The Eloquence of Noise: The Cacerolazo in Colombia Since 2019

For some readers, the word “protest” and the sounds of banging pots might call to mind Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020, the attack on the US national capitol on Jan 6, or the scenes of people banging pots and pans as positive public expressions of support for health workers in spring 2020 in, for example, New York City. However, social unrest also has intertwined sound and protest beyond North America of late. In this essay, I turn to the Colombian cacerolazo to offer a global perspective on the ways that noise has become an eloquent means of expression to public outcry and unrest before, after, and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2019, the economic discontent of disenfranchised urban middle classes, fury over political roguery, and the influence of other protest movements like the yellow vest protests in France, the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, and #metoo online shook communities globally. This wave of upheavals also reached Latin America. In Colombia, it has continued in a series of uprisings articulated around distinct grievances directed against President Iván Duque’s administration. Protests began when the country’s two largest labor unions called for a nationwide strike to oppose new reforms to national social security. The strike grew to an unprecedented scale when students, cultural associations, Indigenous groups, Afro-Colombians, LGBTQ+ communities, feminist collectives, and environmental activists joined forces with the unions. Together, they established a committee and proceeded to invite citizens through social media to participate in the strike.

On November 21, 2019, more than 200,000 Colombians attended non-violent marches in Bogotá, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, Cartagena Manizales, Medellín, Cali, Popayán, Pasto, and elsewhere. However, after 5:00 PM the protests went awry when the Colombian National Police clashed with protesters. At 7:00 PM, local authorities enacted curfews in several cities. At 8:00 PM, people responded to the curfews by banging pans from their homes, standing on their balconies and doors so that the sound would be heard. As reported on the news soon thereafter, thousands of Colombian citizens had sounded their rage and frustration through the first national cacerolazo. Noise intruded into public spaces, shattering the institutional fantasies of social control embodied by the emptied and silenced streets.

Coverage of the cacerolazo by CNN Español on November 22, 2019. This video shows different aspects of the protests in Bogotá and México City. The latter was organized by members of the Colombian diaspora in this city.

Cacerolazos, protests in which people bang pans and pots, can be traced as far back as the French protests opposing the July monarchy in 1830. They have since been employed in contexts as distant in space and time as Algeria (1961), Canada (2008), Iceland (2008), Turkey (2013), Spain (2020), and Thailand (2021). Latin America plays a central role in this global lineage of noise and protest, as the cacerolazo has become the common expression of dissent within the social uprisings across the region. As Natalia Bieletto-Bueno has pointed before in this Musicology Now roundtable, historians often recognize the notorious 1971 March of the Empty Pots as the first Latin American cacerolazo, which later spread throughout the region in the 1980s and 90s.

Since the late twentieth century, Latin American social uprisings have responded with animosity towards political corruption, neoliberal policies, political figures, and the lack of effective political and institutional responses to unequal wealth and resource distribution. However, since the 2000s, the use of social media to summon citizens and the crisis of traditional political parties extended the social scale of the protests, while the cacerolazo’s low-stakes and participatory nature has invited historically non-political actors.

In the Colombian case, two issues have further contributed to unprecedented participation of people who have not publically engaged in politics in the past: (1) the alarming increase in the murders of social and environmental leaders; and (2) how different political actors and governmental policies have jeopardized the 2016 peace agreement. The latter issue encapsulates: the government’s slow and tortuous implementation of the accord between the state and the FARC guerrilla, the attempts of the government and its political allies to reform the transitional justice system, the participation of former FARC commanders in international drug-trafficking, and the fleeing of former FARCs’ members to create a new guerrilla.

Many Colombian citizens believe that the cacerolazo was a “spontaneous,” “massive,” and “nonpartisan” protest in response to concerns about these issues and because of the generalized rejection of Iván Duque’s government and violent actions by some enraged protesters and enforcement officers during the events of November 21st. This view has also persisted on social media. For example, Silvia Montilla, a young woman who participated in the cacerolazo, was interviewed for City TV, a local television channel. She said: “Many people of different ages joined [the cacerolazo], from children to the elderly, because we are tired of this government.” In the same interview, an unidentified middle-aged man declared: “This [cacerolazo] is [making] history. In my whole life, I never had witnessed a protest as massive as this one; you can see parents, children, and families [protesting around us].”

A screenshot of the Colombian national strike coverage by CNN Español. The title summarizes the series of events that unfolded on November 21, 2019: “Protests in Colombia: Unrest, Tear Gas, Cacerolazo, Curfew, and Closed Borders.”

As these statements from the cacerolazo exemplify, protesters understood that they were participants in a diverse—if fleeting—community. Within such sonic communities, protesters become agents who, as Benjamin Tausig has argued, shape multiple, ephemeral, and changing clusters of sound by adapting local and global ecologies of political expression to the logic of social dissent. In this case, the noise of empty pans coming from streets and homes not only disrupted the enforced silence but blurred the borders separating private from public spaces to overcome fear, joining people from different ages, social classes, and political affiliations. Caceroleros—those who participate in the cacerolazo—were not the passive figures Michael Birenbaum Quintero has described as “liberal listeners,” who respond to loudness or noise by retreating to private spaces. Instead they became listeners and performers simultaneously as they embraced noise to voice their rage and frustration. Using noise as a form of nonverbal communication is a powerful sonic gesture in a country where symbolic or physical silencing, even as strategic disappearances and illegal executions orchestrated by state actors, have been the standard response of the state to social dissent. In short, noise becomes eloquent when silence symbolizes a necropolitics of social control.

The term eloquence implies both the ability to express ideas and feelings fluently and convince others through language. As a nonverbal means of expression, the potential of noise’s eloquence emerges out of its ability to connect sounding and listening bodies, but also to be analyzed as establishing networks of actors with political consequences. As Leonardo Cardoso has theorized in his study of noise control in São Paolo, noise is relational: it connects the production of social space to tactics of social control and resistance, delineating diverse forms of agency. Cacerolazos invite us to consider how noise’s relational nature not only resides in how we listen to it, but in how we produce it.

In short, noise becomes eloquent when silence symbolizes a necropolitics of social control.

The value of cacerolazos’ noise is its loudness, which serves to simultaneously denounce and challenge the institutional disregard toward the needs and concerns of disgruntled citizens. Banging empty pots also combines sound and visual gestures to recall narratives of scarcity and impoverishment. It suggests that the absence of food, either because is not affordable or because is not available, otherwise renders houseware useless. Therefore, banging pots also expresses the anger produced by the denial and loss of privileges and rights.

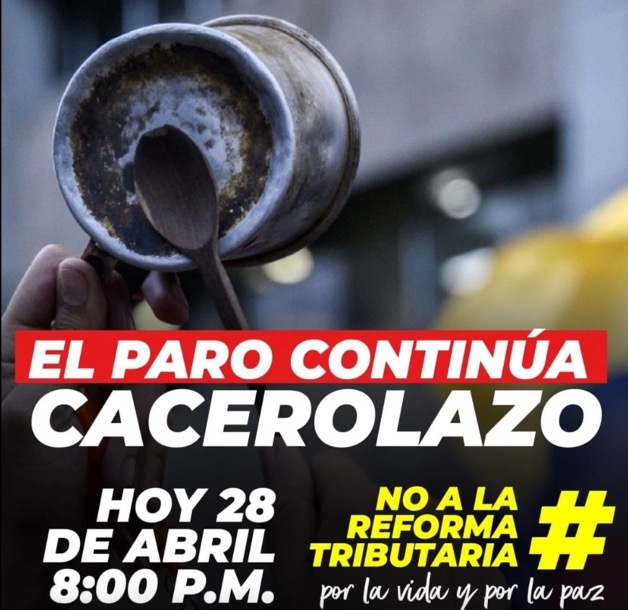

A cacerolazo also resembles an artistic happening in many aspects: both showcase an improvisatory and ephemeral nature, require the audience’s participation, and mix visual gestures and sound. From this standpoint, cacerolazos become theatrical performances of protest that transform kitchen tools associated with private spaces into instruments banged in public. This symbolic transformation has been central to the cacerolazo’s eloquence, since, as suggested above, it blurs of the traditional divide between public and the private spheres and thus calls into question the notion that the state owns public spaces in Colombia. The performative character also makes it possible for people to take to public spaces through sound, even when the state prohibits them from doing so. For example, the 2019 Colombian cacerolazo was the most prominent protest on the streets during curfew. Such performative gestures have also brought a sense of continuity to the social upheaval in Colombia, see the use of the slogan “El paro continúa” (The strike goes on), used in invitations to participate in a cacerolazo, by diverse groups on social media in April 2020.

Screenshot of the invitation to the March 2020 cacerolazo. This time, a new and unpopular tax reform triggered the protest.

Yet, actors enforcing necropolitical silence can harass and target protesters at any time. For example, on May 5, 2021, an unknown gunmen fired at protesters in the city of Pereira. One, Lucas Villa, was shot eight times as he was dancing. He died in the days thereafter. On May 28, 2021, police officers arrested Alvaro Herrera, a young musician, after he participated in Cali’s “cacerolazo sinfónico,” one of the many musicians’ gatherings. Performers organize outdoor concerts inspired by the cacerolazo that have resignified orchestral music-making and musicking within the framework of social dissent. Several NGOs, artistic institutions, and Herrera himself denounced his arrest, and revealed that he was threatened and tortured by law enforcement officers. One day later, a judge ordered Herrera’s release.

The Colombian cacerolazo illustrates how, under particular circumstances, noise’s eloquence allows citizens to denounce and confront a silence that results from the abuse of the state’s monopoly over power and violence. This national context exemplifies how the protests since 2019 have resignified already existing strategic and creative uses of sound, casting a new set of relationships. Citizens become political actors, whether or not they understand themselves as such. The opening words of the first cacerolazo sinfónico at the Parque de Los Hippies in Bogotá on November 27, 2019 suggest as much: “We gathered to show that the arts make it possible to build a violence-free, proactive, and equitable society, where everyone could contribute to nation-building [processes] without a flag or political affiliation.” What can this new set of relationships and experiences of citizenship articulated around sound do? The question remains open. The sonic communities shaped by calcerolazos in Colombia are fragile, and the alliances that constitute them can suddenly change.

About the Roundtable, “Protest in Latin America: 2019 and Beyond”

From Roundtable curator and Musicology Now editorial team member Felipe Ledesma Núñez:

In 2019, waves of mass protests swept the streets of Latin American cities. They were triggered by systemic inequality, corruption, and social injustice, as well as by widespread gendered violence, assassinations of social leaders and activists, and the routine violation of land and environmental rights. Throughout the social movements, sound emerged as a medium to perform and test the limits of citizenship, a means for building networks of solidarity and grassroots organizing, an element of the demarcation of power and territory, a strategic expression of resistance, and a weapon of authoritarian repression. This Roundtable, “Latin America: 2019 and Beyond,“ discusses the sonic expressions of these social movements and their ongoing legacies at local, national, and continent scales. Bringing together Latin American scholars and artists, many contributors to this roundtable will have witnessed the protests firsthand. If you are interested in contributing to the Roundtable, please contact Felipe Ledesma Núñez.

Read the previous post in this roundtable, “Sounding the Path to Dignity: Chile after October 2019,” by Natalia Bieletto-Bueno.