“Welcome to the Sound Wellness Revolution”: Endel’s AI-Generated Soundscapes and the Commodification of Passive Listening

In January 2019, Warner Music Group signed a twenty-album contract with the artist Endel. And then in May 2023, Endel came to an agreement with Universal Music Group to collaborate with the label’s artists. These major record label deals would be impressive under any circumstances, but what’s most striking is that Endel is not a living artist—it’s AI.

Endel, a German company founded in 2018, has been described as “the first-ever algorithm to sign a deal with a major label.” Unlike music companies that use generative AI to write new songs, Endel is a standalone subscription service (currently 14.99 USD/month) that uses AI to create ever-shifting “wellness soundscapes” that dynamically adapt to information such as the weather, time of day, and listener’s heart rate. The app belongs to a growing number of companies (including Brain.fm and Focus@Will) that claim their music will boost productivity, decrease stress, improve sleep, and benefit overall mental health. While these services aim for universal appeal, their marketing especially targets listeners drawn to self-improvement and self-optimization.

Endel’s introductory video

In recent years, so-called “functional music” has become increasingly popular in the Global North, generating millions of dollars for the music industry. But under the veneer of wellness and appeals to questionable science, functional music companies like Endel bring into focus broader concerns about outsourcing creative labour to AI and exploiting self-care for profit. These concerns challenge us to be conscious of how our listening practices may benefit corporations that derive value from the passive consumption of music, potentially perpetuating inequitable structures for musicians and listeners alike.

Mood Music: The Rise of Passive Listening

Functional music is nothing new. From work songs to workout playlists, music is often used to influence listeners’ moods and behaviours. This is exemplified by the ubiquity of background music, which can be traced to the United States in the 1930s when the company Muzak first began piping easy-listening music into stores, workplaces, public transit, and other spaces. In the century since, recorded background music has spread throughout much of the world from Britain to Japan, designed to calm listeners, encourage customer spending, and increase worker efficiency. These effects reflect Anahid Kassabian’s concept of “ubiquitous listening,” which describes how even passive engagement with music can shape affect and subjectivity.

Now, it’s increasingly common for individuals to control their own musical environments through smartphones and other devices, as documented by Michael Bull, Tia DeNora, and Mack Hagood. In recent years, mood- and context-based playlists on music streaming services like Spotify have become immensely popular and there has been a boom in ambient music. Millions of listeners now passively stream music as they study, exercise, cook, meditate, clean, and even sleep. Liz Pelly and Paul Allen Anderson identify that this functional use of music bears a resemblance to Muzak in its potential to regulate affect through “lean-back” listening.

Building on the popularity of passive listening practices, functional music companies like Endel take things a step further by offering personalized soundscapes that target specific goals. Endel’s current soundscape offerings include “Focus,” “Relax,” “Move,” “Study,” and even “Intimate Connections.” What’s more, the company promises that its AI will adapt these soundscapes in real time to optimize their efficacy. But what do these soundscapes sound like, and is their science sound?

Sound Science? Endel’s Endless Soundscapes

The musical content of Endel’s soundscapes, created by sound designers and artist collaborators, generally lies at the intersection of New Age and ambient electronic. In the “Focus” soundscape, for instance, shimmering synth pads and subdued drum machines swell and fade as the harmony gently meanders from chord to chord in entirely diatonic movements. The music is, by design, inoffensive and easily ignorable. Endel’s co-founder and Lead Sound Designer Dmitry Evgrafov claims that “listeners may . . . notice that the AI-powered soundscapes are often very simple. Using less complex tones, melodies, and movement helps ease the burden on our minds.” The aim is not to listen to the music, but to let the music do its work on you, whether that means entraining you into a productive flow state or gently lulling you to sleep.

A twenty-minute version of Endel’s “Focus” soundscape

What distinguishes Endel from its competitors is that its soundscapes are endless and use generative AI to adapt to contextual information such as time of day, weather, movement speed, and heart rate. For example, the music will pick up pace if you move faster, and the intensity of the beat will vary as the day cycles through energy “rises,” “peaks,” and “rests.” Endel’s “manifesto” describes the service as a “tech-aided bodily function,” suggesting that “none of the essential bodily functions require manual activation . . . responses happen and adjust to the situation without any conscious effort. In a similar way, Endel takes in various internal and external inputs and creates an optimal environment for your current context, state, and goal.” As sound studies scholar Maren Haffke argues, Endel “promises to mediate digital infrastructures as adaptive environments by framing subjectivation as a synchronization of technical and bodily processes in ‘real time.’”

Like many other wellness and productivity products and services, Endel appeals to “scientific principles” supposedly based on neuroscience and psychoacoustics to back its claims. This participates in a long history of companies using “scientific research” to demonstrate music’s effects on listener behaviour. In the 1950s, for example, Muzak’s (pseudo)scientific research led to the “Stimulus Progression” system, designed to maximize worker productivity by programming background music into fifteen-minute blocks based on patterns of musical intensity. This is paralleled by Endel’s “energy cycles,” which are apparently based on circadian rhythms. There is likely some truth to functional music’s efficacy—there is evidence, if inconclusive, that background music can improve focus, sleep, and mental health—but the science is less clear-cut than companies like Endel suggest. Endel’s main reference, for example, is a non-peer-reviewed white paper conducted by the AI company Arctop and partially funded by Endel itself.

Furthermore, functional music’s effects are not necessarily positive. Scholars such as Jonathan Sterne, Simon C. Jones, and Thomas G. Schumacher have argued that background music can be a mechanism of social control in capitalist societies used to manipulate consumer behaviour. Anderson similarly contends that the “neo-Muzak” of streaming services often makes unpleasant working conditions more tolerable instead of enacting systemic change. In that sense, Endel’s wellness soundscapes may treat the symptoms of a stressful society that drives people toward maximizing their productivity rather than taking steps to provide an actual cure. However, the real incentive behind Endel’s technology is arguably not its effects on listeners, but rather its ability to generate economic value through AI and passive listening.

Man or Machine? The Commercial Potential of AI-Generated Functional Music

There are clear financial incentives for AI-generated functional music. With AI, companies like Endel can create an abundance of music quickly and at an unprecedented scale. They can also bypass having to license individual tracks on a playlist and thus avoid paying royalties to numerous musicians and other rightsholders. When the goal is to create music that is heard but not listened to, an endless AI soundscape may be just as effective as a Spotify playlist consisting of several distinct recordings by multiple artists. Endel has clearly convinced others of its value, securing deals with major record labels and raising tens of millions of dollars in venture capital from investors such as the Amazon Alexa Fund, Wavery Capital, and True Ventures.

But AI technology can also bring in money for artists. Many of Endel’s soundscapes were designed by notable musicians, including James Blake’s “Wind Down,” Miguel’s “Clarity Trip,” Plastikman’s “Deeper Focus,” and Grimes’s “AI Lullaby.” In addition to bringing star power to the service, these collaborations point to the profound commercial potential of functional soundscapes for artists—something that Endel explicitly markets to labels.

Richie Hawtin (a.k.a. Plastikman) discussing his collaboration with Endel

Endel advertises that its AI technology can be used to create “companion releases” of albums and repurpose older catalogue recordings into new soundscapes. Since October 2023, Endel has announced that it will be creating fifty wellness albums with electronic artists from Warner’s Spinnin’ Records label and has already released several soundscapes based on Roberta Flack’s 1973 recording of “Killing Me Softly with His Song” and WAR’s 1972 album The World is a Ghetto. The artist 6LACK, whose 2023 album Since I Have a Lover recently received the Endel treatment, says that “knowing you can take the stems of what I’ve already created and feed them into an algorithm and pick whatever aim you want for it—whether it’s sleep or relax or study—and then the system analyzes the stems and reconstructs it and generates a soundscape… it’s like magic. It’s technology, but it’s art and it’s magic.”

An Endel video advertising its creative opportunities for artists and labels

While Endel’s main offering is its standalone subscription app, its soundscapes are also packaged as dozens of albums on services like Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube where they’ve collectively accrued millions of streams. These albums are often strategically divided into several short tracks that are mostly identical, thereby generating more royalties as listeners stream them in the background. Endel’s soundscapes are designed to be played everywhere, all the time: the service is integrated into consumer electronics, cars, airplanes, workplaces, stores, and more. The company boasts that it has “1 million active users monthly, and they listen to a million and a half hours a month.” In an attention economy where businesses across entertainment industries vie for finite user attention, music’s ability to be listened to passively as a supplement to other activities makes it especially lucrative.

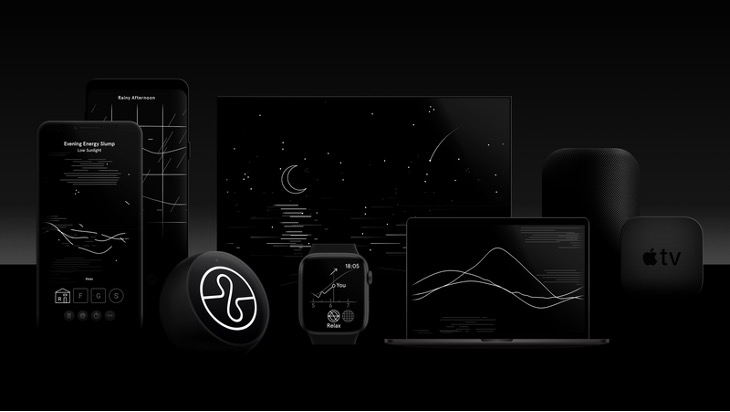

Endel’s product ecosystem and integrations (Image by Ch3rn1k. Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Indeed, on streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music where rightsholders are remunerated based on the amount of streams they receive, more listening equals more royalties. Functional music is particularly profitable on streaming services because it is designed to be streamed continuously in the background to maintain its effects. In response to the rapid influx of “functional genres” like white noise and nature sounds, Spotify announced a new royalty model in November 2023 that reduces payouts for functional music. Endel’s Chief Commercial Officer Marina Guz tells CNN that “obviously white noise is very different from ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ but it, currently under this model, is paid the same. . . . There’s been an ongoing conversation this entire year of the value of music and how something like someone just putting up white noise is different than paying for an artist that had spent a year in the studio making the album with all kinds of instruments and people involved.” Endel’s own soundscapes seem to straddle this line: they often work directly with artists but generate massive amounts of new content from pre-existing music.

Endel stresses that it supports artists, differentiating itself from the endless white noise and nature sounds on streaming services. But it’s also easy to imagine AI automating most functional music in the future. AI-generated music has already started flooding streaming services at an alarming rate. Spotify itself was embroiled in a “fake music” scandal a few years ago when it was accused of stacking official mood playlists with its own artists to save on royalty payments; with good enough AI, you wouldn’t need the artists at all.

From “fake Drake” to algorithmic recommender systems, artificial intelligence has dominated recent music industry discourse. Many enthusiastically embrace the efficiency and creative potential of AI, while others claim that it infringes on copyright, perpetuates biases, and redirects royalties from content creators to corporations. Endel’s soundscapes are certainly a less flashy use of AI—arguably by design—but bring into focus the ways that musical labour is changing in response to new technologies and listening practices.

Studying Endel pushed me to reflect on my own listening. Like many others, I often stream music in the background throughout the day while I work, do chores, and relax, typically through Spotify. Anecdotally, when testing Endel I found the “Focus” soundscape was generally pleasing and occasionally helped me get “in the groove” when writing (including this article!). However, in an age where platforms harvest granular user data and artists’ livelihoods are predicated on stream counts, listening is never a neutral act. What we choose to listen to, and how we listen to it, has economic, cultural, and even environmental consequences. I am by no means suggesting that passive listening is inherently “worse” than active listening, but rather arguing that we should pay attention to how our listening habits implicate us in structures designed to extract value from passive engagement.

In many ways, functional music companies like Endel are just the latest in a long line of services that promise to harness the benefits of music, whether that be for productivity, (self-)care, or even childhood development. This is not to say that these services are without advantages; many listeners attest that functional music and soundscapes noticeably enhance their mood, productivity, and wellbeing. Several artists who have collaborated with generative AI companies have also praised the technology for opening up new creative and economic opportunities for musicians, something that cannot be overlooked in an increasingly competitive music industry. But amidst fears of AI replacing human artists and the troubling trend of commodifying wellness, we should critically examine the ways that digital platforms are profiting from passive listening practices and mediating our relationship to sound and self. Because if this is the “sound wellness revolution,” who do you want leading the charge?