Sin perreo no hay revolución: The Day Reggaeton Became Puerto Rico’s National Music?

Protesters chanting “Ricky Renuncia” outside the Governor’s Mansion during summer protests of 2019 in Puerto Rico. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Alcaraz.

On July 24, 2019, Puerto Rico, “the oldest colony in the world,” achieved the unimaginable in ousting Governor Ricky Rosselló from office. In an unprecedented manner, the social movement known as “Ricky Renuncia” (Ricky Resign) united people across generations, sexualities, social class, political, and religious ideologies. The public backlash against Governor Rosselló was ignited by leaked information from a private chat between him and members of his cabinet, which contained vulgar, racist, and homophobic remarks. The protests began on the 14th of July with hundreds chanting Ricky Renuncia to the beat of clanging pots (cacelorazos) outside La Fortaleza (the Governor’s Mansion) in San Juan and quickly gained momentum. Days later a colossal march of 700,000 repeating “Somos mas y no tenemos miedo”—“We are more and not scared”— halting traffic on Puerto Rico’s main highway.

Popular music and dance in Puerto Rico have long standing histories of being politicized. Genres now considered symbols of Puerto Rico’s national identity such as bomba, danza, plena, jibaro music and salsa, have at some point been used to articulate and subvert state power. And though these musics again played crucial roles in voicing public indignation against Rosselló, it was surprising to see reggaeton music and dance rally the crowds to protest during the most emblematic moments of the 2019 uprising. Surprising because with some exceptions reggaeton has mainly sought to mobilize people to the hedonistic world of the night club than to the picket line.

Despite its fame as an internationally acclaimed popular music and its wide appeal to consumers across social class and race, in Puerto Rico reggeaton is still associated with the predominantly Black and marginalized people of the hood (caserio), the violence and drugs of the underworld. Furthermore reggeaton isn’t yet disentangled from the social controversy and censorship that it provoked in its early days among certain politicians, including Pedro Rosselló (Ricky Rossellós father) and conservative factions who demonized the genre for its profuse usage of vulgar language, the misogynous portrayal of women, and its hypersexualized dance known as perreo (doggy-style grinding). Thus, the use of reggaeton as a tactic of subversion on a national level in 2019 was unprecedented and reveals the significant impact that younger generations had in the Ricky Renuncia movement. Moreover, it highlights the heavy irony and poetic justice of reggaeton as a revolutionary tactic which revendicates “the marginalized and degenerate dance of the caserio” as a way to expose the corruption, misogyny and racism of Ricky Rosselló and his government.

Protesters performing plena music during the summer protests of 2019 in San Juan. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Alcaraz.

Although Ricky Renuncia was in essence a grassroots movement, many of the demonstrations were led by reggeaton icons Residente and Bad Bunny—and other artists who amplified the anti-Rossello sentiments circulating on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) and placed the Ricky Leaks scandal on the radar of international media outlets. In a July 18 interview from just beyond the gates of La Fortaleza, an angry Residente explained his understanding of the uprisings’ root cause and expressed general indignation: “It’s not about the chat, it’s how they’ve treated us. They have been fucking us for years. This isn’t the only government that has screwed us, but this government put the last drop that spilled the cup, they really did.” While the drama escalated on the streets of San Juan with the governor showing no signs of conceding, Residente and Bad Bunny channeled the resentment of the people into a new musical release, “Afilando Cuchillos”—“Sharpening the Knives.” As a diss track aimed at Rosselló, “Afilando Cuchillos” chronicles years of government corruption and details the issues that lead to the 2019 protests. Among the factors are the austerity measures imposed by the Oversight Board, fraud and embezzlement charges made against Rossello’s top officials, tax exemption policies for foreign investors, the privatization of public agencies, and the poor management of the 2017 Hurricane María crisis. The track was transmitted live on huge loudspeakers at a march held on July 17 that mobilized over 500,000 thousand people. Residente and Bad Bunny sang along with the crowd, often interjecting the songs most memorable phrases: including “Dale la bienvenida, a La generación del Yo no me dejo!” ”—”Welcome the generation of ‘I’m not taking it!’”

A music video for “Afilando Cuchillos” with footage from the protests.

The march on July 17 and “Afilando Cuchillos” struck a chord of national pride and especially engaged the generation del yo no me dejo. The perreo combativo, a combative reggaeton dance, on July 24 was the culminating event of the protests. The perreo, which I describe in detail below, created a lot of hype and controversy both before and after the demonstration. On that night, with multitudes outside his mansion grinding to the beat of reggeaton, Rosselló finally announced his resignation on the government’s official Facebook page. Images of jubilant crowds in San Juan chanting “Olé Olé Olé Olé” and singing the reggaeton hit “Te bote” (“I dumped you”) circulated on the news and social media, confirming the outcome. While some hailed the perreo as a decisive blow to Rossello’s downfall, others criticized the event as “a joke” (un relajo) or a “good time” (vacilón), implying that it was a mockery of the sacrifice of those who had been protesting in the front lines, taking blows and tear gas from the police. Moreover the perreo also provoked harsh criticism from religious groups who condemned dancing reggaeton in front of the San Juan Cathedral as a repudiable act.

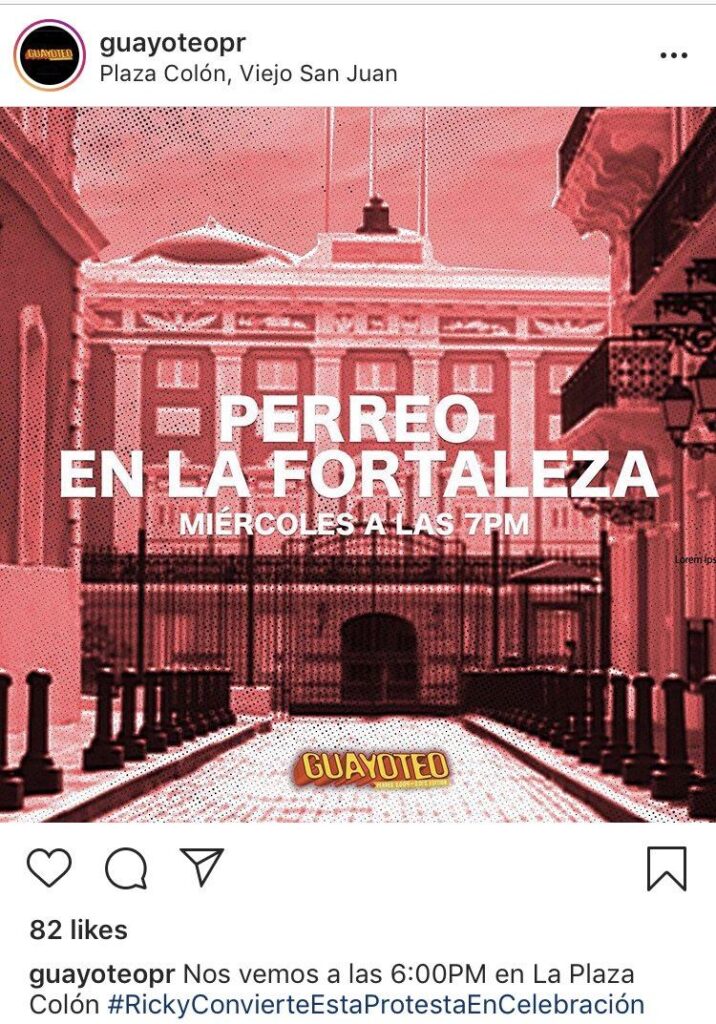

Screenshot of GuayoteoPR announcing the July 24 perreo on Instagram.

As a subversion tactic, the perreo combativo mobilized and incorporated divergent constituencies on the political stage. It was initially conceived by the group GuayoteoPR, who announced “Perreo en la Fortaleza” (Grinding at the Governor’s Mansion) on their social media pages on July 23. The post went viral and gained credibility when Pop star Tommy Torres and politician Manuel Natal, among others, confirmed they would be grinding at Fortaleza. “We want to take the message in different ways. There is a generation that grew up with plena, another with salsa and this generation that is leading the protests grew up with reggeaton,” read a press release by GuayoteoPR.

During the perreo, Guayoteo’s MC Auudi Robles chanted “Ricky Renuncia el pueblo respeta este perreo es de protesta (Ricky Resign respect the people, perreo is protest)” to a crowd of 6,000. Afterward, Auudi commented that the perreo had surpassed the group’s middle class fan base and admitted that the event got out of hand. He recalls people grinding in the streets, on top of cars, womens’ behinds pressed up against car windows. DJ Kelvin el Sacamostro, a respected figure in the underground reggaeton scene from the local caserio of Llorens Torres (housing project), also participated in the perreo.

While Guayoteo and DJ Kelvin had people twerking “bien duro y hasta abajo”—“hard and to the ground”—close to La Fortaleza and in Plaza de Armas,the central plaza, the LGBTQ+ community held a perreo of their own on the steps of the San Juan Cathedral. DJ Kayaté, a recognized artist in Puerto Rico’s queer community, recalled to me her uneasiness with performing perreo in front of the Cathedral to a crowd that did not fully understand their agenda and criticized this act of resistance as a “freak show,”—a paraphrase of their slurs that Kayaté offered in interview with me. The scene of queers grinding, some with little clothing, on the steps of a Cathedral draped with posters that read “Soy pata, puta, pero nunca corrupta” (I might be lesbian, and whore, but never corrupt) quickly drew the spotlight.

The July 24 perreo combativo on the steps of the San Juan Cathedral.

For Kayaté, perreo is a form of resistance that embodies hayaera, a feeling of freedom and liberation. This perreo combativo was a form of protest not only aimed at Rossello and his government, but against all the institutions that have historically condemned queer bodies and sexuality, Kayaté elaborated in conversation with me.

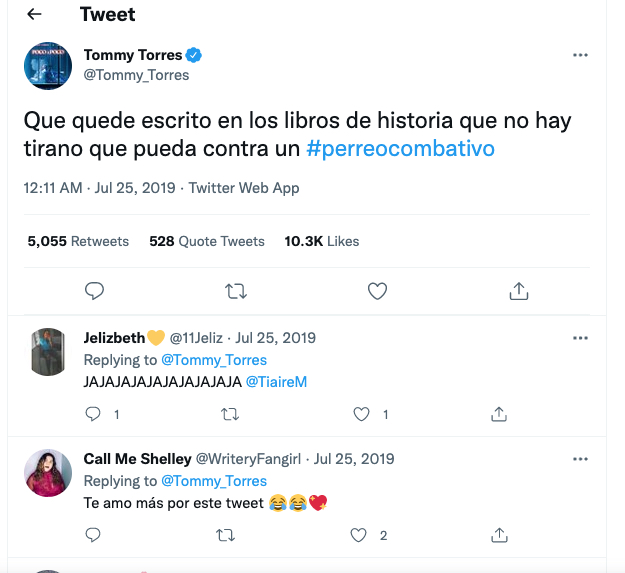

The images of couples grinding and booty shaking in different parts of a city turned upside down by revelry and carnivalesque behavior drew a lot of attention. A long feed of meta social internet commentary created drama concurrent with the live protest. Some celebrated perreo as a form of resistance, others condemned the dancing protest mode as offensive and irreverent. Adding to the mythical aura of the event, singer songwriter Tommy Torres tweeted the day after Rossello’s resignation: “Let it be written in the history books that no tyrant can withstand a perreo combativo.”

Screenshot of Tommy Torres’s viral tweet.

There is a certain irony to Torres’s statement regarding the perreo, but Black music and dance in Puerto Rico have long-standing histories of being subversive. Between the sacred and the profane, between the serious and the ludic, dance and the body have been sites to explore freedom and citizenship, alternative sexualities, and political stances that “lie outside governmental control.” Reggaeton, and especially perreo, as expressions seen as inherently vulgar, degenerate, and anti-establishment were strategically used during the protests to expose the very corruption of which they have been accused. This paradox was best exemplified in the perreo combativo on the steps of the San Juan Cathedral, where the public display of semi-naked bodies and specifically self-identified queer bodies grinding on grounds considered sacred made a profound political statement.

The revolutionary character of perreo combativo and reggeaton lies in its power to mobilize and actively engage diverse groups (the LGBTQ+ community, middle and upper-class youth, marginalized minorities) and invite non-political actors onto the political scene. Younger generations and the queer community in Puerto Rico have adopted the slogan: “Sin perreo no hay revolución”—“Without perreo there is no revolution.” Though reggaeton may never be officially considered a national music in Puerto Rico, during the summer protests of 2019 it was the music that pulled the nation together.

As the “reggaeton nation” continues to grow in Puerto Rico, its diaspora, Latin America and other parts of the world, could reggaeton provide spaces to further explore social topics (gender, sexuality, social commentary) and empower youth and queer communities? Can perreo combativo become an alternative mode of pacific resistance and revolution for other countries in Latin America? As reggeaton and perreo show no sign of slowing down, these questions will surely be debated heatedly in the years to come.

About the Roundtable, “Protest in Latin America: 2019 and Beyond”

From Roundtable curator and Musicology Now editorial team member Felipe Ledesma Núñez:

In 2019, waves of mass protests swept the streets of Latin American cities. They were triggered by systemic inequality, corruption, and social injustice, as well as by widespread gendered violence, assassinations of social leaders and activists, and the routine violation of land and environmental rights. Throughout the social movements, sound emerged as a medium to perform and test the limits of citizenship, a means for building networks of solidarity and grassroots organizing, an element of the demarcation of power and territory, a strategic expression of resistance, and a weapon of authoritarian repression. This Roundtable, “Latin America: 2019 and Beyond,“ discusses the sonic expressions of these social movements and their ongoing legacies at local, national, and continent scales. Bringing together Latin American scholars and artists, many contributors to this roundtable will have witnessed the protests firsthand. If you are interested in contributing to the Roundtable, please contact Felipe Ledesma Núñez.

Read the previous posts in this roundtable: “Sounding the Path to Dignity: Chile after October 2019,” by Natalia Bieletto-Bueno, and “The Eloquence of Noise: The Cacerolazo in Colombia Since 2019,” by Juan Fernando Velásquez.