt interview 2019.

Over the ensuing decades, many in AMS have built on the foundation established by CCD, working diligently to confront racial inequities, especially through mentoring multiple generations of graduate students of color. Notable developments have included the Judy Tsou Critical Race Studies Award and the Robert M. Stevenson Award in Iberian and Latin American Music. A committee on Race and Ethnicity formed in 2017, which has recently been renamed the Committee on Race, Indigeneity, and Ethnicity. All these initiatives required broad-based community support and vigorous implementation. Yet with its deep history of racial exclusion, the AMS has an urgent obligation to reinvigorate antiracist initiatives on a regular basis. The stakes of the current racial reckoning in the U.S. are high, and by confronting their troubled histories, academic organizations like the AMS have an opportunity to play a productive role in shaping a more equitable environment for research and teaching.