Ukraine’s Avantgarde: A Short History of a Long Tradition

The international attention Ukraine has received in the 270 days since Russia’s full-scale invasion of its sovereign neighbor is unprecedented. The world has never before shown such support for and interest in Ukrainian culture, including the world of the performing arts. Countless benefit concerts have been organized by high-profile orchestras, opera houses, and concert halls from the Metropolitan Opera in New York City to the Perth Concert Hall in Australia. Many of these events, limited no doubt by the urgency of the situation, feature the performance of frequently performed works of Western Art Music long associated with solidarity, such as the “Ode to Joy” from Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony or Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem. They also frequently include a composition by Ukraine’s most famous living composer, Valentyn Sylvestrov, who has seen the performance of his works skyrocket since February, or by Mykola Lysenko, a nineteenth-century composer and the so-called “father” of Ukrainian composition. What these displays of solidarity do not convey, however, is a sense of Ukraine’s long music history, including a deeply unique engagement with the avant-garde.

The contemporary experimentation of Ukrainian composers has gained international attention in the past decade, long before Russia’s war shed a spotlight on these individual’s lives and works. Illia Razumeiko and Roman Grygoriv, the creative composing team behind the Kyiv-based contemporary opera laboratory Opera Aperta, have already written ten operas, of which their 2018 opera-requiem IYOV was featured at Prototype Festival in New York City. Their “archeological opera” Chornobyldorf was one of the top six operas of 2021 according to Music Theatre NOW. Anna Korsun, a former participant at the Summer School in Darmstadt and the 2014 winner of the Gaudemas International Composers’ Award, has had her works performed throughout Europe and North America, while Anna Arkushyna, a former student of Beat Furrer, was recently admitted to IRCAM in Paris. I myself founded the Ukrainian Contemporary Music Festival in New York City in 2020 after being exposed to the rich tradition of experimentalism and diverse new music from Ukraine.

As each of these instances shows, the music of contemporary Ukraine is becoming well-known beyond its borders, but this progressive creativity is not a new characteristic of a young country. Many of the youngest generation of Ukrainian composers can trace their musical genealogies back to the modernist composers of the late 1910s through the early 1930s. Their own diversity of experimental approaches mirrors the variety of musical responses to revolutionary aesthetics their predecessors engaged in a century ago.

A foundational genre of Ukrainian art music is that of the art song, which acted as a vehicle for the changing musical trends from late-Romanticism to modernism. Pavlo Hunka, renowned as an operatic bass-baritone and the founder of the Ukrainian Art Song Project, argues that it is art song in particular that can challenge and disprove Vladimir Putin’s claim that Ukraine has no high culture of its own—and is, according to the Russian President, therefore no more than a territory, not a nation. Developed half a century after the German Lied tradition, Ukrainian art song has held an important space in the music of Ukrainian composers. For example, art songs constitute a substantial portion of Mykola Lysenko’s oeuvre. Their composition continued throughout the twentieth century, appearing among the works of nearly every important Ukrainian composer and canonizing the Ukrainian literary texts of Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesia Ukrainka, as well as Oleksandr Oles, Petro Karmansky, and David Burliuk.

Ukrainian Art Song Project First Summer Institute at Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, Canada. Pavlo Hunka (center) rehearsing with young artists Viktoriia Melnyk (Kyiv) and Andrew Skitko (Philadelphia, USA). Courtesy of the Ukrainian Art Song Project. Photo by Andrew Waller.

One of the genre’s modernist contributors is Stefania Turkevych (1898-1977). Celebrated as the first Ukrainian woman composer, Turkevych was a pupil of Vasyl Barvinsky in Lviv before continuing her studies in Vienna with influential professors Guido Adler and Joseph Marx. In 1925, she studied with composers Arnold Schoenberg and Franz Schreker in Berlin. When she received a PhD in musicology from the Ukrainian Free University in Prague in 1934, she became the first woman from the region of Galicia to earn a doctorate. Turkevych taught at the Lysenko Higher Institute of Music in Lviv (1935-39) and at the Lviv State Conservatory (today the Lysenko National Music Academy, 1940-44). Turkevych left Ukraine as the Soviet regime extended to Lviv in 1946 and emigrated to England, where she did some teaching and continued to compose. She died in Cambridge in 1977. Blending her training and life experience, her compositions walk a fine line between melodic folklorism and expressionist dissonance.

Turkevych’s combination of folk idioms with experimentalism is exemplified in her art songs. She crafts lyrical melodies, some of which reveal folk influences, against expressionist, pantonal harmonies. “Time Passes” (“Mynajut’ dni”) sets a text from Taras Shevchenko’s Haidamaky, an epic poem about the rebellion of peasant paramilitary groups (called Haidamaks) against oppression by the Polish nobility. The song describes what remains in a village after the withdrawal of the rebellion, including orphaned children and rotting corpses. These scenes, which took place in the late 1760s, were inscribed in poetry by Shevchenko in 1841 and were set to music by Turkevych in 1932. They bear a haunting resemblance to the photos of liberated cities all over Ukraine in 2022.

The work opens with a benign, pacing piano accompaniment that evokes time’s passage—“days pass, summer passes”—before the solo piano, taking melodic and metric liberties in a short interlude, grows in intensity towards the next line of text: “Ukraine, hear me, is burning.” As the text describes children crying for their missing parents, the accompaniment cedes into the background, echoing the simple melody of the singer. The description of whispering leaves is set to a slow triplet melody, that rocks the listener not so much to sleep, but something more like catatonia. An image in the text, “The human tongue is nowhere heard,” is accompanied by an emotionless, hollow drone in the piano, while the singer intones on a single note. The music draws parallels between a howling beast and the smell of the corpse, both of which occur upon entry to the village. The final coda returns to the steady sounds of the haunting opening as the singer repeats: “days pass, days pass, summer passes.” (Recordings of all of Turkevych’s songs, as well as transposable scores with transliterations and translations are available free of cost through the Ukrainian Art Song Project.)

Though the genre had not previously occupied Ukrainian composers, symphonic composition exploded in early twentieth-century Ukraine. (Lysenko, for example, composed only a symphonic fantasia and never finished his work on a symphony.) Two of Ukraine’s most important contributors to the genre are Lev Revutsky (1899-1977) and Borys Liatoshynsky (1895-1968). Their compositions show Ukrainian engagement with impressionism, post-romanticism, and expressionism. Revutsky was born in Irzhavets, a village north of Kyiv, while Liatoshynsky hailed from the transportation hub of Zhytomyr. Both studied in Kyiv with Reinhold Glière, the Kyiv native who was among the National Music Academy of Ukraine’s first professors and directors. Both composers spent their careers as professors based at the National Academy of Music in Kyiv, though Liatoshynsky taught at Moscow Conservatory (1941-44), and Revutsky headed the composition department at Tashkent’s music conservatory.

Revutsky’s Symphony No. 2 (1926-27) is lyrical, constructed almost entirely from folk melodies, but transformed into a thoroughly post-romantic symphony through the use of impressionistic washes of sound. Folksong quotations permeate the work like a kind of cantus firmus, a unifying repeated melody that has structural importance to a piece of music. According to the composer’s own notations in the score, each of the symphony’s three movements integrates folk melodies recorded by the composer himself as well as the Ukrainian ethnomusicologists Klyment Kvitka, Mykola Kolessa, and the composer’s brother, Dmytro Revutsky. The combination of folk elements with well-established formal conventions, such as sonata and rondo forms, elevates Ukrainian folk music into the realm of art music composition. As such, Revutsky created a musical equivalent to the paintings of Ukrainian modernists, combining folk sources and imagery within “learned” frameworks.

By contrast, Liatoshynsky’s Symphony No. 2 (1935-6), also in three movements, navigates a space between late-Romanticism and bombastic expressionism reminiscent of Gustav Mahler. In an essay on Liatoshynksy’s symphonic compositions, Ukrainian musicologist Dina Kanievska aptly described the Second Symphony as revealing “the rift between beauty and cruelty.” The composer intelligently emphasizes the range of orchestral colors, often drawing a single timbre out of the mass of sound. The symphony’s first two movements never quite escape a sense of foreboding, amplified through agitated passagework in the first movement and a basset horn solo in the second. The finale, however, breaks through with a late-Romantic burst of striving, complete with full employment of brass and percussion sections. The work was completed in 1936 and, like the infamous review in the Soviet paper Pravda that condemned Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady MacBeth of Mtsensk for being “muddle, instead of music,” Soviet censors branded Liatoshynsky’s symphony as “formalist” and banned it from performance.

Seated, left to right: Valentyn Sylvestrov and pianist Yevhen Rzhanov; Standing, left to right: Borys Liatoshynsky, Yuri Kholodov, Oleksandr Kravchuk and Borys Skvortsov, and Leonid Krasnoshchok, members of the Lysenko String Quartet. From Borys Liatoshynsky: Memories. Letters. Materials, 1986.

Both symphonic composers, unique in their approaches to the symphonic genre, have inspired Ukrainian composers for decades. Liatoshynsky and Revutsky were important pedagogues at the Kyiv Conservatory and their students included members of the “Kyiv Avant Garde” such as Valentyn Sylvestrov and Leonid Hrabovsky. Shortly following Ukraine’s independence in 1991, the American-Ukrainian conductor Theodore Kuchar undertook a project to record all of Liatoshynsky’s symphonies with the Ukrainian State Symphony Orchestra. Most recently, Revutsky’s Second was performed by the Kyiv Symphony Orchestra as part of a special Independence Day concert in Gera, Germany, where the orchestra has taken up residence.

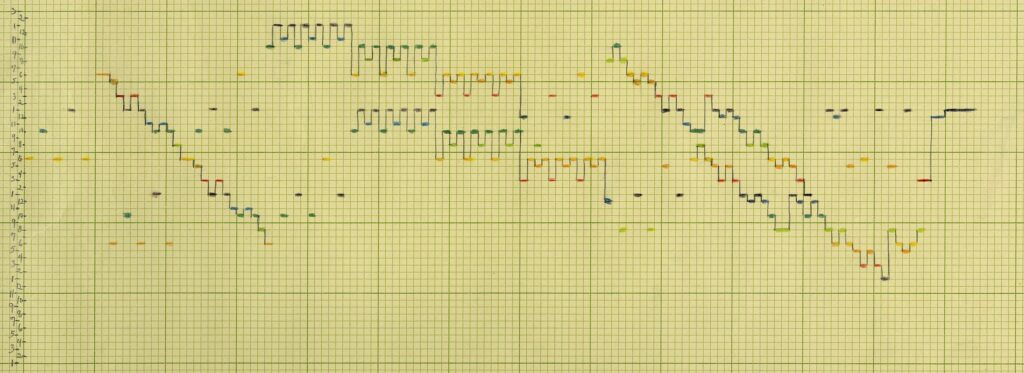

Experiments of a different kind took place in Kharkiv, the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic from 1922 to 1934. Following Ukraine’s absorption into the Soviet Union alongside the implementation of Ukrainization policies, Kharkiv was a rich center of modernist experimentation across the arts, from theater to literature. Joseph Schillinger (1895-1943) began developing his Schillinger System of Composition, a complex approach to musical composition based on mathematical relationships, while in Kharkiv during during this time. Schillinger’s new system of sound organization was based on geometrical phase relationships that were applied to elements of melody, harmony, and especially rhythm, as well as orchestration, graphic design, and other art forms. (Some of Schillinger’s visual “kinetic art” is held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.) The composer’s early mathematical approach to sound organization can be seen in his expressionist Five Pieces for piano from 1923. (Here is a YouTube link of a MIDI performance of the work, an interesting realization of the music given Schillinger’s own advocacy for automated performance.)

Chart by Joseph Schillinger graphing Johann Sebastian Bach’s Invention no. 8 in F Major, BWV 779. Courtesy of the Music Division, The New York Public Library.

Born in Kharkiv, known as Ukraine’s second city after Kyiv, in 1895, Schillinger taught composition at the Kharkiv Music and Drama Institute (today the Kharkiv Conservatory) and served as Head of the Music Department of the Ukrainian Culture Ministry (1918-22), following his studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. He was principal conductor of the first Ukrainian Symphony Orchestra in 1920-21. In addition to teaching and performing, he was deeply engaged in Kharkiv’s cultural life, giving concert introductions, presenting poetry readings, and composing music for theater, including the 1921 production of Hercules’ Heroic Deeds for the Imperial Theater for Children, predecessor of the now-famous Kharkiv Theater for Children and Young Adults. After a brief period in Leningrad, during which he organized the first jazz band concert in the Soviet Union, Schillinger emigrated to New York City in 1928. There he made significant contributions to American musical life as a professor at the New School for Social Research, New York University, and Columbia Teachers College—his students included Vernon Duke, Tommy Dorsey, George Gershwin, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Henry Cowell and others. His composition method attracted B.B. King and Earle Brown. According to Ben Ratliff’s biography of John Coltrane, the legendary musician owned a copy of Schillinger’s Kaleidophone: Pitch Scales in Relation to Chord Structures, the only work of Schillinger’s theories published during his lifetime. Berklee professor of Jazz Composition Ted Pease has even argued that Schillinger’s writings may have influenced the composition of Coltrane’s Giant Steps. Schillinger became an American citizen in 1936.

Schillinger was interested in many forms of musical innovation, including novel musical instruments. He befriended Lev Termen, who invented the theremin, in the United States. The Ukrainian composer’s First Airphonic Suite, premiered in 1929 by the Cleveland Orchestra with Termen himself playing the theremin, is a neo-Romantic piece and one of the first compositions for the electronic instrument. Some of Schillinger’s experiments with rhythm were realized on the rhythmicon, designed by Henry Cowell and built by Termen. As Cowell described it in New Musical Resources, the eletro-mechanical instrument could generate pitches and rhythms, leading Jean-Michel Reveillac to dub the rhythmicon the first drum machine. Although Schillinger’s aesthetics differ from those of Turkevych, Revutsky, and Liatoshynsky, he, too, was an active participant in the new discourses on music in the 1920s.

Even brief introductions to these four figures in Ukrainian musical modernism show an astonishing breadth of creativity and a long-standing interest in the aesthetic cutting edge that I hear as continuous with Ukrainian art music today. The musical aesthetics of Ukrainian composers are still as rich and diverse as they were in the 1920s and 30s, engaging new composition methods, instruments, genres, and messages. While there has been significant study of Ukrainian modernism in literature, drama, and art, the musical activity and repertoire of this period still remains largely unknown outside Ukraine. An opportunity presented by Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine is to invest in more than just solidarity with Ukrainians, but to better know, understand, and share Ukraine’s rich tradition of artistic experimentation dating back more than a century.

About the Roundtable, “Musical Lives of Ukraine”

This post is the second of a three-part roundtable, “Musical Lives of Ukraine,” commissioned after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia on February 24, 2022. The roundtable participants open worlds of musical life past and present in Ukraine, writing out of their experiences of music and Ukraine during the war. The first post is Oksana Nesterenko’s “Kyiv’s New Music Scene Today.” For more on music and the war in Ukraine at Musicology Now see: “Music from Ukraine: A Collaborative Portrait Gallery in March 2022” and Adriana Helbig’s “Ukraine’s War-Time Pianos and the Sounds of Resistance.”