Sounding the Path to Dignity: Chile after October 2019

This essay is a contribution to the Musicology Now Roundtable, “Protest in Latin America: 2019 and Beyond.”

“Si el río suena es porque agua lleva” (“If the river sounds, it is because it carries water”) is an old Spanish proverb broadly used in the Hispanic world. It metaphorically expresses that a fact can be inferred from any sign. When interpreted more literally, the saying acknowledges sound as the unequivocal index of something else. Therefore, it is hearing—not seeing or touching, as traditional ontologies have most typically sustained—that provides valid and sufficient sensorial evidence that something exists.

The ongoing social uprising in Chile began with an act of civil disobedience. A massive subway fare evasion to contest a price hike put in place on early October 2019, which had enraged wide sectors of Chilean society who were exhausted by decades of neoliberal policies and abhorrent inequality. Protests grew over the following days, reaching a climax on the night of October 18. There were violent demonstrations and the thunderous noise of a massive cacerolazo: from balconies and windows across the country, people banged pots and pans for hours on end in resonant defiance to the government’s repressive response to the demonstrations. The roaring continued for days, sounding an unequivocal sign that something big was happening once and for all. In the five intense months that followed, people protested by marching, singing, dancing, playing instruments, and banging pots. On the front line, protesters resisted the police’s tear gas bombs and rubber bullets with rocks and bonfires, as well as with music, singing and dancing. Ever since, Chile’s demonstrators have mobilized “Dignity” as a principle and motto that asserts their right for a better life by annihilating the pernicious legacies of Augusto Pinochet’s regime, including the Constitution of 1980.

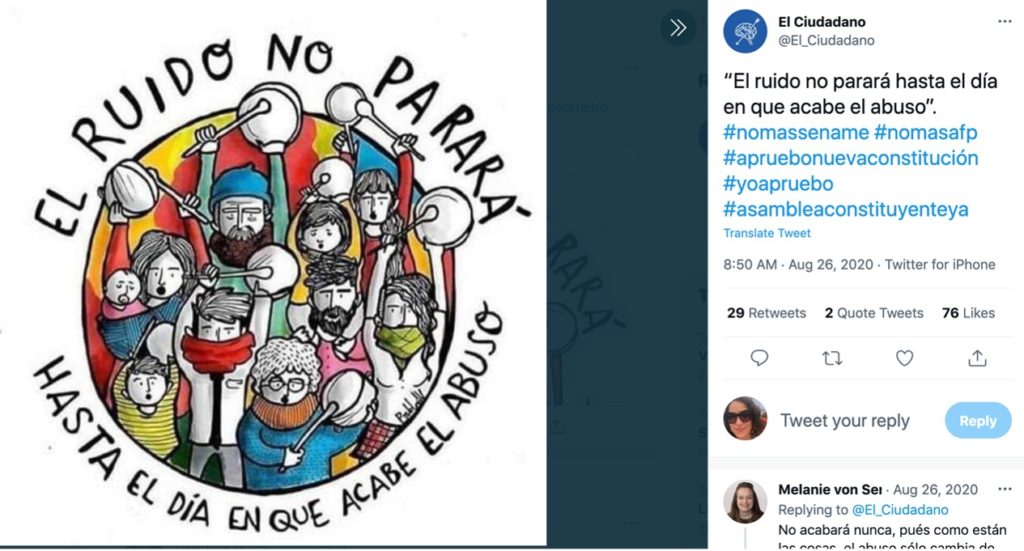

An image that circulated in social media. Here tweeted by the newspaper El Ciudadano on August 26, 2020. The text translates, “The noise will not stop until the day when abuse ends.”

Images like these have circulated widely in Chilean social networks since 2020 in a call to continue the cacerolazo’s resounding defiance, even under conditions of violent repression and the movement restrictions caused by COVID-19, including a night curfew that lasted 15 months. Such images were especially prevalent on Twitter earlier this year, as an invitation for a cacerolazo that took place on April 20, 2021 to demand the Chilean government social assistance for the population most affected by the sanitary crisis and to contest the President’s attempt at rejecting a bill that provided Chilean workers with early access to retirement funds to confront the economic crisis. This cacerolazo unleashed the accumulated anger of people who had experienced violations of their human rights during the protests and who felt that the government had used the sanitary crisis as an excuse to tame the social uprising.

A screenshot of an article with a cartoon of President Piñera facing massive cacerolazos. The headline reads: “Massive cacerolazos mark the beggining of Piñera’s public address.” Originally published in La izquierda, July 31, 2020.

Pot banging has been used as a protest practice worldwide for the past two centuries. Since the nefarious dictatorships of the 1970s, the cacerolazo became a distinctive formation of sonic political action throughout South America (Chile and Argentina are two prominent examples). Imprinted in the cultural and affective memories of twenty-first-century Chilean people, this form of non-violent protest was recuperated from the performative repertories of Chilean society to confront the measures executed by the State against its citizens. Historians and sociologists have analyzed the cacerolazo as both a popular expression and a political strategy that enables social mobilization when other expressions of discontent have been exhausted. The recent emergence of sound studies as a discipline has opened up further, sensory-based possibilities for understanding the social, political, and affective work of cacerolazos.

Insofar as sound serves to define, encroach upon, and enlarge territories, it is a means to exert power. Conversely, sound can also be used to subvert such expressions of power. The ways in which humans make presence in the world and participate in public life are deeply connected to how we make the space sound and how we listen to sound. This perspective on sound and power not only concerns people in Chile, but also other countries in the throes of public political crises, such as Colombia, Brazil, Myanmar, and the USA, where people have sustained open battles against the State to revert its monopolization of sonic control.

The principal acoustic component of cacerolazos—the metallic sounds of pots being banged—is an acoustic message of the most basic form, a non-verbal sound that urges listening. As such, these sounds place the relationship between those who sound and those who are asked to listen at the core of political debate. The sonic acts can thus challenge the political relationship between the governing and the governed. In other words, cacerolazos and other sounding political expressions are acts of conspicuous acoustic interpellation—messages that appeal to the internalized values of a given society. Through these practices people urge their governments to listen to their demands, creating a crisis of mutual recognition mediated by sound and listening. The relationship between people and state fails when no matter how loud or massive the sonic act, authorities refuse to listen. For those who emitted the message, the breakdown also indicates that the political system must be radically transformed. This is indeed what I believe has happened in Chile since October 18, 2019, when listening became radically politicized, as people voiced their discontent through different sonic acts, and instrumentalized music, sound, and listening to contest the political and juridical system.

In the aftermath of the protests, the Chilean government had no choice but to listen to popular demands. A referendum to draft a new constitution was passed on October 25, 2020, and a May 2021 election was held to elect the 155 citizens who make up the Constitutional Convention. To no surprise for those who have been listening attentively, those elected are mostly independent citizens—not the same-as-always, party-based politicians—representing wide and often marginalized sectors of Chilean society.

Plaza Ñuñoa, Santiago de Chile, October 2019. Photograph by Natalia Bieletto-Bueno.

Sonic territorialization occupies not only physical spaces, but also subjective ones. Take for example the Chilean protesters on the 2019 battlefield who resisted sonically by playing emblematic tunes that had once represented the movement of resistance against Pinochet’s dictatorial regime. And here I am not using “battlefield” as a metaphor; it was in the streets and squares and in the middle of gas bombs and gum bullets where protesters sonically resisted. A brave horn player in the streets of Antofagasta, a quena player and a saxophonist in the front line in Santiago: all resonating against the soundscape of repression. The anonymous voices that sang in the dark from balconies are another eloquent example of the emotional terrain of protest sound, as are the many concerts held in public spaces in support of the popular movement. These sonic experiences allowed listeners to engage their feelings of indignation and despair and channel them into a sense of purpose, opening up new ways to envision personal, political, and juridical transformation.

If, in traditional political theory, along the lines of Hannah Arendt or Judith Butler, to be seen in public space counts as evidence of political participation, the forms of acoustic political engagement I have discussed here demonstrate that is not only the visual, but also the sonic and audible, which constitute the confirmation of political subjectivities. As Brandon LaBelle and Salome Voegelin have argued, so long as sound and resonance incite new ways to sense and live the world we inhabit, they allow for the imagination of other possible worlds, transforming the political imagination and ultimately the actual world. This is the slippage that, as I have defended elsewhere, has changed the political subjectivities of Chilean people and that made audible their belief in the possibility of radical change.

The river of social transformation keeps on flowing, making sounds on its way. But while this idiom may situate sound as metaphor, it is the actual materiality of sound and the embodied experience of sounding and listening that has transformed the subjectivities and political participation of the people involved in this social movement. A sonic path to a dignified life has been traced: let us listen to the change.

About the Roundtable, “Protest in Latin America: 2019 and Beyond”

From Roundtable curator and Musicology Now editorial team member Felipe Ledesma Núñez:

In 2019, waves of mass protests swept the streets of Latin American cities. They were triggered by systemic inequality, corruption, and social injustice, as well as by widespread gendered violence, assassinations of social leaders and activists, and the routine violation of land and environmental rights. Throughout the social movements, sound emerged as a medium to perform and test the limits of citizenship, a means for building networks of solidarity and grassroots organizing, an element of the demarcation of power and territory, a strategic expression of resistance, and a weapon of authoritarian repression. This Roundtable, “Latin America: 2019 and Beyond,“ discusses the sonic expressions of these social movements and their ongoing legacies at local, national, and continent scales. Bringing together Latin American scholars and artists, many contributors to this roundtable will have witnessed the protests firsthand. If you are interested in contributing to the Roundtable, please contact Felipe Ledesma Núñez.